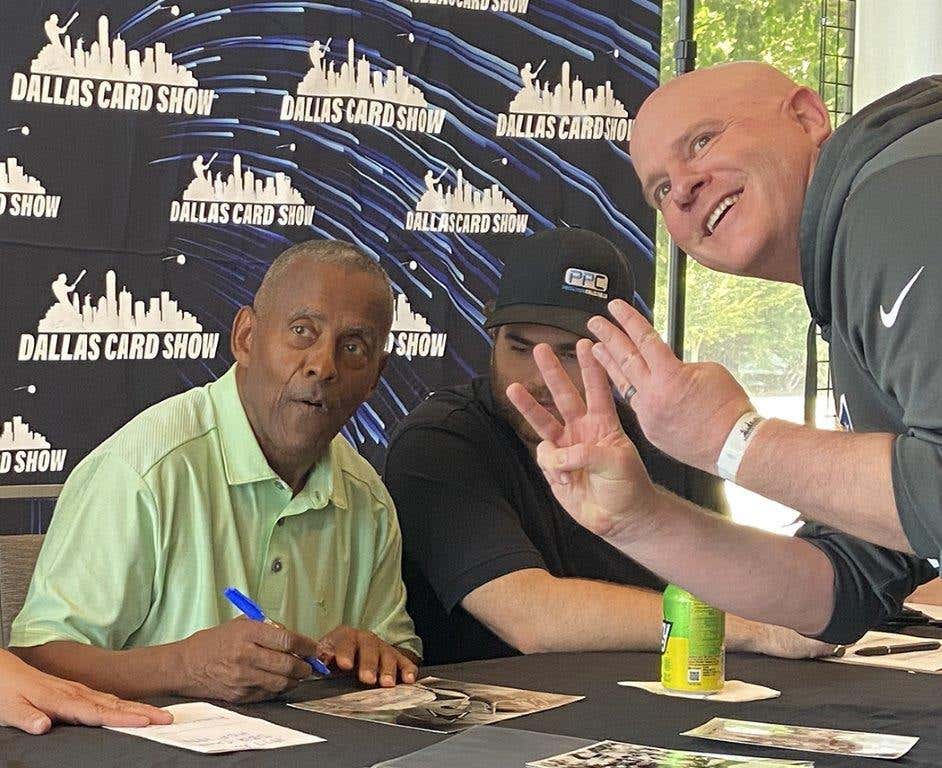

Ted Williams

Edgerton shares Norman Rockwell baseball memories

By Paul Post

With paint brush and easel, Norman Rockwell captured the spirit of baseball in ways ESPN never will.

On Saturday, May 22, 1948, the artist invited his young friend, James “Buddy” Edgerton, to take a trip with him to Boston for a doubleheader the next day between the Cubs and Braves at old Braves Field.

The Saturday Evening Post wanted Rockwell to do a cover showing the Chicago Cubs, which resulted in one of his most famous paintings called “The Dugout.” It shows a sad-looking Cubs batboy standing dejectedly in front of a jeering crowd and a forlorn group of ballplayers in the visitors’ dugout.

“Both the Chicago White Sox and Cubs were hopeless that year,” Edgerton said. “The publisher wanted a picture that showed how terrible they were. It came out in the fall (Sept. 4). That was a pretty quick turnaround.”

Spending time with Rockwell

For Edgerton, a young farm boy, the journey was the experience and opportunity of a lifetime. He lived next door to the Rockwells in rural West Arlington, Vt., which is the subject of the 2009 book he co-authored, “The Unknown Rockwell: A Portrait of Two American Families.” A feature-length film based on it is headed for production.

He’ll never forget going to the ballpark with Rockwell, where the artist needed to get photos to work with. Edgerton describes it in his book.

“I was so excited I could hardly stand it,” he wrote. “It was major league baseball! We got to go to the clubhouse and everyone there treated us like we were celebrities just because we were with Norman. I had just gotten a new Earl Torgeson mitt, ‘The Early of Snohomish,’ first baseman for the Braves, and I got all of the players to autograph it. I used that mitt for years until it was worn out, autographs and all.”

Like Torgeson, Edgerton played first base, for his Arlington High School team in Vermont.

Torgeson, born on Jan. 1, 1924, in Snohomish, Wash., spent 15 years in the majors from 1947-51 with the Braves, Phillies, Tigers, White Sox and Yankees. In the 1948 World Series against Cleveland, Torgeson hit .389 for the Braves (7-for-18) and reached the Fall Classic again 11 years later with the Chisox. In 1950, he led the National League in runs scored with 120.

Attending a Cubs game with Rockwell

Rockwell was all business at the ballpark, before and during the first game. The Saturday Evening Post website says, “Rockwell and a Post art editor strode onto the field and chose people to sit above the Cubs’ dugout. The artist would point to a spectator and contort his face into a gleeful or disgusted look, asking the fan to emulate him, while a photographer snapped them. Later, Rockwell would paint them in. The happy ones were, not surprisingly, Braves fans: the delighted woman to the left was the daughter of a Braves coach and the lady clutching her hands a few faces over was the wife of a Boston pitcher.”

