News

Hobby Royalty Remembering Rocky Colavito

It was one of the most shocking trades in the long history of the game, a dastardly deed so foul and lamentable that the man who engineered it was burned in effigy. With one stroke of the pen, Cleveland Indians General Manager Frank “Trader” Lane sent one of the most-beloved players in the history of the franchise off to arch rival Detroit.

Rocky Colavito, slugger supreme in the Midwest in the late 1950s and early 1960s, was one of the great stars of the American League in a period that also included names like Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris and Al Kaline. But it was Colavito, the reigning American League home run champion in 1959 with the matinee-idol good looks and a rocket for a throwing arm, who commanded a following unmatched in the blue-collar outpost of Cleveland.

Arguably one of the greatest players of his era, he performed deeds that thrilled a generation of American League fans, including a game where he hit four home runs that cemented his reputation as one of the game’s top sluggers.

He ended up a with a sterling 374 career home runs and 1,159 runs batted in, but the numbers hardly tell the story of the Bronx native who grew up 20 blocks from Yankee Stadium, and rooted for the Yankees and their Hall of Fame center fielder, Joe DiMaggio.

But the Yankees wouldn’t match the contract offer the Indians came up with, and he signed with the organization at age 17, just as his idol, DiMaggio, was stepping away from the game.

As a young player who didn’t get a good solid look at the major league level until he was nearly 23, Colavito was occasionally accused of spending too much time and effort emulating the Yankee Clipper rather than developing his own style. Ironically, although he had turned down a chance to sign with the Yankees when he was a youngster, he would end his career as a Bronx Bomber in 1968, essentially dividing his final major-league campaign between stints with the Dodgers and the Yankees.

That one fateful trade a half-century ago in April 1960 ended up seeming to define what was nearly a Hall of Fame career. Despite his status as one of the pre-eminent sluggers in the league, Rocky would spend only four years in the Motor City before being unceremoniously dispatched – in order – to Kansas City (1964), back to Cleveland the next year, to the White Sox in 1967 and then to the Dodgers and finally the Yankees the next year. That seemed like no way to treat a six-time All-Star and one-time home run champion, and no way for such a remarkable career to end.

Conspiracy theorists have long pointed to that confounding trade, even to the point of noted sportswriter Terry Pluto penning The Curse of Rocky Colavito: A Loving Look at a 33-Year Slump, in 1994. The book placed much of the blame for nearly three dozen seasons of Cleveland woe right at the feet of Frank Lane.

Pluto’s timing turned out to be much better than Lane’s: the next year the Indians won their first pennant in 41 years, but the nimble scribe found ways to follow up his popular tome with sequels Burying the Curse (1997) and Our Tribe two years after that.

For fans too young to remember that darkest of days on April 17, 1960, when Rocky was swapped even-up for 1959 American League Batting Champion Harvey Kuenn, all of the anguish probably seems overblown. Not so.

“It was a shock. You know, everybody worried about how it affected me, yet hardly anyone talks about how it affected Harvey,” Colavito said in a 1990 interview in SCD.

“I always felt bad about that. I got most of the publicity. It was a little different in Cleveland with all the fanfare, but the fans loved Harvey in Detroit. I know it fouled him up. I often think about it. His first wife had a real problem dealing with it ... She was gorgeous and had been Miss Wisconsin. She was a beautiful person. She had a mental disorder after that, and I often think to myself that the trade had a lot to do with it ... She later died.”

That’s the sad part of the famous trade that’s not as widely known: the upheaval in Cleveland was the biggest part of the story at the time. According to Colavito, it more or less came out of the blue as the 1960 season unfolded, with neither player getting in so much as a single at-bat for their respective soon-to-be-former clubs. The 154-game schedule at the time allowed the regular season to begin at a more civilized (read: warm) point on the calendar, rather than the April Fool’s mischief that reigns today.

