News

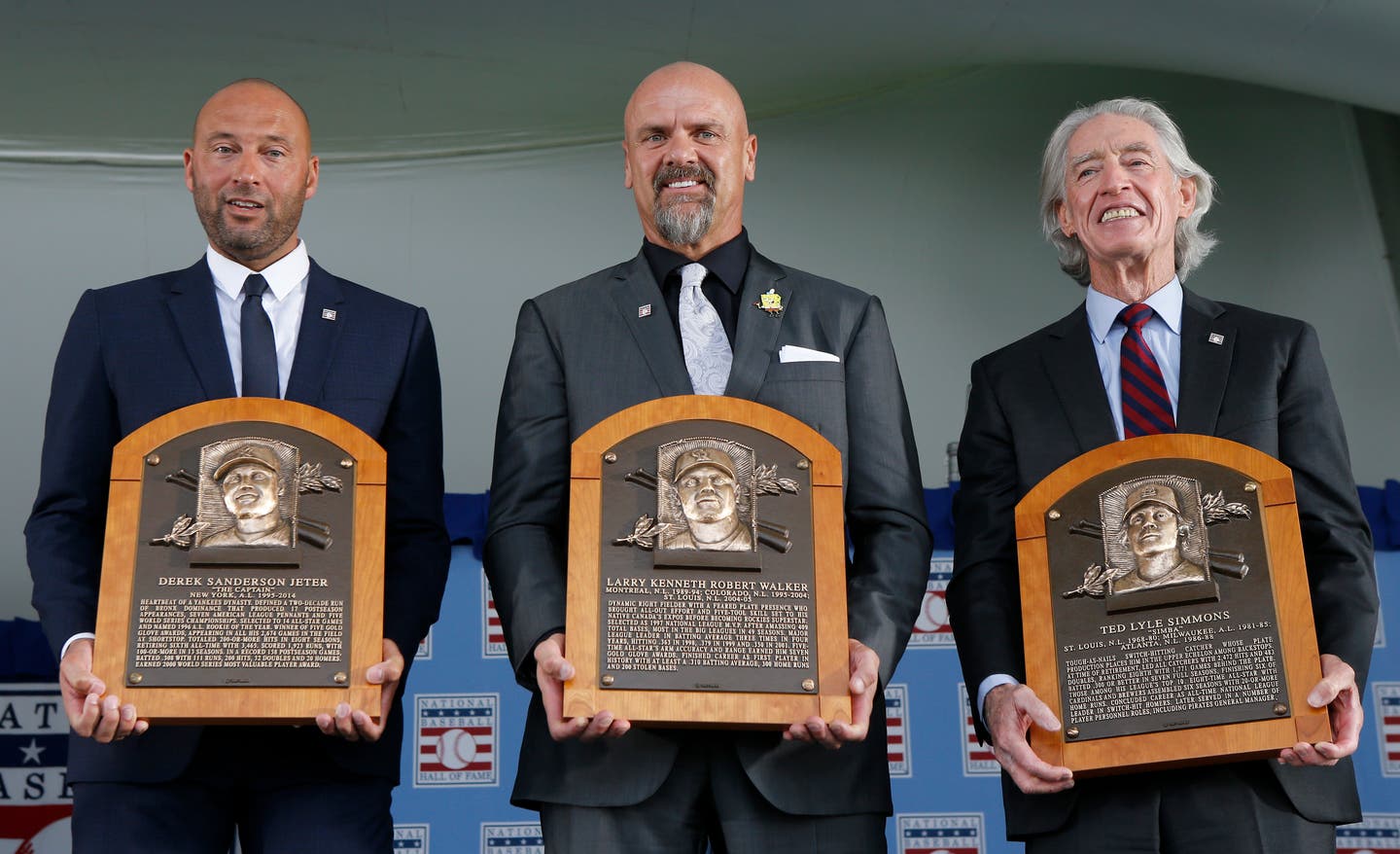

For Derek Jeter, Larry Walker and Ted Simmons, Hall of Fame induction was worth the wait

Good things come to those who wait … and wait … and then wait a little longer.

That was certainly the case for the Baseball Hall of Fame class of 2020, whose induction ceremony was finally held on Sept. 8, 2021. That ceremony, originally scheduled for July 26, 2020, was postponed for more than a year after Covid-19 gripped the nation.

The Sept. 8 crowd, estimated at 20,000, was a sea of Yankee pinstripes as many attending the ceremony wore a number 2 Yankees jersey to honor New York shortstop Derek Jeter, one of the inductees. The maple leaf was also strongly evident as fans came from north of the border to salute another one of the inductees, Canadian outfielder Larry Walker.

