News

A look back at the Negro Leagues on 100th anniversary

On May 2, 1920, the inaugural season of the Negro National League commenced in Indianapolis. It was the first of several professional baseball leagues known as the Negro Leagues. Tom Edwards takes a look back at the Negro Leagues, celebrating their 100th anniversary.

I saw my first Major League Baseball game in 1954 when my father took me to see our hometown Brooklyn Dodgers play the Milwaukee Braves at Ebbets Field. As long-time fans know, both teams had great players. For me, there was one player in particular that stood out: Jackie Robinson. I was 5 years old at the time and told my father that was the player I was going to follow. My father had followed baseball since he was a kid and was very knowledgeable about its history. He told me that at one point in his career, Jackie had been a member of the Kansas City Monarchs, a Negro Leagues team, and he was the player that, seven years before I saw him, broke the color barrier. That conversation began an interest in the Negro Leagues that has continued for 66 years.

Prior to Jackie’s history-making first game at Ebbets Field, as was the case with most of the film footage shot before 1947, baseball was being played in black and white. Along with Jackie—to this day the most electrifying professional athlete I have ever seen—Hall of Fame players that were in the Negro Leagues before signing with major league clubs include Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin and Roy Campanella. Among Hall of Famers that spent all or a majority of their careers in The Other Major League are Buck Leonard, James “Cool Papa” Bell, William Julius “Judy” Johnson, Ray Dandridge, Negro Leagues founder Rube Foster, Josh Gibson, John Henry Lloyd, Oscar Charleston, Martin Dihigo and the one and only Leroy “Satchel” Paige. During his Hall of Fame induction speech in the picturesque village of Cooperstown, N.Y., Ted Williams said, “I hope that someday Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall as symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given a chance.” As history has shown, Ted’s hope became a reality five years after his induction when Satchel was inducted with Josh to follow.

Andrew “Rube” Foster, whose Hall of Fame induction was in 1981, was the Founding Father of Negro Leagues baseball and the driving force behind the first successful league for black players. He began his career in 1897 as an 18-year-old pitcher with the Austin Reds. At the turn of the century, he signed a contract to join the Chicago American Giants for $40 a month. It was as a member of that team that he mastered a great screwball. In an exhibition game against the Philadelphia Athletics, Foster earned a victory over eventual Hall of Famer Rube Waddell and acquired a new nickname. At about that time, he assisted New York Giants manager John McGraw with some pitching tips for McGraw’s star pitcher, Christy Mathewson. Prior to Foster’s help, Mathewson had a career record of 33-37. Subsequent to Foster’s tutoring, Mathewson’s win totals for the next three seasons were 30, 33 and 31.

Having been interested in the facet of baseball history that is the Negro Leagues, my wife Cathy and I had the pleasure of establishing a friendship with 1938 Negro Leagues batting champion Lou Dials of the Chicago American Giants. After a memorabilia show where I had the pleasure of giving him some help, Lou reached under the table and gave me a replica of the Louisville Slugger bat he used during his career. I had played baseball in Little League, in high school and a little in the military, and Lou’s bat was, shall we say, well above my pay grade. It was both longer and heavier than what I used. I took a few swings, sort of, and gave up. I still remember a short exchange we had. I asked him “Lou, how did you swing this?” Without hesitation he replied, “Very well.” No doubt. The bat is engraved “1938 Negro League Batting Champion .382 Avg.” With a lifetime batting average over .300, I asked what he thought he would hit if he were playing today. He thought about it and I was surprised when he said, “Probably about .280.” Understandably I said, “Really. Do you think the pitching is that much better?” He said, “No, I’m 87 years old!”

