News

Butch Jacobs Shares Details Behind Topps Basketball Cards

By George Vrechek

In previous articles, SCD talked to retired Topps Director of Photography Butch Jacobs about the process of selecting photos for baseball (Aug. 7 issue) and football cards (Sept. 18 issue) during his tenure with Topps from 1973-2007. We continue that thread by looking at Topps basketball card photos with input from Jacobs and others.

It was great for collectors that Topps got back into the basketball card market in 1969. The 1969 issue contained primarily rookie cards in that no national card issue had been on the market since the 1961 Fleer set. Topps came out in a big way with big cards of the tall boy format in both 1969 and 1970. There were no action photos and no team logos shown, but at least it was a start.

We learned in interviewing former Topps Director of Photography Butch Jacobs that Topps didn’t always obtain licenses from both the leagues and the players associations. Football and basketball cards were not as financially important at the time as baseball cards, or probably even the non-sports cards, and it made sense to Topps to limit their costs. Football cards in the 1970s were just licensed with the players’ association and not the NFL. Consequently, if photos contained a player wearing a logo that was considered trademark property, the Topps artists would airbrush out the offending features. For portraits, Topps would avoid showing helmet logos.

Since basketball players didn’t wear helmets, and initially Topps didn’t use action photos, you would think that the portrait photos would look pretty normal. They didn’t. You would also think that since photographers could get very close to the action on the court that the in-action photos would be easy. They weren’t.

