Collecting 101

The Great Roger Maris Old-Timers’ Bats Experiment

Les Lieber is a man who knows a good idea when he hears one. Or when he comes up with one himself. And he came up with a doozy in the spring of 1962. In a time when daily newspapers boasted a clout and a demographic reach that would be almost impossible for Generation X’ers to fathom, Lieber was what was called a “Roving Editor” for This Week Magazine.

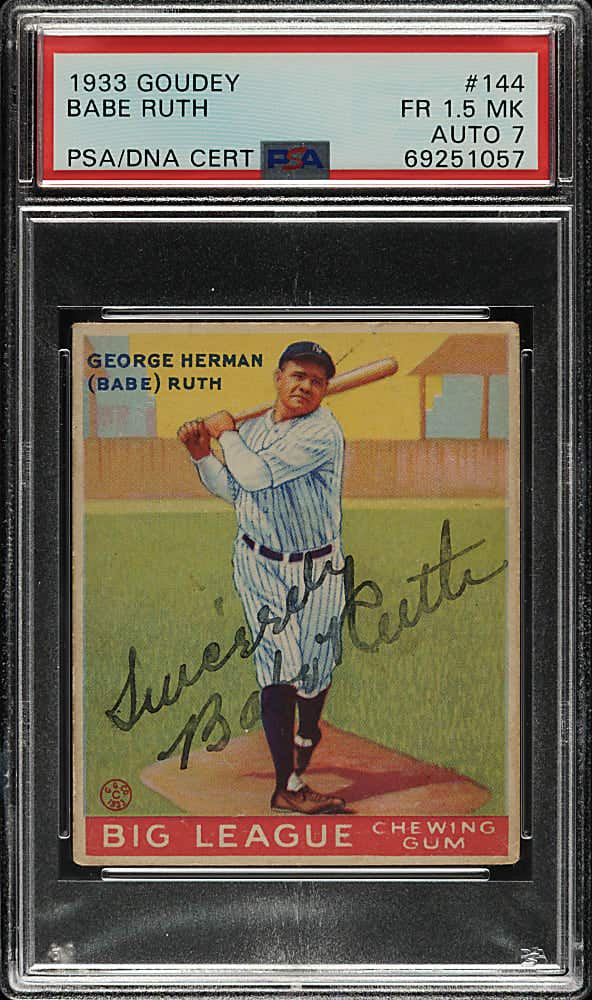

A lifelong baseball fan, the New York native was as enthralled as the rest of the country in 1961 as Roger Maris chased the hallowed single-season home run record that had been held for more than three decades by Babe Ruth. And the debate that ensued about the circumstances surrounding that historic chase included a good deal of speculation about the new, lighter bats.

At spring training in Fort Lauderdale, the enterprising Lieber decided to stage an elaborate experiment to test the impact of the modern-style bat. The keys to his grand investigation: Roger Maris (and his own bat), four custom-made bats from famed batmaker Hillerich & Bradsby and a 100-foot tape measure that Lieber would use to track how the new home run champion did with lumber that precisely matched the specifications from the bats used by four of the game’s all-time greats. So the good folks in Louisville, Ky., crafted bats that were exact models of those used by Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Frank “Home Run” Baker and Pete Browning. A fifth bat used in the “experiment,” a Roger Maris model, was supplied by the slugger himself.

More than 40 years after the article was published, the four bats have surfaced as one of the coolest auction lots to come down the pike in some time. It should come as no surprise that Pete Siegel, he of considerable fame as the president of Gotta Have it Collectibles in Midtown Manhattan, would be the man behind the unusual single-lot auction that figures to attract a lot of media attention well beyond the traditional hobby channels.

It’s one of those odd situations where the results of the “experiment” are infinitely less important than the emergence of the four bats in the hobby. The expected mainstream media interest is likely to be nothing short of sensational for a group of artifacts that boasts the remarkable provenance of a magazine article featured in 40 newspapers with a total circulation approaching 14 million readers. And it was featured on the cover of the magazine as well, with a classic image of Maris in his home run swing, with the title “Roger Maris Homers With Ty Cobb’s Bat.”

Whoops, I may have given a bit away about the results of Lieber’s experiment, though as noted above, the results aren’t terribly compelling relative to the event itself.

Lieber, who produced more than 500 articles for This Week Magazine between 1946-70 before it, in his own words, “succumbed to television,” is 93 now and living in New York City with his second wife. I was fortunate to be able to interview him for more than an hour as he talked about the bats, the magazine that made the bats so special and the process that led to him seeking out Siegel in the first place.