Lou lived in L.A. and Cathy and I, at the time, lived in San Diego and we always made it a point to get together. Lou was as charming as he was pleasant and informative. I told Lou I had a number of Negro Leagues books and asked him about Cool Papa Bell. Lou told Cathy and me about a game they had played in and a play he remembered. He said Cool hit a shot that went right through the pitcher’s legs and was headed for center field. I asked Lou how it turned out. He said, “Well, it probably would have been a double, but as he was sliding into second base, the ball hit him, so he was out.” Satchel Paige said Cool could flip a light switch and be in bed before the light went out, so Lou’s story confirmed how fast Cool was. James Bell received one of the best nicknames in the history of sports when he rounded first base during a really hot afternoon game and, between innings, the first base coach said James “created a cool breeze” when he ran past him. His 24-year career began in 1922 and ran until 1946. During that run, he was a member of the Kansas City Monarchs, the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords. While he was with Pittsburgh, Satchel Paige, Judy Johnson and Josh Gibson were teammates. They were managed by Hall of Famer Oscar Charleston and won the 1935 Negro League championship. Five Hall of Fame members on a team is impressive by any standard.

One of the other Negro League players I had the pleasure of spending time with was John “Buck” O’Neil of the Kansas City Monarchs. In 1962 he broke one of baseball’s last barriers when the Chicago Cubs hired him to coach third base; he became the first black coach in Major League Baseball. In 1960, he convinced the Cubs to sign a young man named Lou Brock. Trading him to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he had a Hall of Fame career, wasn’t Buck’s idea. He was a frequent All Star during his playing days. Into his 80s, Buck stayed active in the game as a scout for the Kansas City Royals. I have a number of books in my baseball library that cover Negro Leagues history and always found the title of his book, “I Was Right On Time” to be just right.

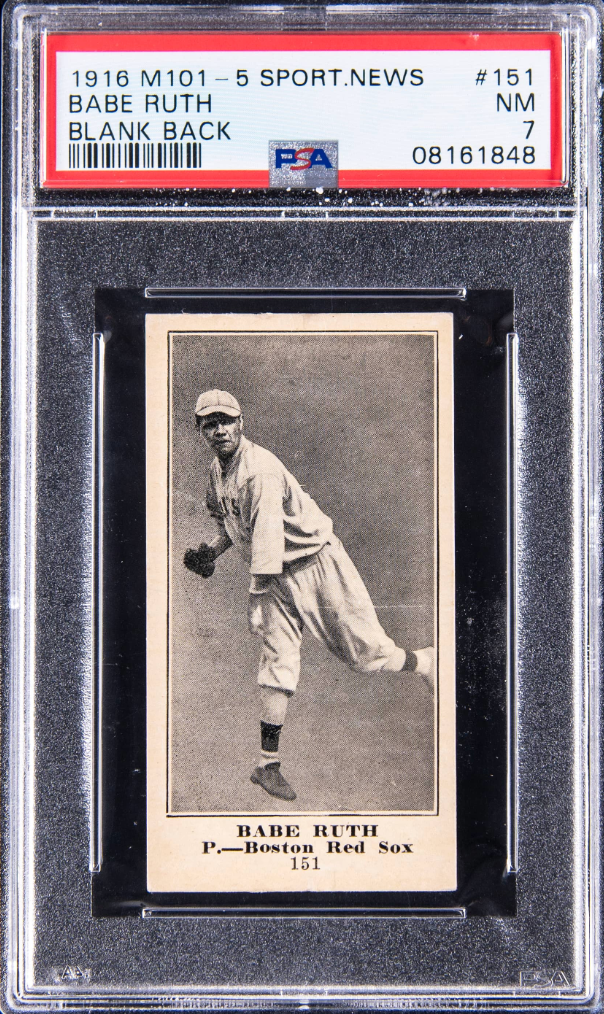

Many baseball fans will tell you catcher Josh Gibson is one of the greatest to play the game. His home run power is legendary. Having researched every possible source, historian John Coates has determined Josh hit 823 home runs from his rookie season in 1930 until a brain tumor ended his career in 1946. He died in January of the following year, three months before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. Checking out his 60 documented at-bats against major league pitching shows he could handle any team’s rotation. While facing Johnny Vander Meer, the only big leaguer to pitch back-to-back no-hitters, Dizzy Dean and his brother Paul, who lead the St. Louis Cardinals to the 1934 World Series title, Josh hit .426 with five home runs. One of my baseball cards from the 1960s was issued to commemorate Mickey Mantle’s 565-foot home run at Griffith Stadium in Washington. During the history of that ballpark only three home runs were hit to that section of the park. Josh hit the other two. He played most of his home games at Forbes Field where the center-field wall was 457 feet from home plate and Griffith Stadium with a shorter, but still challenging 421-foot distance. His overdue induction into the Hall of Fame was in 1972.