Despite vaccines slowing the spread of the virus, the threat of Covid variants had everybody at the Hall of Fame holding their collective breath as the event neared in early September. Even Jeter — Captain Clutch himself — was hoping Lady Luck would come up big for him and his fellow inductees and let the festivities proceed without a hitch.

“I don’t want to jinx anything. I’m knocking on wood,” the former Yankees shortstop said when asked a week before the ceremony if he was excited about finally being officially inducted. “I’m looking forward to getting up there. It’s been a long time coming.”

It certainly has.

Jeter and Walker were elected to the Cooperstown shrine by the Baseball Writers of America Association (BBWAA) on Jan. 21, 2020 — more than a year and a half earlier. They joined veteran catcher Ted Simmons and the late union leader Marvin Miller, former executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, who had already been elected to the class of 2020 by the Hall of Fame’s Modern Baseball Era Committee. No one was elected to the Hall of Fame by either the BBWAA or the veterans’ committee in 2021.

The July 2020 induction ceremony for Jeter, Walker, Simmons and Miller had to be shelved because of the pandemic. That meant that the Hall of Fame plaques honoring all four men would not take their rightful place in the Hall’s sacred Plaque Gallery until an official induction ceremony could be held. That finally came on Sept. 8.

Since 1979, the Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony has been held on a weekend, with a full schedule of events for fans and Hall of Famers alike. The pandemic forced a scaled-back schedule on a weekday to keep everybody safe.

Some annual favorite induction-related events had to be canceled, like the Parade of Legends down Main Street in Cooperstown. However, the actual induction ceremony was no less dramatic.

Retired Yankees center fielder and Jeter teammate Bernie Williams, a jazz guitarist, performed the national anthem as an instrumental. Williams did the same musical honors at the 2019 induction event, when another former teammate, Yankees star closer Mariano Rivera, was inducted.

The crowd came to pay tribute to Jeter, Walker, Simmons, and Miller. Thirty-one legends of the game, all members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, sat on the stage as the ceremony took place. And when it was over, the plaques unveiled, the pictures taken, the memories of the exploits of these great inductees still fresh in the minds of all those who attended the event, it was as if Major League Baseball had just gotten a walk-off win against Covid-19.

Jeter’s induction had been greatly anticipated ever since he retired from baseball in 2014 after 20 seasons with the Yankees. A player has to wait five years before becoming eligible to be voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Jeter, now 47, had an outstanding career with the Yankees from 1995 to 2014. His career 3,465 hits, 1,311 RBI, 260 home runs and .310 batting average put him among baseball’s elite. Still, the 14-time All-Star always insisted that getting into the Hall of Fame was not a sure thing.

“Everyone told me it [getting into Cooperstown] was a foregone conclusion, but I didn’t buy it,” Jeter recalled. “There was a lot of anxiety. I was nervous sitting around, waiting for a phone call about something that was completely out of my control.”

But Jeter did get that call on Jan. 21, 2020. So did outfielder Larry Walker, who played 17 seasons in the bigs (1989–2005) for three teams — the Montreal Expos (1989–1994), the Colorado Rockies (1995–2004) and the St. Louis Cardinals (2004–2005). Walker knows a thing or two about waiting.

The BBWAA didn’t elect Walker, a lifetime .313 hitter, until his 10th and final year on the ballot.

“No worries,” he said. “I waited 10 years. What’s one more?”

A YANKEE LEGEND

As with all Hall of Fame inductions, the memories flowed as the ceremony proceeded. Jeter reminisced about wanting to play shortstop for the Yankees as a youngster.

“I first fell in love with playing shortstop because my dad was a shortstop,” said Jeter, whose father, Charles, played shortstop for Fisk University in Nashville. “I wanted to be just like him.”

A five-time Gold Glove winner, Jeter recalled that after his playing days, his father came over to him and said, “I played every game with you.”

The former Yankees star gratefully acknowledged the support he received from his family, including: his father; his mother, Dorothy; his sister, Sharlee; his grandmother and grandfather, Dorothy and Bill Connors; and his wife Hannah. As for his two young daughters, Bella and Story, Jeter said he “looks forward to being there to support whatever dreams they have.” Also among the well-wishers was Jeter’s close friend, NBA Hall of Famer and basketball legend Michael Jordan.

Jeter was the last of the quartet of inductees to speak. He was greeted by the chants he heard so many times playing in the Bronx:

D–E–R–E–K J–E–T–E–R!

D–E–R–E–K J–E–T–E–R!

The new Hall of Famer said “it felt good” to hear the chant again.

“You forget how good it feels. It’s been a while. I think the last time I heard that many people chant it was at the ’96 World Championship team reunion (held in 2016 at Yankee Stadium),” he said.

The former Yankees captain said he never wanted to play any position other than shortstop, but there is a funny twist to the story.

