Willie Mays

Led by the ‘Big Three,’ popular 1954 Topps Baseball set tells story of historic, glorious season

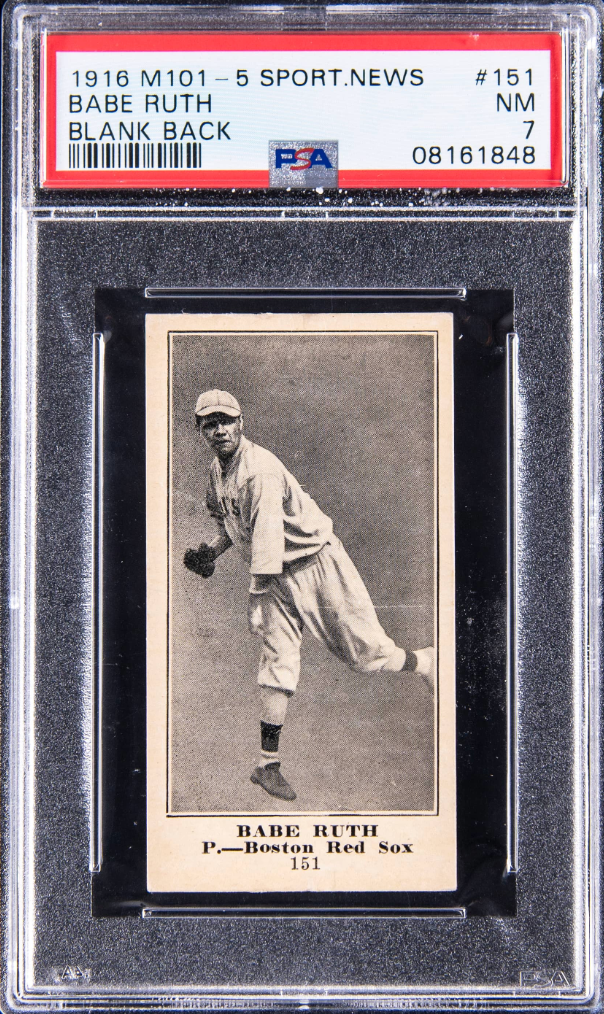

When sports card collectors are asked to name their favorite sets of the past, the 1954 Topps Baseball set, issued in the middle of the “card wars” with rival Bowman, is usually in the top 10 but never the top two or three.

Few have anything negative to say about the set but even fewer place it in the pantheon of the very best. All agree, however, that the set is clearly superior to Bowman's 1954 set. The Topps set has some universally acknowledged assets, especially the “Big Three” (or “Big Four”) rookie crop and seems to contain something for everyone, in spite of a few noticeable negatives.

The most obvious positive feature is the set’s sheer physical presentation. The card fronts are extremely attractive. The layout of a vertical full-color, close-up portrait of the player with a smaller black-and-white full-figure action shot is eye-catching, so much so that Topps repeated the format in 1955 and 1956, modifying it only by rotating the basic layout from vertical to horizontal and making all shots color. In some cases Topps went so far as to reuse the 1954 head shot. The 1955 set even continued the blank background, although Topps replaced this with a stadium scene for its 1956 set. Also included is the player's autograph at the bottom of the card and his name, position, team and a large team logo at the top. All this is set against a solid background of various colors.

The cards were printed head-to-head, with each card abutted against another with a shared background. This meant each card's white border extended only to the sides and bottom of the card. This also allowed later collectors to reconstruct at least a partial layout of the sheet upon which they were printed. For example, I have a card of Pirates second baseman Curt Roberts (card #242) that is miscut top to bottom so that it can be aligned perfectly front and back only with that of Red Sox coach Carl Schreiber (#217).

With card fronts facing each other as in a mirror, card backs ended up the same way. Thus, when Topps' printing presses ran one-third white, or off-white, and two-thirds green printing from edge to edge with no borders over the backs of the adjoining cards of Curt Roberts and Carl Schreiber, backs were aligned with each other but reversed when the two card fronts were placed next to each other. So the collector who places his 1954 set in an album finds that the card fronts all look fine but half of the backs are upside down.