The most charismatic Negro Leagues player was Leroy “Satchel” Paige. Hall of Fame pitcher Dizzy Dean called Paige “The best pitcher I ever saw.” During an exhibition game against major leaguers, Paige recorded 21 strikeouts. After 22 years in the Negro Leagues, he was signed by the Cleveland Indians and was a 42-year-old (at least) rookie. He finished the season with a 6-1 record and helped Cleveland win the 1948 American League pennant. Always a big draw during his Negro Leagues career, the Indians drew 78,383 fans to see a night game when he made his debut coming out of the bullpen. For his first start, the attendance was 72,434. At 46 years young and pitching for the lowly St. Louis Browns, he won 12 games and became baseball’s oldest All Star. In Bruce Chadwick’s book “When the Game Was Black and White,” the What If section, using projections and research, lists what baseball records might have been without segregation. Paige leads in career wins with 602, single-season wins with 42, and single-season strikeouts with 402. When you look at his 42-year-old rookie season, those figures make sense.

Effa Manley established herself as a knowledge baseball executive with the 1935 Brooklyn Eagles and joined her husband as co-owner of the Newark Eagles the following season. The opening sentence on her Hall of Fame plaque states: “A trailblazing owner and tireless crusader in the civil rights movement who earned the respect of her players and fellow owners.” She was an innovative businesswoman. During World War II, she invited veterans to attend Newark Eagles games for free. Her teams didn’t lack for talent with Hall of Famers Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Larry Dolby, who went on to integrate the American League, Monte Irvin, Biz Mackey, Mule Suttles and Willie Wells on assorted rosters. In 1946 they defeated the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues World Series.

Jackie Robinson’s entry into the major leagues signaled the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues. Baseball’s segregation, which dated to a day far too many years ago, was finally over. During his Hall of Fame induction speech, A.B. “Happy” Chandler, the baseball commissioner when Jackie signed with Brooklyn, mentioned he was proud to have been in the office during that historic event. It came shortly after the end of World War II, and Chandler said if these men can be expected to risk their lives in service to this nation then surely, they deserve the opportunity to prove the game is, in fact, the national pastime.

2019 marked the 100anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s birth. Having seen him play, I believe for every major league player wearing his number 42 on Jackie Robinson Day (April 15) it is a great time to reflect on everything he accomplished on and off the field. It’s an impressive list.