Earliest cards

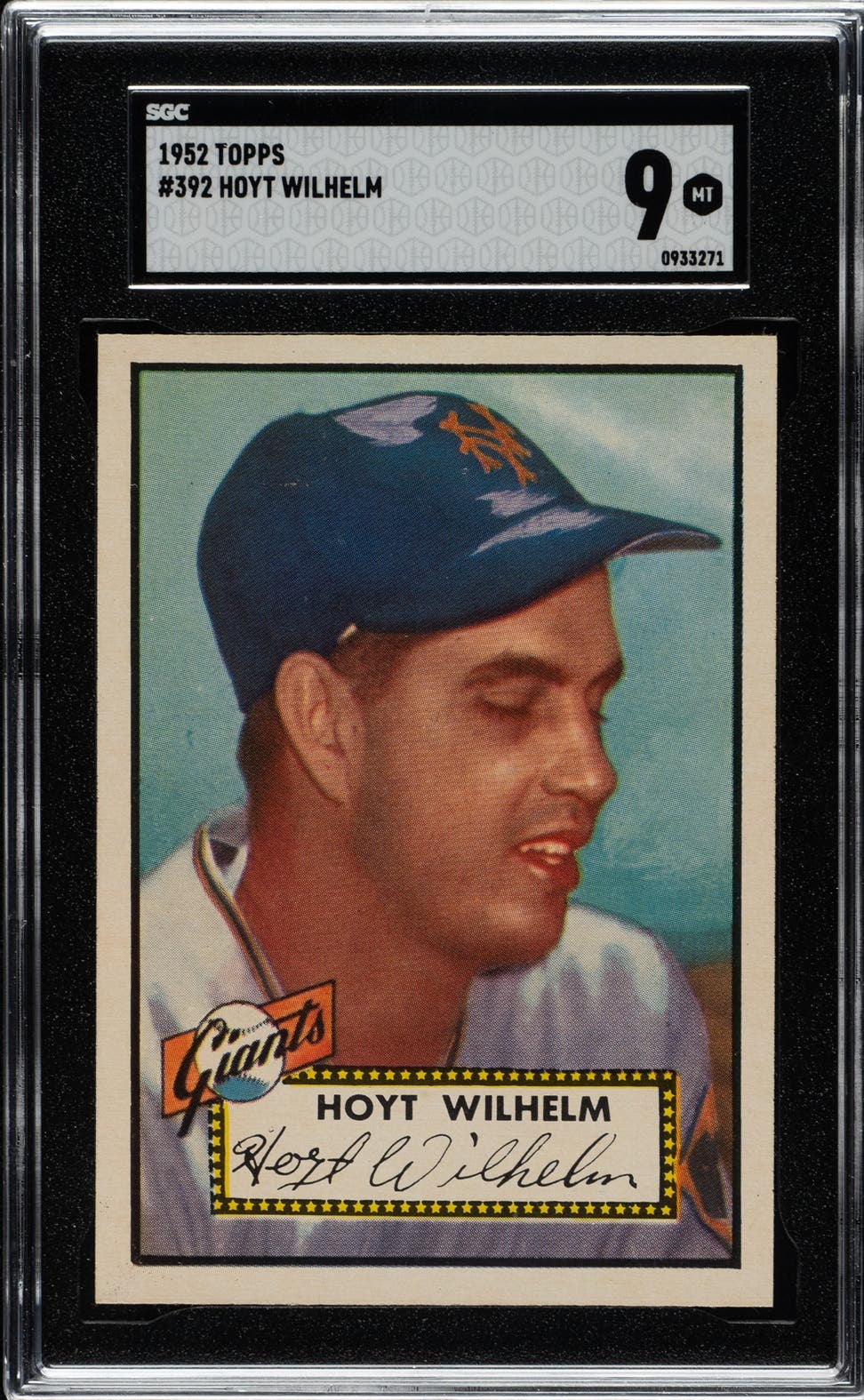

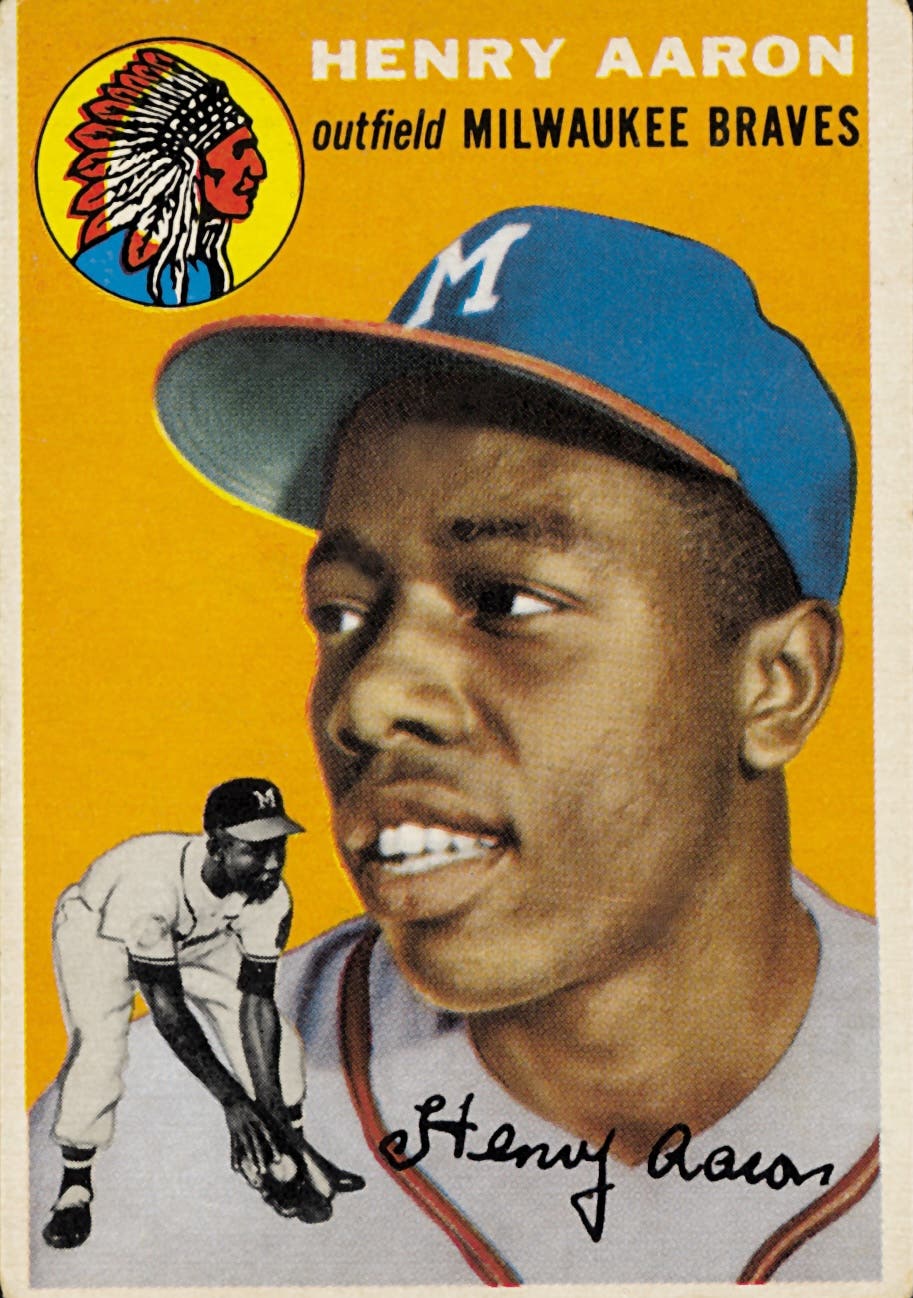

A look at the nationally distributed basketball sets before 1969 doesn’t take too long. Bowman’s one and only set from 1948 showed the Basketball Association of America players primarily in posed portraits wearing their jerseys displaying either the team nickname or the city. The 1957 Topps cards had many in-action photos of NBA players like Schayes, Cousey and Russell, which looked good, although not quite as good as the 1957 Topps baseball cards.

