News

Rush Limbaugh not alone in wanting to protect our borders …

Actually, I tend to get Lou Dobbs and Rush Limbaugh mixed up, but I am pretty sure that either or both of them pretty consistently opine about the need to protect our borders, and on that question I can certainly agree.

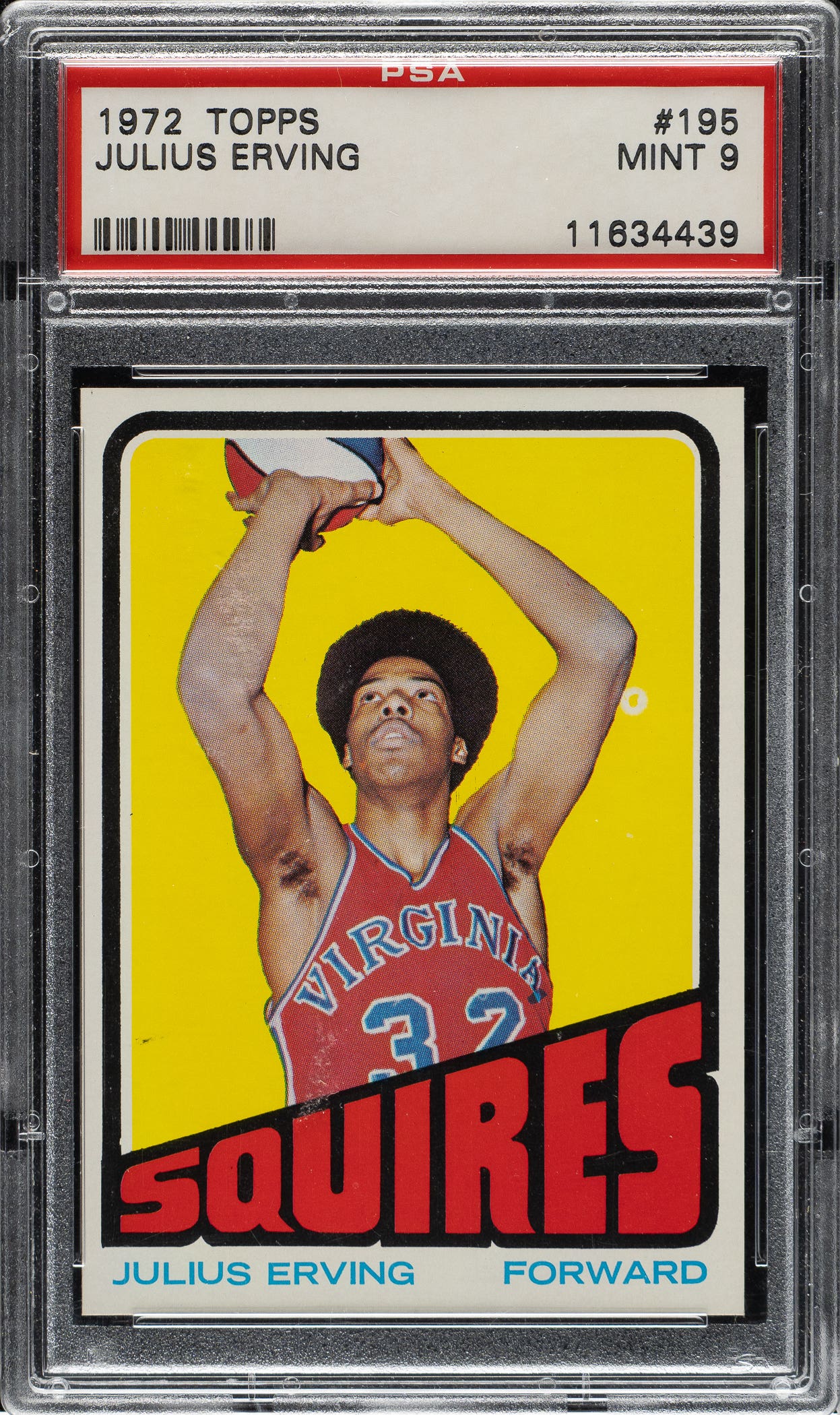

Of course, the borders I am talking about are cardboard, rather than the more consequential ones that they are referring to. No matter: In the arcane world of sports cards, the border can be pretty important stuff.

What got me thinking in this odd fashion was a story told by veteran vintage-card deal Bill Nathanson of The Polo Grounds, a first-rate purveyor of high-grade cards from the 1950s and 1960s.

Nathanson recounts a rare moment when he had to return a customer’s money after selling him three or four 1954 Topps Baseball cards. The man insisted that the cards were off-center top to bottom, maybe even miscut, since there was no top white border at all.

Nathanson patiently tried to explain to the man that the iconic 1954 issue doesn’t have a top border but instead has the white border only on three sides. The man would have none of it, and ultimately the good-natured Nathanson returned the cards under the heading of: “The customer is always right, even when he’s wrong.”

The longtime dealer theorized that the man might have first been acquainted with the wonderful 1954 Topps Baseball issue through the reprints that were produced in 1994, and those have the white border all the way around.

So borders can be important, even more today than they probably were 20 years ago, since as hobbies mature there tends to be a greater emphasis placed on condition. That very same significance also leaves those white – or even worse, condition-sensitive color – borders susceptible to a lot of mischief. If you don’t believe me, get a hold of some of the vintage Topps treasures where the white borders have been bleached and you’ll see what I mean.

But for the graphic designers, what seems like a very pedestrian element can be pretty dramatically off-kilter when a problem develops. Fleer, which didn’t have a great deal of baseball card experience when it produced its Baseball Greats issue in 1960, found this out the hard way.

At this juncture, the card company stumbled with arguably the most important card in the set: No. 72 of Ted Williams, the only “modern” player included in a set populated by Hall of Famers and mostly long-retired stars. It was the only card of Williams produced that year, which was his last. Seems he would be the victim of odd cropping like this to the end of his days and even beyond.