Vintage Card Sets

Little-known 1895 Mayo tobacco cards another ‘Monster’ set from 1890s, early 1900s

Soon after entering the hobby, every beginning sports collector learns of “The Monster,” the set of 524 tobacco cards known as T206 that was issued between 1909-1911.

As the novice collector becomes more knowledgeable of earlier cards, his research will inevitably lead him to an even more “monstrous” issue from two decades earlier. This, of course, is the Old Judge cards of 1886-1890. The Old Judge set is known to contain thousands of cards (no one is sure exactly how many) of hundreds of players from dozens of leagues, major and minor. But all are readily identifiable by the manufacturer, “Goodwin & Co. New York,” usually at the card's bottom. Most of them are also labeled “Old Judge Cigarettes” or “Old Judge Cigarette Factory” somewhere on the card, although some of them instead advertise “Gypsy Queen Cigarettes.”

However, in neither case did any single tobacco manufacturer enjoy a monopoly. The T206 set was issued and distributed in packages of no less than 16 different brands. Further, other distinct sets were available at the same time from other makers, including Ramly, Obak, Turkey Red and Mecca. Likewise, in the last years of the 1880s, cards could be found with tobacco products other than Old Judge and Gypsy Queen, like Allen & Ginter, Kimball and Hess.

So a collector in the 1886-1890 or 1909-1911 time frame had more product that he could possibly find or afford.

What was the sports card market like in the two decades between those “Golden Ages?” The obvious answer is “pretty dismal.” The reason is equally obvious. In early 1890, Goodwin combined with four other giant tobacco firms to form the American Tobacco Company, or ATC. Smaller companies either sold out to ATC, went out of business, or continued to produce their cigarettes, cigars and chewing tobacco for a small local market.

For all practical purposes, ATC was a national monopoly or “trust.” And with no serious competition anywhere in the country, members of ATC saw no reason to offer free premiums with their products, especially pictures of baseball players. It was certainly no coincidence that the second boom in tobacco cards began after a New York federal court in 1908 ordered the ATC monopoly broken up. The matter was resolved beyond all doubt when the United States Supreme Court concurred with the lower court in 1911 and ordered ATC to dissolve nationally.

There was, however, one small, unexpected and never explained exception to this near 20-year drought.