“My dad coached me a couple of years in Little League,” he said. “He had me play second base and third base as well as shortstop. So probably the only time I didn’t play shortstop consistently was when I was playing for my dad.”

Always known for his fierce brand of play, Jeter said of his competitive spirit, “I think it’s innate. I think it’s something you always know you have. You talk about competition. Competition eliminates complacency, and you pay attention to your competition. I think at the same time, you are competing with yourself and never being satisfied.”

The great Yankees catcher Yogi Berra, who won 10 World Series rings as a player, would come to visit the team often at Yankee Stadium during Jeter’s career.

“He would always come over to my locker to remind me of how many World Series rings he had,” said Jeter, who won five World Series championships with the Yankees. “I used to joke with him and say, ‘Well, you know, it’s a little bit harder now because there are more rounds in the playoffs,’ and he just went right to the World Series. His response was, ‘You can come over to my house and count the rings any time you want.’

“So I always felt I was chasing something. That’s the only way you are going to improve. You always have to try to get better and, to me, getting better meant winning more.”

Jeter is now CEO and part-owner of the Miami Marlins. He said he always gets a chuckle when young players today come up to him and say, “You were my favorite player when I was a kid.” That gives him pause to think about his legacy.

“The most important thing to me during my playing career was to be remembered as a Yankee. That was it,” he said. “That was the only team I ever wanted to play for, since as far back as I can remember. So that’s what I wanted my legacy to be.

“As you start your career, you begin to realize that your legacy is so much more than what you do on the field. It’s about what you do off the field as well. Whether it’s the work done through my foundation in New York, Michigan and Florida, or what I’m doing down in Miami, baseball has been a big part of my life and will continue to be. So, I think when you talk about legacy, post–playing career, I’m still working on it. But during my playing career, I wanted my legacy just to be a Yankee.”

A RARE CANADIAN BASEBALL STAR

Larry Walker’s storied career is unusual because he didn’t play baseball in high school. His high school didn’t even have a baseball team. Walker hails from Maple Ridge, British Columbia, where, he said, “every kid dreams of being a hockey player. Baseball was just something you did in the summer while you waited for hockey season to start.”

Walker played baseball in the Maple Ridge youth leagues. He didn’t even realize he was being scouted by any major league teams.

“I think Toronto was interested and maybe the Cubs. But there was minimal talk about it, so I can’t say if it was real talk or not,” he said.

But the Montreal Expos were excited about signing the Canadian native. He caught the eye of both Jim Fanning and Bob Rogers, both seasoned baseball pros with the Expos, and was signed to a contract in 1984.

“I came into baseball a little raw and a little behind everyone else. So they gave me the opportunity to learn the game,” the seven-time Gold Glove winner said.

Walker, 54, is only the second Canadian-born player and the first position player from Canada to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. His fellow countryman, Ferguson Jenkins, a standout pitcher from 1965-83, was the first Canadian player to be honored with a plaque in Cooperstown.

“Obviously, it’s a big thrill to be able to join Fergie and be one of two who have made it from north of the border,” he said. “It’s beyond a big thrill to have the maple leaf tattooed on my arm and to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame.”

In his induction speech, Walker recalled how much he loved hockey as a youngster and wanted to play in the National Hockey League. He had played organized hockey since he was 7 years old. But he didn’t get the breaks when it came to making it in Junior Hockey, a critical step en route to the NHL. Meanwhile, Walker continued to play baseball as a teenager and softball as well. The Montreal Expos took note of his power at the plate and his natural swing.

“To my adopted home, the United States, I thank you for allowing this Canadian kid to come into your country to live and play your great pastime,” Walker said.

He added that he hoped his induction would inspire other Canadian youngsters who dream of playing in the major leagues to work hard and follow their dream.

“I share this honor with every Canadian,” Walker said.

He thanked all three teams he played for but was especially grateful to the Expos for signing him and giving him a chance to break into the major leagues.

Walker sports a Colorado Rockies cap on his Hall of Fame plaque, however. He had some of his best years with the Rockies, batting .334 in 10 seasons in Colorado and winning the National League Most Valuable Player award in 1997.

Even now, after he has had a long time for the idea of being inducted into Cooperstown to sink in, Walker still said he doesn’t consider himself a Hall of Famer.

“I take everything in my life as just an average guy,” he said. “I don’t put myself on a pedestal and never have in anything. And I don’t recall any time in my career where I actually looked at myself in the mirror or sat there thinking I was a Hall of Famer. I just played the game to win.”

Walker had 2,160 hits and 383 home runs to go along with his lifetime .313 batting average. He also won three National League batting titles (1998, 1999, 2001) and the National League Most Valuable Player award in 1997.