Collector and writer Jim McConnell remembers talking to the late Bill Haber of Topps about the 1957 set. Haber preceded Jacobs in selecting photos for card sets and called the 1957 basketball set a huge flop. The black-and-white 1961 Fleer set had action photos and even included team logos.

From a licensing standpoint, you would have to assume that Bowman, Topps and Fleer had agreements that allowed them to show players and team uniforms. The NBA Players Association started in 1954, although they didn’t get active in negotiating collective bargaining agreements with the league until the late 1960s. In 1967, the NBA created an entity to handle team licensing called NBA Properties.

Topps is back in 1969 with a funny look

Topps reappearance in the basketball card market in 1969 comes with a realization that something is going on as to license agreements. Some players are wearing their jerseys normally. Others have on warm-up jackets. Many players have their jerseys on backward, displaying a noticeably higher neckline as well as their name and number but no team name. They look like they got dressed in the dark, and their wives didn’t straighten them out before they went out the door.

Card collectors are interested in whatever juicy details can be uncovered regarding old cardboard. I talked to former Topps employees Jacobs and Len Brown, as well as Ira Friedman, the current vice president of licensing at Topps. Arthur Shorin was the CEO of Topps for many years and started working with Topps in 1958. I contacted him to see what he knew about what was going on with the jerseys. His response was, “Beats me.”

1969 Jersey-wearing mysteries

Jacobs, though, remembered not being able to show team nicknames, although city names were apparently fair game. This hint explained most of what puzzled me about the 1969, 1970 and 1971 Topps basketball cards. All three sets included players with their jerseys on frontward or backward, as well as players wearing warm-up jackets or plain T-shirts. Today, with some exceptions, NBA home teams wear light jerseys and usually have the team nickname on the front. Road jerseys are dark and may have the city name instead of the nickname on the front. Team names are legally considered “distinctive” and can be trademarked, whereas city names are “generic” and can’t be trademarked as the property of a team. Topps had an agreement with the players’ association in 1969, but not the league, which allowed them to show players and team uniforms to the extent the uniforms didn’t show any trademarked property.

In general, if a player had a jersey handy for the 1969 photos with a “generic” city name, they wore it facing forward showing the name. It looks like Milwaukee, San Diego, Detroit and Philadelphia had such jerseys available. If the photos were taken and the players only had “distinctive” team nicknames on the front of their jerseys, then the photographer had a few options. In some cases they had the player hold a ball in front of them to cover the majority of the team name, they had the player turn sideways so that you couldn’t see the front of their jersey or they would have the player put on his jersey backward so that you saw the player’s number and name as well as a very high-necked jersey. The silly-looking backward jersey would seem like a last resort, but perhaps it was safer and less confusing to have the photographer instruct everyone to just put their jerseys on backward. Consequently, there are many players in these three sets wearing their jerseys backward.

The Knicks had “New York” on the front of both their home and road jerseys, but wore them backward anyway. Traded players, relocated or new franchises and airbrushing jobs added to the jersey confusion. The NBA had their famous “dribbler” (Jerry West) logo back in 1969 but it didn’t make it onto team uniforms until about 1981 and wasn’t an issue, which the airbrushing artists and photographers must have appreciated.

Poses in 1970 and 1971

The 1969 set had only 99 cards, while there were 168 players in the league. The 1970 set had 175 cards with several special cards. There were many “common” players who appeared in one set or the other but not both. Based on the poses, jerseys and haircuts of some of the players appearing in both sets, Topps probably took photos of all players on all teams in 1969 and used some of those photos for the 1969 set and others for the 1970 set.

The 1971 set of 233 cards showed a noticeable change. The first two-thirds of the set consisted of NBA players covering up or reversing jerseys with team names. The last third of the set featured rival ABA players with no qualms about which way their jerseys faced, an indication that Topps made a deal with the ABA that allowed them to show both players and logos. The ABA started in 1967, but did not merge its four remaining teams with the NBA until 1976.

The 1971 cards included team nicknames in the boilerplate on the front of the cards. The Topps copy editor must have decided that the proper way to punctuate a team nickname was to add a possessive apostrophe after plurals ending in “s.” Hence the names used are Bulls’, Knicks’, Pistons’, etc. To me, it begs the grammatical question: The Bulls’ what? Perhaps the punctuation was intended to avoid a question regarding use of a trademarked team name? Future sets deleted any more business with apostrophes, which made me feel much better.