* * * * “I came from a baseball family in St. Louis,” he told me when I asked about the genesis of the bat story. He was a St. Louis Browns fan, and by his own account kept that interest alive all his life, the interest in baseball that is, since the Brownies left St. Louis in 1953.

In his quest for stories for the magazine, he would go to Florida in the 1950s and 1960s for spring training, golf and fishing. This was a time when newspapers ruled the media world, and the search for the offbeat angle was a never-ending process for “roving” freelancers like Lieber.

That quest for unusual angles even sent him to Paris, France, to take a tongue-in-cheek look at French baseball for the magazine. “They didn’t understand baseball at all, which is funny,” Lieber recalled. “When they saw a right-handed batter run to first base, they figured a left-handed batter would run toward third.”

The genesis of the Maris feature was a bit more straightforward, given a boost by an earlier This Week Magazine story Lieber had done with Joe DiMaggio. As Lieber recounted in the bats story, The Yankee Clipper had attributed the home run rampage to the whiplash effect of the modern light, tapered bats.

“The year that Maris hit 61, there was a lot of talk about the bats being lighter,” Lieber said, along with rumblings about a doctored baseball as well. “I decided to try to settle the issue.”

After deciding to include bats from Ruth, Cobb, Baker and Browning, Lieber was left with the challenge of getting the bats built. To that end, he had more than a leg up: he had done a major feature on the Kentucky batmaker for the magazine more than a decade earlier. Lieber noted that Hillerich & Bradsby officials were pleased with the article, so getting the four bats made was no problem, once the specifications were dusted off from the archives. The four bats were promptly shipped to the Yankees in spring training in Florida.

I should let the the master storyteller take over at this point, as recorded in the 1962 story: “The Yankees let us use their field and contributed 30 baseballs (five extra in case of out-of-the-park fouls), plus the services of their distinguished veteran coach, Frank Crosetti. Frankie volunteered to stand beyond the right-field fence and mark the exact spot of any Maris home runs.”

With Crosetti helping out, Lieber scrambled around planting slips of paper with the names of the four old-timers at the various spots where the flyballs landed. “I got more exercise than anybody,” Lieber said with a laugh, adding his own disbelief about the bat that came in last place. “I think Maris did the worst with his own bat,” he recalled, an observation borne out by by results listed in the adjacent article, but as mentioned earlier, the results aren’t nearly as important as the emergence of the bats in the hobby. And not surprisingly, that’s another story.

When Lieber’s oldest son, David, was leaving for a new job in Munich, Germany, 17 years ago, his father wanted to give him something special to take with him to his new home overseas. “So I gave him the four bats,” said Lieber, who had stored them away in a locker for all those years.

David wanted the Ruth and Cobb bats, but ultimately suggested that he give the other two, Browning and Baker, to his younger brother, Jon. Thus, the Ruth and Cobb bats have resided in Germany since 1988, presumably in a well-protected location.

Once Lieber decided to put the bats into the Gotta Have It auction, he was faced with the challenge of convincing his sons that it was the right way to go. David initially had his doubts about the idea. “At first, David wasn’t too anxious to sell them,” Lieber recalled, adding that his Jon wasn’t too happy about the decision either.

Both eventually came around.

* * * * Tales of Ted, Yogi and Sam Snead

I talked to Lieber for more than an hour, but I suspect one would need much more than that to do him justice. You would suppose that having a resume of 500 articles or so in a nationally circulated magazine would wind up being the first line in his curriculum vitae, but apparently not so with Lieber. Seems he’s also a jazz musician of national renown, having played the alto sax and pennywhistle with the likes of Benny Goodman and a host of other jazz greats.

I even googled him (I hope readers are impressed that I used “google” as a verb), and turned up hundreds of entries related to his efforts promoting jazz in New York City and nationally, but at least for purposed of this article, his literary efforts remain the focus.

Younger readers might not “get it,” as they say, but the offbeat article ruled the magazine world for many years, back in a time before every conceivable little pocket of interest had its own magazine(s).

Newsstands touted only a tiny fraction of the number of different titles that might be available today, and “roving editors” like Lieber were expected to find fresh, new angles for virtually every story idea.

“Golf is one of my main interests, even more than baseball,” Lieber said in recalling some of the unusual golf stories he did for This Week Magazine.