The backs of the 1954 cards are just as eye-catching. In the light portion which makes up the top third of the back is the player's complete legal name. The All-Star Yankee catcher may be “Yogi” on the front of his card (#50), but he is “Lawrence Peter Berra” on the back. And White Sox pitcher Mike Fornieles (#195) becomes Miguel Fornieles y Torres on his card back, although his full name was actually Jose Miguel Fornieles y Torres.

The lighter background also contains the card number inside a baseball and the player's physical statistics. Finally, the player's professional biography is written up in some detail. Unfortunately, in most cases, this paragraph provides nothing more than a straightforward summary of the player's career and any military service and (at best) a highlight or two. A few include the player's nickname. For example, Cardinal pitcher Wilmer “Vinegar Bend” Mizell (#249) is “nicknamed for his hometown in Alabama.” And Hall of Fame Yankee shortstop Phil Rizzuto (#17) is “called 'Scooter' because of the ground he covers.”

The lower two-thirds of each card contains two features against the green background. One is the expected two lines of past major or minor league performance, labeled “Year” and “Life.” The second feature more than makes up for the lack of unusual background in the biographical section. This is the “Inside Baseball” cartoon strip at the card's bottom. The title of the strip is misleading because the cartoons do not reveal any tips on baseball strategy or significant historical facts but rather some unusual occurrence in that player's life or career.

Some are amusing. We are told infielder Bobby Adams (#123) is valuable to the Reds in more ways than one. “Aside from being a top Cincy player on the field, Bob helped them last winter. He became a ticket seller during the off season and is now recognized as the Reds' top salesman.”

When a Dodger batter ran out to the mound to fight Paul Minner (#28), “the powerful Cub hurler didn't start swinging but walked away! Paul could take care of himself! He was more interested in taking care of his new $250 set of teeth!”

Athletics catcher Jim Robertson (#149) “is a tumbling instructor and can toss off a neat cartwheel or backflip!” And third baseman Andy Carey (#105) is the biggest eater on the Yankees, “a leader at the PLATE both on and off the diamond.”

Some are startling. Red Sox infielder Billy Consolo (#195) “at the age of 13 played in the California Winter League, which had major league stars!”

Pirate shortstop Dick Groat (#43) “was an All American basketball player at Duke. He couldn't decide whether he wanted to play pro baseball or basketball. So ... In '52 he did both!”

THE BIG 3 (OR 4)

One noticeable casualty from the card wars is the reduced number of cards in the set. Topps went from 407 cards in its landmark 1952 set to 274 in the popular 1953 set, and then further to only 250 in 1954 (on its way to a mere 206 in 1955). This was obviously due to the loss of players to Bowman, as both companies sought to bind players exclusively to their products.

Conversely, there were a number of obvious exceptions with players, both stars and journeymen, who appeared in both the 1954 Topps and Bowman issues. One is Willie Mays, who is #90 in the Topps set and #89 in the Bowman set.