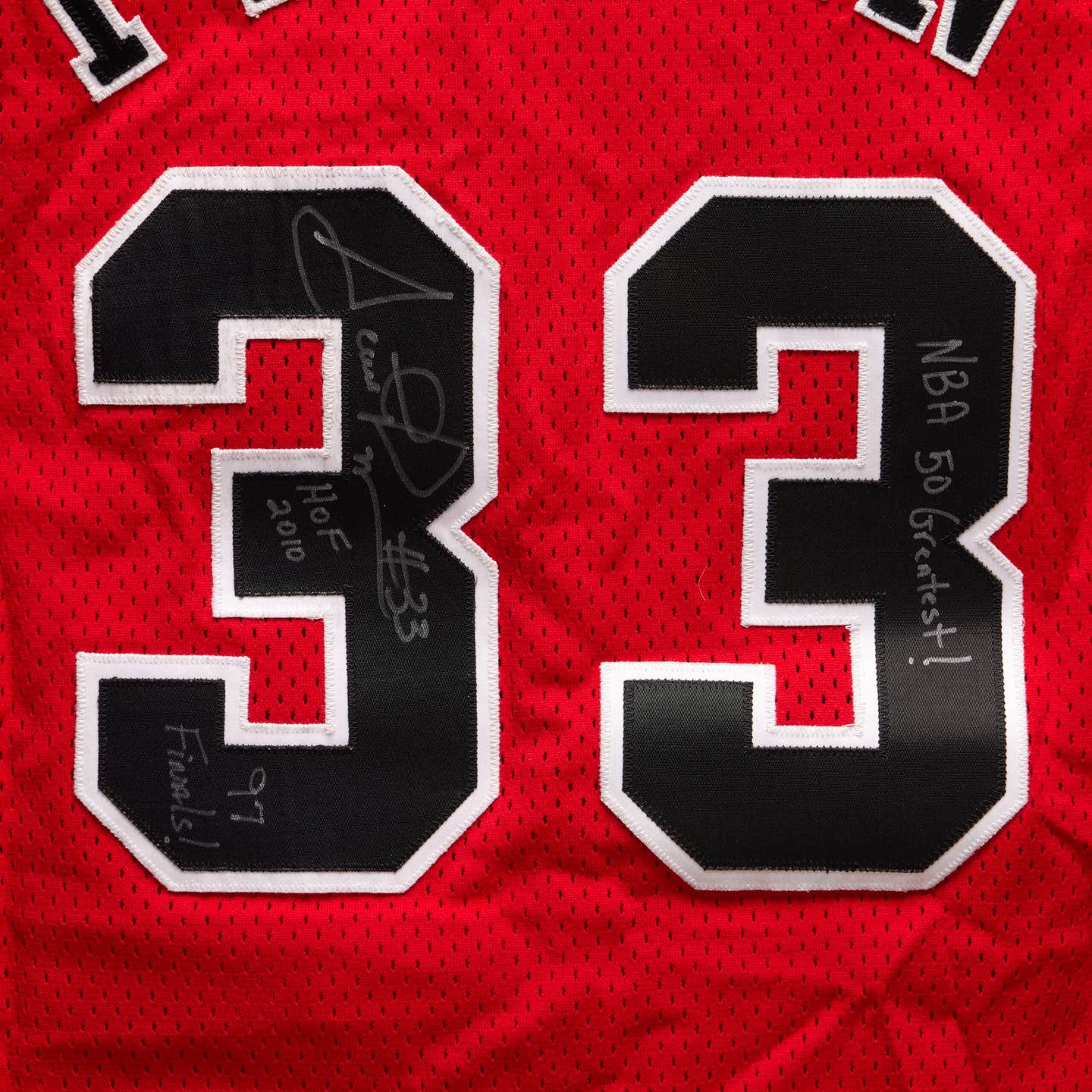

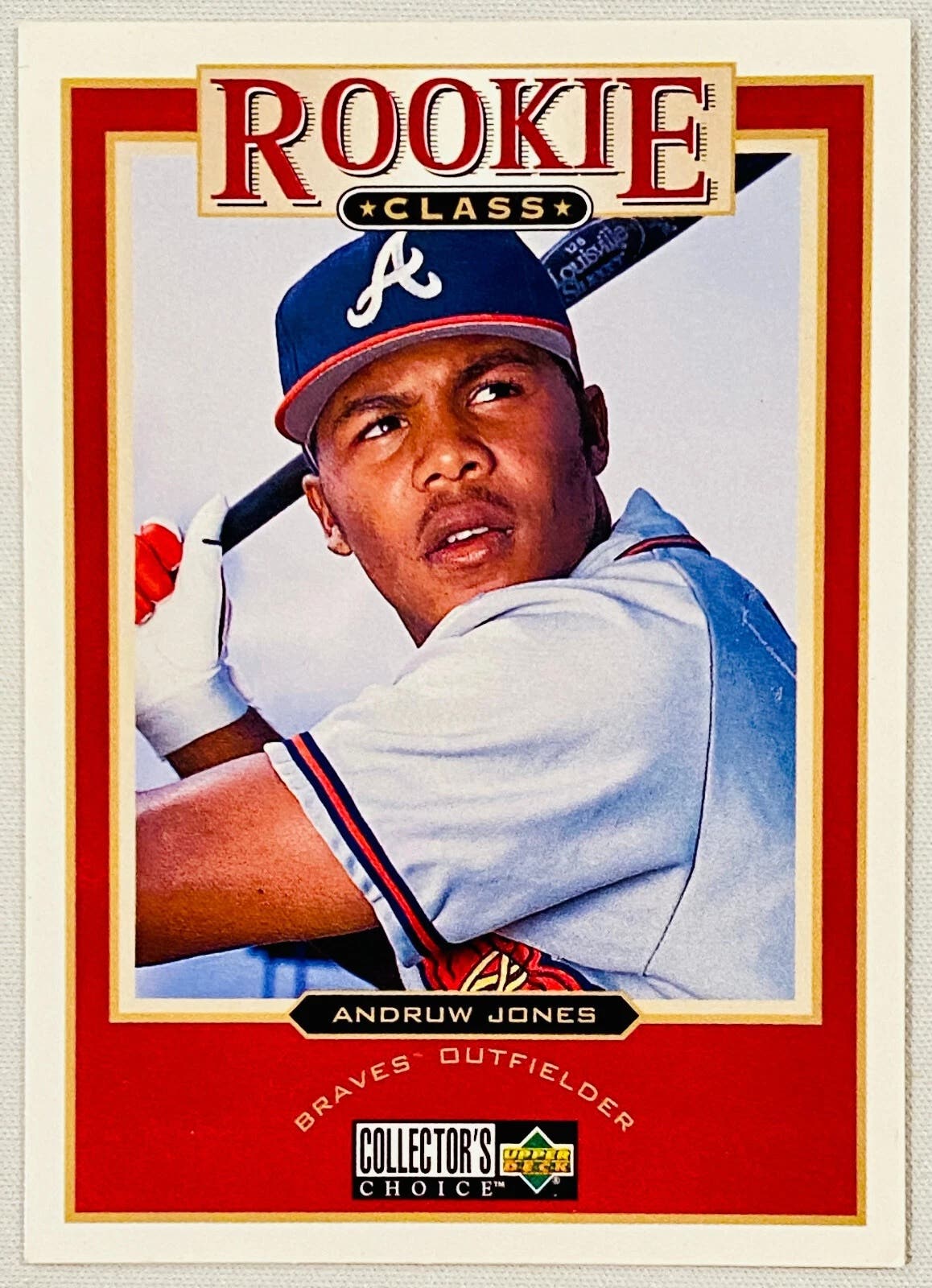

Fortunately for Jackie Robinson fans, as historic as his career was, a variety of memorabilia associated with it is not hard to find. 1997 was the 50th anniversary of Jackie’s first game with Brooklyn. Wheaties boxes featured three different photos for the three flavors available. One photo was used for all backs. Coca Cola had 50th anniversary Jackie-related product. The bottles and cardboard holder featured the 50anniversary logo. One of Jackie’s many great quotes, “A life is not important except for the impact it has on other lives” is on the front of the holder along with a photo of Jackie. Among the art associated with him, Perez-Steele postcards have been popular among collectors since their introduction. My Jackie postcard is next to the card of Negro Leagues Founder Rube Foster from that set.

As a fan of ballpark seats from Yankee Stadium (in 1923), the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field, it was fun to restore the Polo Grounds seats as they neared their 100birthday in 2011. After a fire on April 14, 1911, Giants owner John T. Brush had the ballpark rebuilt with steel and concrete. On June 28, 1911, the Polo Grounds was up and running. While researching a list of Polo Grounds and New York Giants-related books, I found one by Stew Thornley and enjoyed reading it. When my Polo Grounds seats restoration project was finished, I contacted Stew and asked if he would like to sit in seat No. 1 of my row of four and hold up a copy of his book. I told him about an article I wrote for SCD about the seat project. At that time, he told me he had another Polo Grounds book in mind and I replied that I would look forward to reading it. He thanked me, then asked if I would like to write a “couple of chapters.” That ultimately turned into three chapters. One of them is “Black Baseball at the Polo Grounds.” The book, “The Polo Grounds - Essays and Memories of New York City’s Historic Ballpark 1880-1963,” was edited by Stew Thornley, and it was fun to be given the opportunity to contribute.