License expands to NBA Properties in 1972

It was likely that Topps had a three-year license agreement with the National Basketball Players Association to produce cards for 1969, 1970 and 1971. In 1972, the Shorins and Sy Berger must have determined that it was cost-effective to pay for a league agreement and be able to show logos. Topps must have had such an agreement with the ABA for the 1971 and subsequent sets. Topps apparently obtained licenses from the NBA to be able to show team names and logos in the 1972 and subsequent sets.

At some point, perhaps as early as 1972, the mechanics of the dual licensing was simplified into Topps dealing with just the league. The league would have an agreement with the players. Currently, NBA Properties (an affiliate of the league) handles trading card licensing through a group license with the players’ association which is confirmed in their collecting bargaining agreement. (They do not, however, return any phone calls on the subject.) There are still players in the 1972 set with backward jerseys; however, a few NBA and most ABA players are pictured with team nicknames prominently displayed on the fronts of their jerseys.

My guess concerning the 1972 set is that while it was possible that some photographers got the word about NBA team names and logos in time to photograph them normally and others didn’t, it is more likely that logo-obscured photos were used from the prior years. Topps photographer Doug McWilliams identified photos used by Topps in the 1973 set as having been taken by him at the same time as the photos used for the 1972 set, and it is likely the same approach was used in the prior years.

By 1973 the floodgates opened and jerseys and logos were all over the cards. With the licensing restriction out of the way, it was much easier to use action photos of players, which finally started appearing in the 1972 set and increased considerably each year thereafter, creating a new set of challenges. Apparently, the economics for using NFL logos on football cards differed since Topps didn’t enter into a license to use NFL logos until 1982.

1973 Bathroom photos

The 1973 set included more action photos, and Topps ditched the colored background approach used for portraits in the three prior sets. However, for the many posed portrait shots showing players dribbling or holding a ball, the photos look like they were taken in locker rooms, hallways or practice areas. In many cases the players stood in front of a cinder block wall on tile floors with vinyl molding. Jacobs remembered these early 1970s photos and called them “the bathroom photos.”

Selecting players and rookies

With only 12 players on a team, Jacobs said the photo shoots were more manageable, with fewer photos and less travel involved than for baseball and football. He felt, “The stars seemed to stick around longer and make a bigger impression.”

Rookies usually didn’t get onto cards until their second year in the league. Jacobs recalled that rookies weren’t a “lock” to make the team, and that there were many draft rounds of players who were never seen again. As with the football cards, Topps put together sets at about the same time the NBA draft was held. They didn’t necessarily have photos they could use for the rookies. However, Jabbar, Maravich, Murphy and Walton were on rookie cards their first year in the league. Calvin Murphy is in a Niagara University uniform, which has been partially airbrushed. Pete Maravich is clutching a ball which covers his LSU jersey. Bird, Erving, Magic, Hayes, Cowens, Gervin, Lanier and other big-name rookies waited a year for a card. Jacobs said he worried about getting a current card of Bill Walton each year with his latest haircut and beard because, “You didn’t know if he was going to be injured or not when you got around to doing photos.” Walton’s injury problems turned into a lawsuit against the Trail Blazers and their doctors.

Photography challenges

The 1974 set continued the evolution showing jerseys and action. Portraits were superimposed over a monochromatic action background. Jerseys and backgrounds were looking better; however, action photos were not always easy. Jacobs discussed problems with camera angles and indoor lighting.

While photographers were almost on the court, they were shooting very tall players from a very low angle. When players took jump shots or went for rebounds, the angles got even worse. You might wind up with a very good view of a player’s armpit but not his face. Dark hairdos would also look funny from a low angle with a dark ceiling background.

Jacobs remembered, “Topps artist Norm Saunders would be muttering to himself because they would have to wind up repainting or outlining a player’s hair so that it wouldn’t disappear into the background.” They would “feather in the changes right on the transparencies” according to Jacobs.

Lighting

The lighting in arenas varied considerably. Some of the tungsten lighting used in older arenas would produce a yellow or orange tint to the photos. Topps wanted their photos to be consistent and the color differences could be noticeable. Photoshop software wasn’t available until 1990. The only recourse Topps had was to throw out yellow-tinted photos. Jacobs remembered not being able to use photos taken at some arenas at all. The photography from older, dark arenas wasn’t helped by the inexpensive cardboard used to print the cards. Jacobs jokingly called it the “gray shoebox stock.”

Improvements

Gradually photographic techniques, cameras, lenses and arena lighting improved. The newer arenas had much better lighting and might include special flash lighting for photography. Action photos or candid portraits with logos became the norm before Topps took an untimely 10-year break from issuing basketball cards after 1982.

Photographers earned their money by coming away with usable images given the challenges of licensing, courtside angles and the variety of lighting. Butch Jacobs poured through thousands of images to come up with what would work for the Topps cards. We appreciate being able to hear how it happened.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to SCD and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.