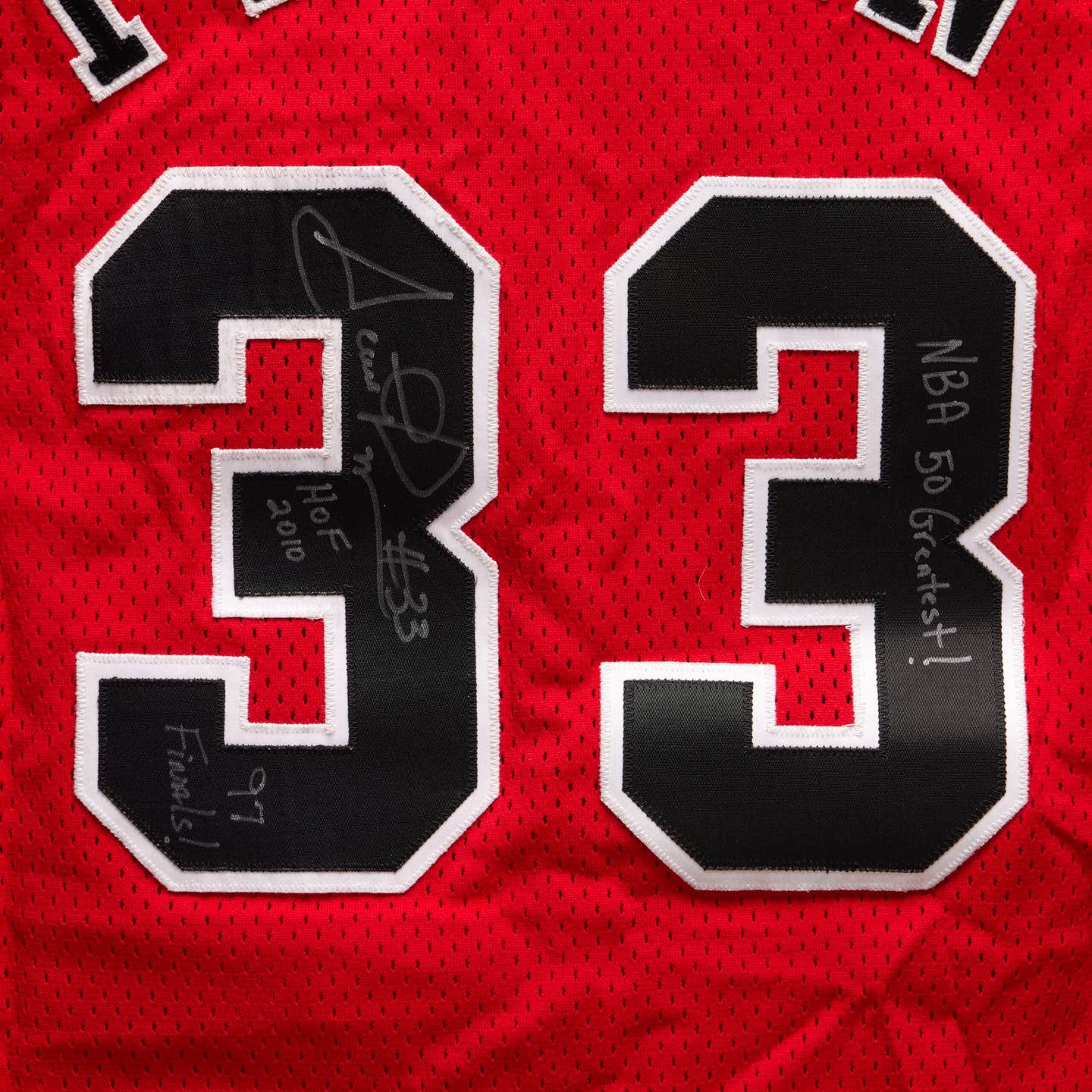

The first thing collectors mention when they discuss the 1954 Topps set is the presence of the “Big Three,” which is sometimes expanded to the “Big Four.” This refers, of course, to the rookie cards of Henry Aaron (#128), Ernie Banks (#94) and Al Kaline (#201). The collector who seeks to complete this set should expect to pay for these three cards around the same amount as the other 247 cards combined.

At the top of the list is the Aaron rookie, now averaging about $5,000 in very good condition and well into six figures for Near Mint. The Banks card typically sells for about half of that, while the Kaline card is worth about half of the Banks. All three appear only in the 1954 Topps set. The Bowman set contains no rookie cards worth anywhere near the prices of the “Big Three,” with its most prominent rookies being Harvey Kuenn, Don Larsen, and 1950-60s slugger Frank Thomas.

Sometimes included with these three ultra-popular cards is a fourth rookie, Brooklyn Dodgers left-handed pitcher Tom Lasorda (#132). It is mostly forgotten now but the Hall of Fame manager pitched four games for the Dodgers in both 1954 and 1955. After a brief stint with the Kansas City A’s in 1956, he retired with a career record of 0-4, only to return two decades later for a long, successful managerial career that landed him in Cooperstown.

But Topps included him as a player in 1954 so his rookie card can be found alongside Aaron, Kaline and Banks in this epic set. Although the Lasorda card is sometimes listed as one of the hot rookies of 1954, his card sells for only a fraction of the “Big Three.”

HALL OF FAMERS

The set is loaded with Hall of Famers. Topps evidently wanted to herald its exclusive contract with Ted Williams, recently returned from combat missions in Korea. It did so by featuring his picture on its wax boxes (but strangely not on either the 1-cent or 5-cent packs found in the boxes).