“The only thing that might have taken away 100 percent shock was that it was mentioned one time over the winter of 1959-60,” Colavito continued. “Lane blamed me that we didn’t win the pennant in 1959 (the Go-Go White Sox edged the second-place Indians by five games), even though I hit 42 home runs. That’s the kind of person he was. Lane could never keep a secret; there was just that one rumor that there was going to be a trade of Kuenn for Colavito, but that was it. Never heard it again.”

That is until it was a done deal, and one that set in motion more than three decades of mind-numbing mediocrity for generations of Cleveland fans who arguably had penance enough to face just for attending games on the chilly banks of Lake Erie. I guess I should add the caveat “if you believe in Pluto’s underlying premise.”

For many, many fans, the ensuing days in mid-April 1960 involved vows that they would never return to the park. “The attendance went way down,” Rocky recalled.

The man who would stand in the on-deck circle and do stretching exercises with his Louisville Slugger that would leave the ladies swooning, probably never topped the above comment in the realm of major-league understatement.

After an 89-65 campaign and a pennant near-miss in 1959, the 1960 club would skid to below the .500 mark, ending up in fourth place at 76-78, with three different managers having had a crack at reversing the debacle.

And a total of 950,000, just about 550,000 fewer fans than had been on hand to watch Rocky sock 42 homers the year before. That’s a drop of 37 percent in a single season, a staggering drop-off in 1950 dollars or even the inflated ones of 50 years later.

Such carnage should have resulted in the megalomanic Lane (he had once tried to trade Stan Musial) being run out of town on a rail, but the end was less flashy than that. In January 1961, he left Cleveland to take an executive position with the Kansas City Athletics.

Rocky should have gotten the last laugh, but if he did it wasn’t immediately forthcoming. Arriving in Detroit dazed and bewildered that April 50 years ago, he struggled mightily in his first appearance.

“You talk about shock,” Colavito recalled in that 1990 SCD interview. “I had the worst day, pressure wise, in my entire career my first day with Detroit. We played the Indians, and I was 0-for-6. I struck out four times and hit into a double play. I had never struck out four times in a game in my entire life.”

The next day he snapped out of it with a home run off Cleveland ace Jim Perry, and ultimately turned in a solid if less-than-spectacular inaugural season with the Tigers. The real fun would start in 1961.

By that time, Kuenn was already gone from Cleveland, shipped off to San Francisco. Rocky helped propel the Tigers to their best season in 15 years, socking a career-high 45 homers and knocking in 140 runs. It was only because of the peculiarities of coincidence that neither figure led the league: with Mantle and Maris setting the baseball world on its collective ear, 45 home runs got you fifth-place ranking in the league for round trippers; his RBI total left him in third place.

“That was a wonderful season,” Colavito related in a later SCD interview in 1998. “I’ll tell you how it could have been better: we could have won. I wanted that so bad. I wanted to be on a championship team in the big leagues so bad. We won 101 games and should have won the American League title. I bet 99-out-of-100 years we would have won the league with 101 wins, but that year it didn’t happen.”

And despite having such an incredible season – and 1962 was no slouch, either – the honeymoon with the fans that had been the order of the day in Cleveland never really got off the ground in Detroit.

At one point he charged into the stands to challenge a drunken fan who had been insulting his wife and his father; he would also have an initial clash with famed Detroit sportswriter Joe Falls when Falls – acting as the official scorer – charged Colavito with an error that the outfielder felt was undeserved.

As the year went on, and indeed throughout Colavito’s stay with Detroit, Falls would track a kind of snarky, informal statistic he had dubbed RNBI, for Run Not Batted In.

Not surprisingly, Rocky didn’t care much for this statistical anomaly, and the chilly relationship would prevail for his stay with the Tigers, though they did reconcile a bit in later years, which Falls noted in his own biography, Joe Falls: 50 Years of Sportswriting (and I Still Can’t Tell the Difference Between a Slider and a Curve).