Cubbies depicted in the painting were actual players – left to right, Bob Rush, manager Charlie Grimm, catcher Al Walker and All-Star pitcher Johnny Schmitz.

According to the website jackbales.com, the batboy in the painting was Frank McNulty, a Boston Braves batboy who, like most Rockwell models, was paid $5 for the job, which lasted two to three hours. “After ‘his issue of the magazine was published, he was presented with a Rockwell-signed copy of it during a pre-game ceremony at Braves Field,” the website says. “Not all of the fans shown were actually at Braves Field, for Rockwell routinely used pictures taken in his studio. Ardis Edgerton, the daughter of Rockwell’s next-door neighbors and a frequent Rockwell model, razzes the Cubs through her hands.”

Rockwell quite often included himself in paintings. “The Dugout” is no exception. He’s in the upper left corner.

However, Edgerton didn’t get to see both games, or all of the first one for that matter. Once Rockwell got the photos he needed, they headed back to Vermont where Rockwell began bringing the scene to life on canvas.

Typical of the Cubs, they lost both games.

“On the way back to West Arlington, we listened to the games on the radio,” Edgerton wrote. “The Braves swept the doubleheader, 8-5 and 12-4.”

Growing up next to Rockwell

Edgerton’s love affair with baseball – the Brooklyn Dodgers in particular – began many years earlier, listening to games on the radio in the Rockwell family’s living room.

When Edgerton was about 10 years old, the Rockwells moved next door. Their homes, built in 1810 and 1792, respectively, were only a few feet apart and the neighbors soon became just like family. The oldest of the Rockwells’ three sons, Tommy, was a few years younger than Edgerton.

“I was his big brother while he was growing up,” Edgerton said.

In 1941, Brooklyn and the Yankees began a World Series rivalry that would see them meet six more times over the next 15 years before the Dodgers left New York for Los Angeles after the 1957 season.

“I was always kind of for the underdog,” Edgerton said. “From that point on I was Brooklyn Dodgers all the way.”

One year, when he and Tommy Rockwell were old enough, they ventured to New York on their own and went to a game at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. It was quite an adventure for two small-town kids from rural Vermont.

Edgerton, who played baseball for Arlington High School, tells about the time he and Tommy were hitting pop flies to each other near Rockwell’s studio, when an errant ball sailed through the artist’s pane glass window. It would have cost Edgerton, who was responsible, a small fortune that he never could have paid for.

Rockwell never yelled at the boys. Quietly, he stuck his head out the door and later paid someone to make the repairs.

But the same accident happened again, only a couple of days later. This time, the boys really thought they were in trouble.

However, Rockwell once again never got upset.

“That’s just the way he was,” says Edgerton.

He repeats this phrase quite often about Rockwell to describe how generous, patient and kind he was.

Rockwell's baseball paintings

Rockwell produced several other baseball paintings that fans around the world have come to love such as “Gramps at the Plate,” “The Rookie,” a scene that includes Ted Williams inside the Red Sox clubhouse; and “100th Anniversary of Baseball” that shows a 19th century pitcher winding up, wearing red-and-white striped socks and cap.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown has two Rockwell oil paintings in its collection – “100th Anniversary” and “Three Umpires,” also called “Bottom of the Sixth” and “Game Called Because of Rain.”

“The art of Norman Rockwell captures the heart of America, and the game of baseball has lived within that heart for more than 150 years,” said Craig Muder, Hall of Fame spokesman. “Rockwell’s pieces are among the must-see artwork in the museum’s impressive collection. They continue to enthrall visitors of all ages.”

Edgerton, 86, who now lives in South Burlington, Vt., said “The Umpires” is his favorite Rockwell baseball painting. The Saturday Evening Post published it on April 23, 1949.

“I have a copy of it hanging right here on the wall,” he said. “It tells a great story. It tells about the Brooklyn Dodgers, too.”

The scoreboard shows Brooklyn losing, 1-0, and Dodgers coach Clyde Sukeforth trying to convince Pittsburgh manager Bill Meyer that the game shouldn’t be called because of rain, which would result in a Dodger loss.

The scoreboard also shows the Brooklyn lineup, with No. 42 – Jackie Robinson – hitting second and playing second base.

Edgerton credits Rockwell and his wife, Mary, for having a major influence on his life. Aside from being extremely close friends, they encouraged him to attend college, which no one in his family had ever done before.

Edgerton went to the University of Vermont, had a long successful career as a county farm agent and is now a UVM professor emeritus.

Each spring, his thoughts turn back to baseball. However, he’s now more of a Red Sox fan since the Dodgers left New York.

But he hasn’t stopped rooting for the underdog. Edgerton said he’d like to see the Cubs, which haven’t won a World Series since 1908, go all the way this year.

“They’ve been beat on too long,” he said.