It also honored Williams by opening and closing the set with him. So you can find Ted Williams twice in the set, as cards #1 and #250.

Among the numerous other Hall of Famers are Jackie Robinson (#10), Warren Spahn (#20), Duke Snider (#32) and Whitey Ford (#37).

Topps enjoyed no monopoly, however. The only nationally distributed card of Mickey Mantle can be found in the 1954 Bowman set. Other stars found only in Bowman packs include Roy Campanella, Robin Roberts, Bob Feller and Pee Wee Reese.

Mays is the most prominent, but not the only, player whose card is available from both companies. Some players like Mays apparently did not sign exclusive agreements with either company and are found in both sets, such as Rizzuto and fellow Hall of Famers Richie Ashburn and Hoyt Wilhelm. Not all such dual issuances were stars. Minor stars like Don Mueller and common players like Dick Kokos made it into both 1954 sets.

One somewhat unusual entry in this category is Williams. In its initial printings Bowman included Ted Williams as card #66. After the threat of legal action from Topps, Bowman withdrew his card and substituted a new #66 picturing Williams’ fellow Red Sox outfielder Jimmy Piersall, which is basically a reprint of his original card #210 with only the number changed. So the 1954 Bowman set can be found with two different cards numbered #66, with the Williams card being noticeably more scarce and considerably more expensive.

MANAGER CARDS

With so many players joining Bowman's ranks, Topps was forced to look elsewhere for faces and names to put on cards in its later series. The great majority of the set's stars are found in the lower numbers, especially in the first 50 cards. Topps was then forced to fill in the higher number series with more than two dozen cards of managers and coaches.

Most of the smaller full-figure photos of these men are current shots of them as middle-aged or older on the sidelines, including Pirates coach John Fitzpatrick (#213) who seems to be adjusting his pants. However, in a few cases, the action shot shows them decades earlier as active players, such as the great shot of Tigers pitching coach Lynwood “Schoolboy” Rowe (#197) as a young flamethrower.

The good news is that such manager and coach cards present an opportunity to acquire cards of earlier greats for prices significantly less than cards issued of them as players in their prime. For example, a 1954 Topps card #183 of Hall of Famer Earle Combs, then coaching for the Phillies, will cost a fraction of his 1933 Goudey or another card from his career as an outfielder for the legendary Yankee teams of the 1920s and 1930s.

The same goes for the other two Hall of Famers found in the set as coaches, Billy Herman (#86) and Heinie Manush (#187). The bad news is that, other than those three, the other coaches were mostly “common” as players and even more common as coaches. A prime example is Braves bullpen coach Bob Keely (#176), whose major league career consisted of two games and one at-bat.

The manager cards are even more disappointing. In contrast to 22 coaches, there are only four managers in the set. Three are Eddie Stanky (#38), Fred Haney (#75) and Steve O'Neill (#127). The fourth is Phil Cavarretta (#55), who was in the Topps set as a Cubs player/manager but not in the Wrigley Field dugout in 1954 after being fired by the team prior to the season.

Incredibly, none of the six future Hall of Famers serving as managers that year (Walter Alston, Lou Boudreau, Leo Durocher, Bucky Harris, Al Lopez or Casey Stengel) can be found in the set.

Also appearing in the higher numbers are several players who appeared in the majors only briefly in 1953 and several others, similar to Lasorda, who were merely prospects. One was Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Leroy Wheat (#244), whose career consisted of 11 games and a 0-2 record. According to Topps, 18-year-old Yankee first baseman Frank Leja (#175) was “likened by Yankee scouts to the immortal Lou Gehrig,” but managed only one hit in 23 career at-bats.