Colavito would return to Cleveland with a sense of vindication and a bit of a flourish for two productive campaigns in 1965-66, but even that was not without controversy. Some sportswriters contended that the club gave up too much to engineer the return of the by-then 32-year-old slugger in one of those three-team blockbuster trades that were more common (read: feasible) in the giddy pre-free agency days of the 1960s.

The Indians ended up sending a young Tommy John off to the White Sox, along with another promising talent, Tommie Agee, both of whom had their best years ahead of them. Colavito was far from finished, making his final two All-Star appearances and clubbing 26 and then 30 home runs, but now the end was near.

Playing with four different teams in his final two seasons, he managed to tack on a mere 16 more home runs to a total that looked like it had Cooperstown potential in the innocent days of that gauzy era when the pitchers dominated for their final period of the millennium.

A Hall of Fame near-miss

In the years since the baseball card hobby exploded on the national scene, the uber-popular Colavito is frequently mentioned when talks of immortality flares up, and his unique stature among collectors does nothing to diminish that view.

Colavito’s 1957 Topps rookie card is a monster in its highest grades, and an expensive card for a guy without a plaque in Central New York. His stature was such in 1960 that the Hartland Plastics Co. in Hartland, Wis., included Rocky on its ground-breaking roster of 18 lifelike statues that sold for a couple of bucks at the time in department stores and at the local five and dime.

While the likes of Babe Ruth, Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Ernie Banks, Rocky found himself in good company indeed for that historic offering that would ultimately become a highly coveted collectible.

While some of the statues like local favorites Warren Spahn and Eddie Mathews are thought to have had castings as high as 100,000 to 150,000 pieces, the Colavito statue (and the even rarer Dick Groat) were likely limited to between 5,000 and 10,000.

That can make high-grade examples of Rocky’s Hartland pretty expensive, and even more when the original box and the quirky little red tag are also included.

As an aside, I no doubt passed by lots of Hartland statues as a kid, opting instead to spend my limited funds on the Topps cards that seemed elusive enough in my meager tax bracket. So when a later resurrection of the Hartland franchise returned to the hobby in the 1980s, I made sure to pick up as many of the “Anniversary” statues as I could afford.

Included in that group was an unpainted Colavito that I requested, and promptly turned around and painted him in an Indians uniform, ie., the way that God intended for Rocky Colavito to be portrayed, be it in plastic, bronze or just about any metal or man-made synthetic material you can imagine.