MAYO CARDS

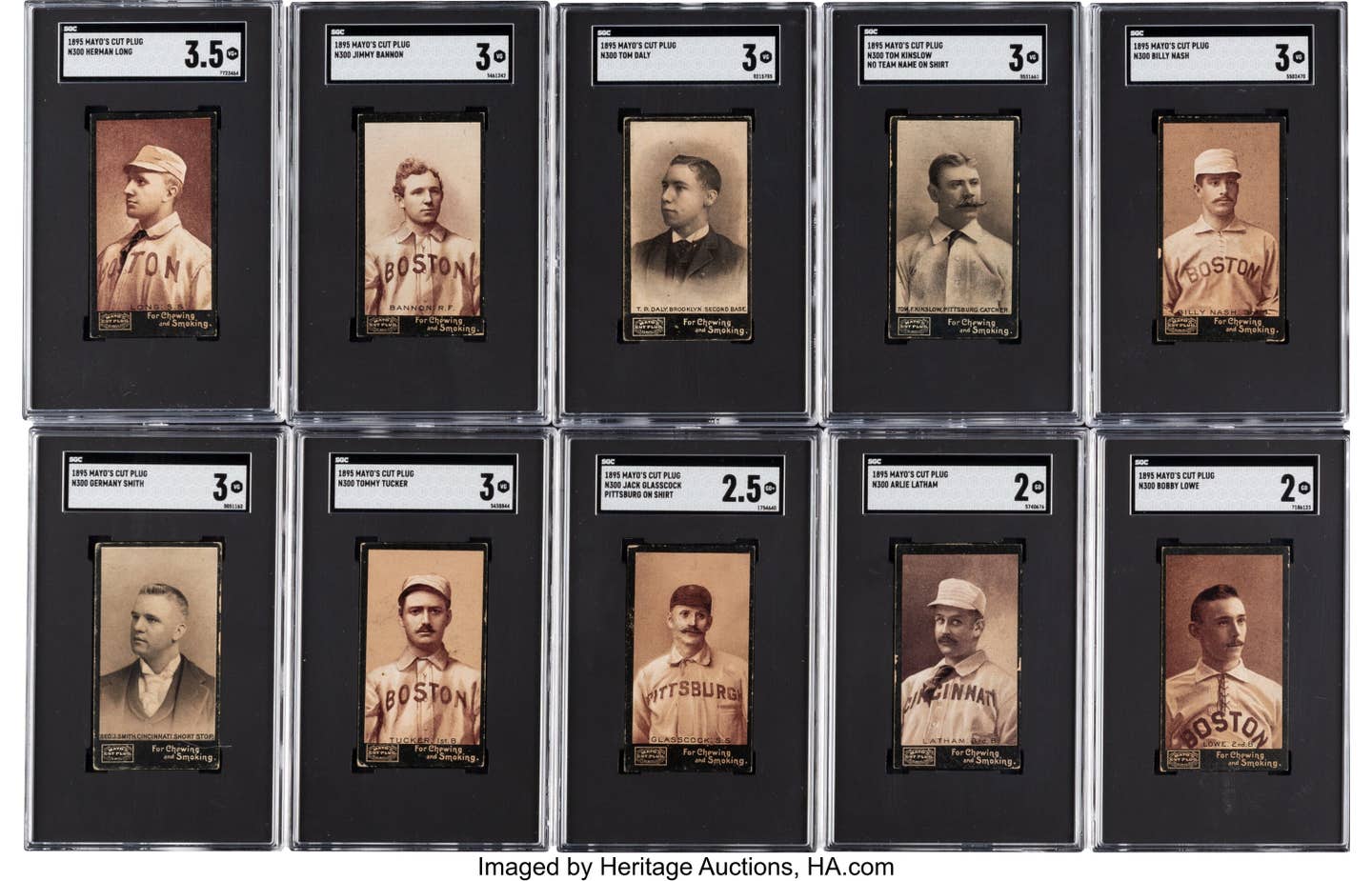

In 1895, the firm of P.H. Mayo & Brother of Richmond, Va., producer of Mayo's Cut Plug “chewing and smoking” tobacco, inserted one of 48 small cards in each tin or pouch of its product. The 1895 Mayos, catalogue designation N300, are of historical significance today as the only set issued in the decade of the 1890s and the most notable set issued between 1890 and 1909.

Unlike the earlier Old Judges and the later T206s, the cards are all close-up portraits, with no action poses, including several players shown in street clothes. The pictures are either sepia or black-and white shots, surrounded by a black border, and are surprisingly clear and attractive if one is willing to overlook the absence of color.

The cards are unnumbered and the only adornments on the card front are the Mayo's Cut Plug logo and the motto “For Chewing and Smoking” in the bottom border. Card backs are black and blank.

The cards, at 1 5/8-by-2 7/8 inches, are slightly larger than most early tobacco issues. The players are identified within the portrait in various ways. Cincinnati Red shortstop George “Germany” Smith is listed fully as “Geo. J. Smith, SS, Cinc.” Others have a first initial, such as “D. Foutz: 1st B,” while still others are merely a last name and position, such as “Ganzel: C.” or “Joyce: C.F.” This minimal identification creates the one unsolved mystery about the set.

There has always been speculation that the set was issued in late 1894, instead of—or in addition to—1895. This is because some players who switched teams in late 1894 or early 1895 are shown in the uniform of their earlier (1894) team. Hall of Fame catcher Buck Ewing is one. He can be found in the uniform of either the 1894 Cleveland Spiders (who released him in July of 1894) or the 1895 Cincinnati Reds (who signed him in December of 1894).

Similarly, “Pebbly Jack” Glasscock, sometimes called the best 19th Century shortstop, has two cards in the set, one with the Pirates (who released him in August 1894) and one with the Louisville Colonels (for whom he played only 18 games in early 1895). He is also one of the many players in the set with a great nickname, although the only one of these colorful nicknames to make it onto a Mayo's card was that of “Buck” Ewing.

However, it was impossible for the set to be issued exclusively in 1894, as some cards were undisputedly printed in 1895. One such definite 1895 issue is Pittsburgh Pirates backup catcher Tom Kinslow, who was not acquired by the Pirates from the Brooklyn Bridegrooms (later the Dodgers) until January of 1895. Like Ewing and Glasscock, Kinslow has a second card in the Mayo set. The cards have the same portrait with his magnificent mustache and the same caption—“Tom. F. Kinslow, Pittsburg, Catcher”—but one uniform shirt has no designation. In fact, the plain shirt version shows dark smudges, as if a team name has been erased by hand.

Further evidence of a 1895 issuance is found in the card of Washington Senators outfielder Charlie Abbey. It seems much more likely Mayo would issue a card of him in 1895 after his fine 1894 season, in which he played full time and hit .314 with 101 RBIs, than in 1894 following an 1893 season when he hit only .259 after a late season call-up.