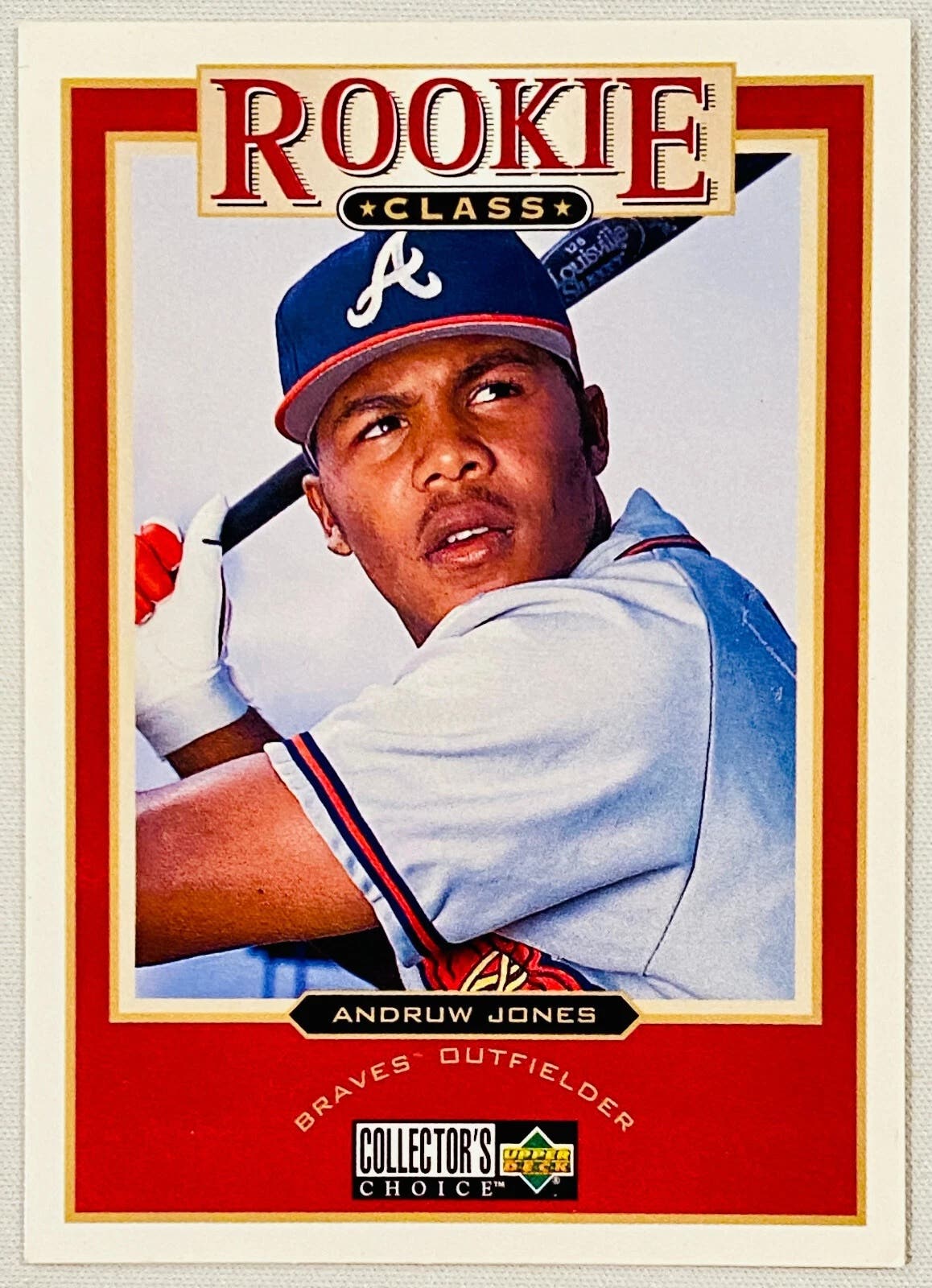

Besides Hall of Famers, the set contains a number of players whose cards are priced as commons today but who enjoyed at least one moment of fame. Topps' first ever multi-player card is found in the set. Card #139 shows identical twins Ed and John O'Brien, shortstop and second baseman, respectively, of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Both were also basketball stars at Seattle University and were drafted by the Milwaukee (now Atlanta) Hawks of the NBA but opted for baseball, continuing as Pirate teammates until 1958, when John was traded to the Cardinals and Ed was sent to the minors. Their card states that they are the first set of twins to be big-league teammates. However, a baseball historian later discovered that twins Joe and Red Shannon preceded them by playing together in one game for the 1915 Boston Braves.