A LONG ROAD

For Ted Simmons and Marvin Miller, the announcement of their selection to the 2020 Hall of Fame class came on December 8, 2019 at Major League Baseball’s annual Winter Meetings. That’s when the Hall’s Modern Baseball Era Committee selected the two worthy candidates.

Simmons, a switch-hitting catcher, played for the St. Louis Cardinals (1968–1980), the Milwaukee Brewers (1981–1985) and the Atlanta Braves (1986–1988). The hard-nosed backstop batted over .300 seven times. He had a lifetime average of .285 with 2,472 hits and 1,389 runs batted in. Simmons is wearing a St. Louis cap on his Hall of Fame plaque.

Simmons grew his hair long during the 1970s as a member of the Cardinals. Those flowing locks gave him the look of a lion and, combined with his ferocious play, earned him the nickname “Simba.” His hair still flows, but it’s a bit grayer now.

Simmons has been retired for 33 years. At 72, the eight-time All-Star remarked that it took him a while to get a plaque in the Hall of Fame. He told the crowd that there are many roads to Cooperstown.

“For those like myself, the path is long. And even though my path fell on the longer side, I wouldn’t change a thing,” he said.

A Detroit native, Simmons reminisced about growing up in the Motor City and idolizing Detroit Tigers greats like Al Kaline, Norm Cash, Rocky Colavito, Frank Lary and Bill Freehan.

“In my youth, Kaline was my hero,” he said. “As I stand before you as a man, he remains my hero today.”

Kaline passed away in April 2020 and was one of 10 Hall of Famers who died since the last induction ceremony in 2019. All were given a special tribute as part of the ceremony.

Simmons talked about his post-playing days, when he had various front-office jobs in baseball, including as a farm-system director, general manager and major league scout.

“My role on the administrative side of baseball has been just as important to me as my active playing career,” he noted.

He spoke lovingly about the game during his induction speech.

“Baseball is about all the names and faces that remain firmly planted in one’s memory,” he said. “My major league experience as a player was long (21 years), and the rosters of those teams listed many great players. They also listed countless others, not nearly as recognizable, but their faces remained with me just as indelibly.”

Simmons was traded by the Cardinals to the Milwaukee Brewers in 1981. The Brewers made it to the World Series in 1982, where, ironically, they lost the Fall Classic to the Cardinals in seven games.

Simmons said that when he woke up on the morning of his Cooperstown induction, it felt like the seventh game of the 1982 World Series.

“It was that kind of anxiety — that kind of anticipation. And when I felt it, I recognized this feeling as happening only one other time in my entire professional life, and that was the seventh game in 1982,” he said.

A TRAILBLAZER

To many, Marvin Miller is considered one of the most important figures in baseball over the past half-century or so. He was the first executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, better known as the “players’ union.”

Miller served from 1966-1982, turning the MLBPA into one of the strongest unions in the country. By challenging the baseball establishment, Miller changed the financial landscape not only for baseball but for the entire business of sports. He was called both a sports union pioneer and a trailblazer.

Miller passed away in 2012 at the age of 95. His Hall of Fame plaque was accepted by Donald Fehr, who served as the union’s general counsel under Miller. Fehr then became the union’s executive director after Miller retired in 1982.

Miller was born in 1917 and grew up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn as a Dodgers fan. Fehr told the crowd that Miller graduated from New York University with an economics degree. “He was not a lawyer, as many thought,” his successor noted.

Miller negotiated the players’ union’s first collective bargaining agreement in 1968. In addition, he won salary arbitration as part of the players’ collective bargaining agreement in 1970; fought and eradicated Major League Baseball’s reserve clause; led the players through three strikes (1972, 1980, 1981); and ushered in free agency.

Under Miller’s leadership, the average salary for a major league player rose from $19,000 to $241,000 a season. Fehr said Miller convinced the players that “playing Major League Baseball is a job. It’s not a game —something that children do.”

He described Miller as “quiet and soft-spoken.”

“He was polite, thoughtful, deliberate, fiercely, incredibly intelligent, extraordinarily and meticulously well-prepared, incisive and decisive, and always very patient,” he said.

Establishing the players’ pension fund was something very close to Miller’s heart and a key issue for him, Fehr recalled.

He said Miller was a great teacher.

“How did he do that? He would assemble the facts and analyze the issues,” Fehr said. Miller would then turn that information over to the players and let them discuss the issues openly, the former counsel to the MLBPA said.

“Most important, Miller trusted the players. He said any number of times, ‘Give the players the facts and they will make the right decisions,’” Fehr said.

Before Miller was elected by the Modern Baseball Era Committee, he was passed over seven times for induction.

“On behalf of all the players I represented,” Fehr said, “I want to thank Marvin Miller, because the game was not the same after his tenure as it was before. It was and is much better for everyone. You brought out the best in us and you did us proud.”