Lieber used to visit the Boca Raton Country Club where Sam Snead resided as club pro, and even pitched an idea that Snead, renowned as a fast player, would play 18 holes going from shot to shot in a helicopter, with the writer along to record the quirky event.

That idea got nixed, but he did manage to sell his bosses on another bit of Snead mischief. The legendary golfer had boasted for years that – using only a branch from a tree – he could beat anybody in the club. Lieber volunteered for the duty, then proudly wrote the article “How I Beat Sam Snead,” for the magazine. “That’s the kind of story I liked to do,” he told me.

Still, baseball ruled the magazine world in those days, so Lieber came up with nifty bylined pieces from the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Yogi Berra, among others.

“There’s No Place Like Homeplate,” provided Yogi with an opportunity to reveal the inside dope about what goes between the catcher, batters and umpires, the kind of Berra musings that helped to advance the legend of his comically fractured syntax. Lieber added that much of the best stuff in the piece ostensibly from Berra actually came from the Hall of Fame catcher’s lifelong friend, Joe Garagiola.

That’s hardly news to serious baseball fans, but Lieber did pull off one of many scoops with three different stories from Ted Williams at a time when Williams wasn’t doing much talking to the sportswriters.

Lieber recalled a time at spring training when Teddy Ballgame invited him to jump in the car and head back to Ted’s apartment for an interview. Williams liked milkshakes, so they wound up at a drugstore near Ted’s apartment.

“I told him I was a jazz musician,” Lieber said, adding that they quickly hit it off as Errol Gardner fans (“Misty”). With rapport established, Lieber started asking Williams about his legendary beef with the sportswriters, and to Lieber’s amazement, the slugger was receptive to the idea of doing a story about it. He called his bosses back in New York and somehow wrangled a $2,500 fee for Williams, a huge sum in the 1950s and certainly even more impressive when you consider that it wasn’t customary to provide fees for interview subjects.

They began to talk and Williams told him that he didn’t really have any animosity toward fans as some of the writers suggested at the time.

Williams ultimately liked the story that Lieber did, and granted another interview a few years later when he told about a fan who’s reportedly credited with helping to bring the Splendid Splinter back for one more year on the field in 1960.

“A man with a briefcase approached Williams at the Baltimore train station in 1959,” Lieber recounted, and asked him, ‘Is it true you’re going to retire next year?’ And then the man explained to Williams about all the all-time records and milestones that Williams was approaching.”

According to Lieber’s article, the fan, who lived in Pennsylvania, kept sending Williams telegrams as he passed different records over the rest of the year and into 1960, Williams’ final campaign.

It’s stories like those that have Lieber thinking about doing a book, an idea that got a major boost after he started looking through his clips in search of the Maris bat piece. “I did more than 500 articles from 1946-70, stories that I think paint a picture of the century,” he said.

Sounds like a winner to me. I’m still trying to dig up that piece about Sammy Snead playing golf with a tree branch. Now that’s my idea of offbeat. Plus, I still use a pitching wedge that’s almost as old as Lieber. Got it from a grandfather I never knew.

And the Winner is ...

The long-forgotten batting experiment, which took place during spring training in 1962, followed the historic chase of Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record that prompted a controversy over bat weight vs. distance. Maris established the new record with 61 home runs using a bat that was 11 ounces lighter than Ruth’s.

Freelance sportswriter Leslie Lieber, on assignment for This Week Magazine, persuaded Maris to test the theory that the old, heavier bats used by some of baseball’s all-time greats would have been more difficult to hit home runs with than the modern, lighter bats. As a side note, Mark McGwire used a 35-ounce bat to hit his 70 home runs in 1998, and Barry Bonds used a 32-ounce bat to hit his 73 home runs in 2001.

Working in cooperation with the New York Yankees, (for use of Ft. Lauderdale Stadium) and legendary Yankees coach Frank Crosetti, Lieber, put his “experiment” into motion. With Crosetti measuring home run distances outside the right-field fence and Lieber doing the “in-park” measurements with a 100-foot tape measure, Maris used each bat to propel five fly balls.

The Cobb bat (42 ounces, 341/2 inches) measured 1,621 feet, the best mark of the group. The Baker bat (47 ounces, 34 inches), was second, Browning’s third (46 ounces, 37 inches), Ruth’s fourth (44 ounces, 35 inches), and Maris’ own bat, fifth and last (33 ounces, 35 inches).