Also found in the set is Giants outfielder Jim “Dusty” Rhodes (#170), who would go on to win MVP of the 1954 World Series. Card #16 shows Pirate backup catcher Vic Janowicz, who won the Heisman Trophy in 1950 and who played (with more success) in the NFL in the offseason.

Card #77 shows Tigers third baseman Ray Boone, father of Bob and grandfather of Bret and Aaron, all major leaguers. Neither card mentions it, but Athletics pitcher Bob Cain (#61) and Tigers coach Bob Swift (#65) were the Detroit battery in St. Louis on Aug. 19, 1951 when a 3-foot-7 midget Eddie Gaedel, wearing number 1/8, had his one career at-bat for the Browns.

The 1954 set is the last to picture the Philadelphia Athletics, who moved to Kansas City in early 1955. It is also the first to picture the Baltimore Orioles, who not only relocated from St. Louis but also dropped the former Browns name and, a dozen years later in 1966, captured the franchise's first championship.

The Browns' move to Baltimore created an interesting dilemma for artists at Topps (and Bowman also). When designing the cards in early 1954, they had no idea what the new team's uniforms would look like. This was no problem for the small full-figure shots, where shirt fronts and hats are blank (almost certainly airbrushed out) or not readable. But for the large head shots of players Topps chose to add a colorful bird, obviously an oriole, to each cap. The problem is evident when Topps cards of Baltimore players are compared, for no two birds on the caps are exactly alike.

ERRORS

The 1954 Topps set is known to contain more than a few errors, none of which were corrected. The autograph of New York Giants pitcher Ruben Gomez (#220) includes a “C” after his name resulting from Topps cutting off most of his full last name of “Colon.”

Erroneous dates of birth are given for several players, including Williams (#1) and Hoyt Wilhelm (#36). Bill Glynn's last name is misspelled “Gylnn” on the front of his card (#178).

These pale in comparison to the 1954 Bowman set, which has (at last count) 40 variations resulting from corrections to initial errors, not to mention numerous uncorrected ones, most notably showing Willie Mays' last name as “May” on his card front.

It has been accepted since 1954 that the Topps set was issued in three series. The most common is the first series of 50, which luckily for collectors includes the majority of the set's Hall of Famers.

Slightly less common is the third series of 175 cards numbered #76 to #250. Commons in these two series now book for about $15 in VG condition, with Hall of Famers averaging about $30, excluding Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays at $600 each.

Somewhat more difficult to find is the second series of 25 cards numbered from #51 to #75, costing about $20 in VG condition, with Larry Doby (#70) being the sole Hall of Famer.

Unfortunately, not one uncut sheet of any of the series is known to exist today, so questions remain about the set's distribution. Most sources state flatly that the 1954 set was printed on sheets of 100 cards each. If so, the first sheet contained two copies of each of the first 50 cards and the second contained four copies of cards #51-75.

So why is the second series not twice as plentiful as the first? Also, how were the final 175 cards printed on sheets of 100? Were they printed on two sheets of 100 cards each, resulting in 25 cards in the last series being double printed?

Were they printed on seven sheets of 25 cards, with each card appearing four times? If so, were any sheets printed in greater quantities than others, making some of these seven series more abundant?

Further, the 100-card sheet is itself not a certainty. Topps 1955 baseball and football cards, despite being the exact same size as 1954 baseball, are generally held to have been printed not on sheets of 100, but on sheets of 110. So the 100-card sheet of 1954 is at least open to question.

If the 1954 set was, in fact, printed on sheets of 110, there is additional likelihood of some double prints, whether the sheets contained 25, 50 or 100 different cards.

A WRAP

The 1954 baseball season was historic and is noteworthy 70 years later, and not just because of the movement of franchises. “The Big Three” began their magnificent careers. Other young players like Mays, Mantle and Whitey Ford really came into their own.

The Cleveland Indians ended the Yankees’ streak of five straight American League pennants, winning a record 111 games, only to be swept in the World Series by the New York Giants, highlighted by Mays’ spectacular catch of a Vic Wertz drive in Game 1 that is still broadcast today.

Williams and other players were back from the Korean War. And the Topps set of 1954 captured all of this in such glorious detail that the set remains a popular classic today.