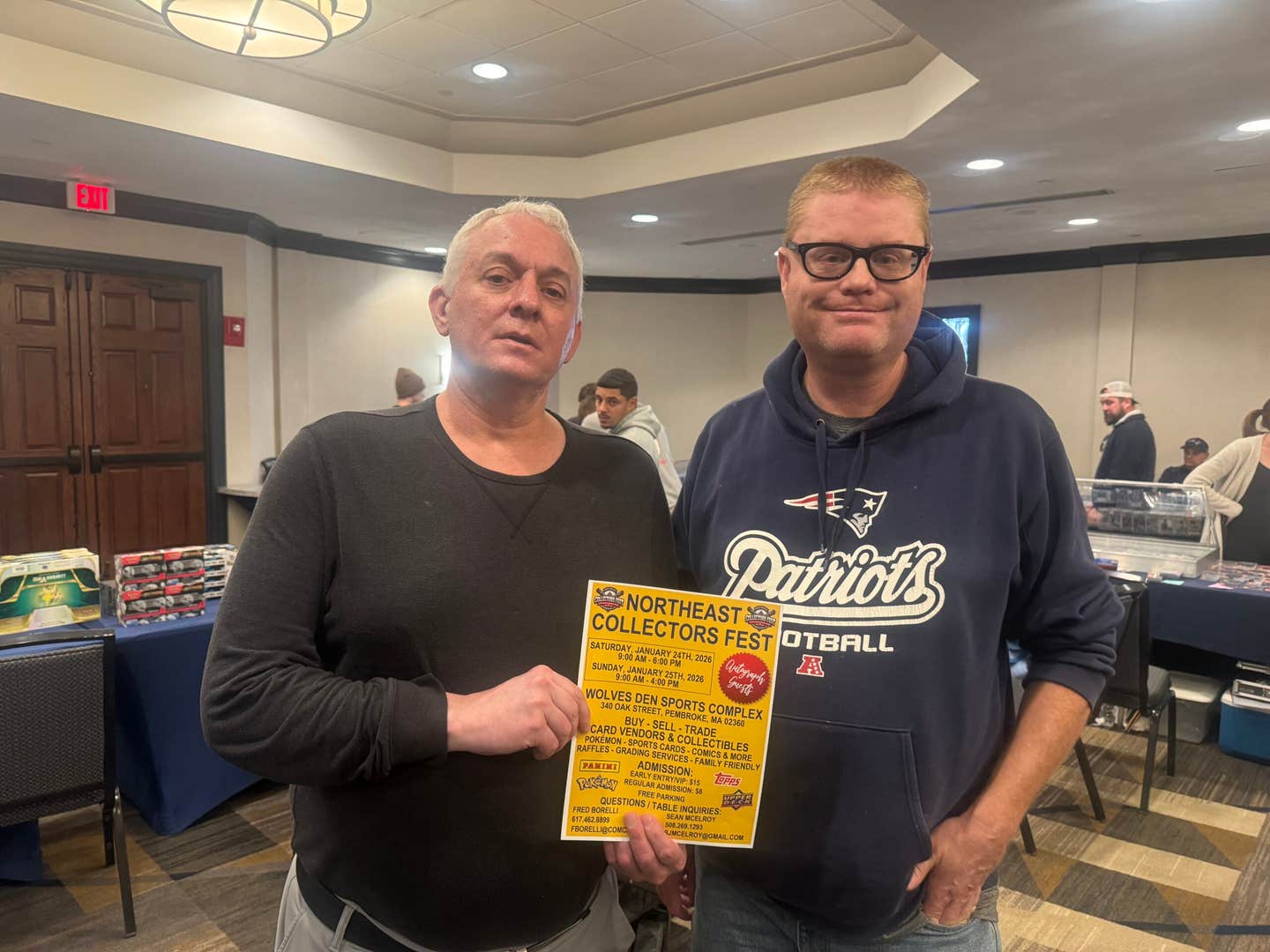

And then I turned around and sold it to a guy in Louisiana named Harvey Weber. He bills himself, quite fairly as I understand it, as “Rocky’s Biggest Fan,” and as the picture on the pages suggest, his allegiance to the Cleveland legend knows no bounds. I still regret selling that statue to this day; at the risk of sounding immodest, I did a good job of painting the Indian logo on the sleeve, to say nothing of the lettering on the shirt. But I digress.

As the adjacent chart showing the prices of some of his cards and memorabilia illustrates, Rocky Colavito can command big prices for those items in top condition, even without the exaggerated rarity that accompanies something like the Hartland statue. What would it be if he were a Hall of Famer to boot?

Like one of his famous contemporaries from that era, Roger Maris, Colavito is certainly a long shot candidate to ever see a plaque bearing his likeness, and it’s no secret he’s none too pleased with that situation.

“That’s kind of a sore spot with me,” he said in a 2007 interview with the Boston Globe. “I see some players with lesser credentials, and that bothers me some. I told my wife and my son, ‘If I die and they want to put me in, tell them to stick it, ’cause it ain’t gonna do me any good when I’m dead.’

“There were better players than me – they could run more – but I held my own. I was the RBI king one year (1965). I thought I contributed to my team, I never dogged any ball. I went something like 232 games without an error. But it’s a popularity contest.”

There’s more than a little irony there, because in his prime, there was nobody more popular than The Rock. You just had to be in the right neighborhood.