One of the aspects I found interesting about the Polo Grounds was the Negro Leagues history that was made at the historic New York ballpark. The first game of the 1946 Negro Leagues World Series was played on Sept. 17, 1946. Representing the Negro American League was the Kansas City Monarchs. The Newark Eagles Negro National League champions were the opponent for the seven-game series. Unlike Major League Baseball World Series games, Negro Leagues World Series games were not always in a park of either team. In the seventh inning of the opening game, Satchel Paige hit. He singled and went on to score the winning run. For the Monarchs, a World Series appearance was a fairly common event. That wasn’t the case as often for the Eagles. However, their owner Effa Manley and manager Biz Mackey were part of the 2006 Cooperstown Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

In 1948, the New York Cubans became a New York Giants farm club. That being the case, when the Giants were on the road, the Cubans could schedule home games at the Polo Grounds. When the other two teams in town are the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers, the New York Giants found a way to fill seats at the Polo Grounds while on the road.When Jackie Robinson signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers and integrated Major League Baseball, the final days of Negro Leagues Baseball were not difficult to see. The list of Hall of Fame players that played all or some of their baseball years in the Negro Leagues is impressive. Their impact on baseball history is significant.

Major League Baseball has reached the start of the 2020 season. The first game in the opening season of the eight-team Negro National League was on May 2, 1920. The Indianapolis ABC’s defeated the Chicago American Giants, 4-2, at Washington Park in Indianapolis. This year marks the 100anniversary of the start of a fascinating chapter of baseball history.

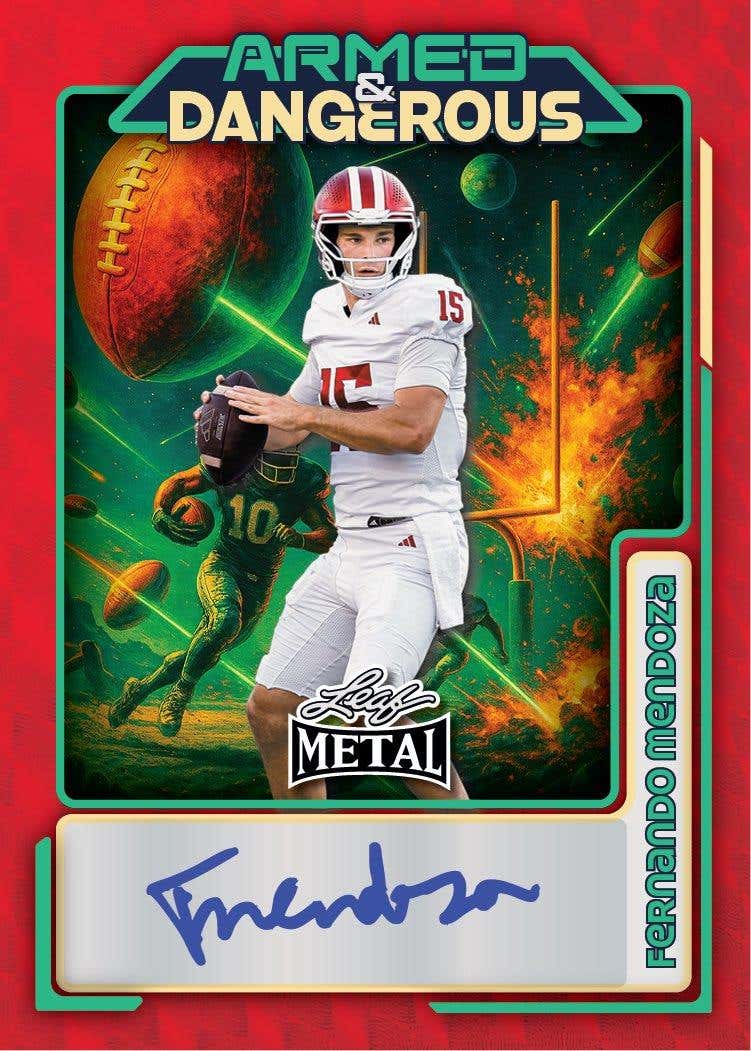

Photos of memorabilia from Tom Edwards and his collection.