So it seems more certain, but cannot be proved or disproved 125 years later, that 40 of the cards were initially printed and issued in early 1895. Further, the Mayo brothers in Richmond would have learned of a transaction, like Buck Ewing's signing with Cincinnati, only months after the fact. This explains the need for an eight-card update set in mid-1895 to account for seven player trades or retirements and a single error.

THE SET

So the 1895 Mayo Cut Plug set ultimately consisted of a total of 48 cards of 40 different players.

There was but one major league in 1895, the National League, then in its 20th year of operation. It consisted of 12 teams in one division. There were six teams on the Eastern seaboard, stretching from Boston to Washington, and six located in Pittsburgh and points west.

Despite finishing in the cellar in both 1894 and 1895, the Louisville Colonels are represented in the N300 set by two players in addition to 18-gamer Jack Glasscock. One is Hall of Famer “Big Dan” Brouthers, who can be found with a shirt reading either Louisville (his 1895 team) or Baltimore (his 1894 team). The third Louisville player is also among the eight variations. Second baseman Fred Pfeffer can be found either in uniform (as “Pfeffer, 2nd B, Louisville”) or in civilian clothes (as “Pfeffer, Retired”). Mayo undoubtedly assumed Pfeffer would retire after getting into only 11 games for the terrible Colonels in 1895, but “Fritz” Pfeffer did not retire after that season, going on to play two more years in New York and Chicago.

It may seem strange that a 35-96 team like Louisville in 1895 would be represented by three players among a total of 40. In reality, it was part of a very clever marketing strategy. Mayo made sure that all 12 NL teams were represented in its N300 set. An astonishing 10 members of the Boston Beaneaters (Braves) appear, from .440 hitter Hugh Duffy to 8-6 pitcher Tom Lovett. On the other hand, the Baltimore Orioles, despite having won the NL pennant in both 1894 and 1895, have only two players in the set, first baseman Brouthers and fellow Hall of Fame catcher Wilbert Robinson. Oriole outfielders (and future Hall of Famers) Joe Kelley and “Wee Willie” Keeler were both somehow omitted, despite hitting .393 and .371 respectively in 1894. In addition, the set contains but a single Cincinnati Red and St. Louis Brown (Cardinal).

That sole Browns player is the subject of the set's mystery.

There are no less than 12 Hall of Famers among the 40 players, some on more than one card. In addition to Brouthers, Ewing and Robinson, they are Cap Anson, Ed Delahanty, Hugh Duffy, Billy Hamilton, Tommy McCarthy, Kid Nichols, Amos Rusie, and John Montgomery Ward. “Monte” Ward, like Brouthers and Ewing, appears on two cards in the set, the latter in a business suit and labeled “Retired” after leaving the game with 164 pitching victories and over 2,000 hits.

Also See: Willie Mays' top baseball cards

The twelfth and final Hall of Famer is John Clarkson, who plays a central role in the set's mystery.

That mystery was created because Mayo's all-inclusive marketing plan required that they issue at least one card of the St. Louis Browns, which did not become the Cardinals until 1900 and were in 1895 only slightly better than the hapless Colonels. They did, however, have one future Hall of Famer on the roster in first baseman Roger Connor, who hit a fine .329 that season. But Mayo passed Connor over for a pitcher. That card's caption states only “Clarkson: P.” but the player's shirt reads unmistakably “St. Louis.” The Browns did have a pitching Clarkson on their 1895 roster. That was Arthur Hamilton “Dad” Clarkson, who finished the 1894 season with a 8-17 record and then started 1895 with an equally unimpressive 1-6 with St. Louis before the Browns traded him on June 8 of that year. But the face on the card is clearly not his.

John Gibson Clarkson, who was Dad's brother, pitched for four teams in his Hall of Fame career, amassing 328 victories over a mere 12 years. However, not one of these four teams was St. Louis. Further, he was not even active in 1895, having retired after an 8-10 season in 1894 spent entirely with Cleveland. Yet, the Mayo card labeled simply "Clarkson: P." is obviously John, not Dad. The two were not twins, much less identical, with John being five years older. Mayo, in fact, seems to have used the same picture of John that an artist used to create John's likeness on his 1887 Allen & Ginter “World's Champions” card. Yet the player's uniform is without doubt that of Dad's St. Louis team. The lettering is not crudely added by hand, but follows perfectly the shirt's folds and wrinkles.

Was “St. Louis” later somehow expertly printed onto a plain shirt? Alternatively, was John's head superimposed on the body of a St. Louis player? Were either of these things even possible with 1895 technology? Or was Mayo in Virginia able to simply obtain a pose of John in Cleveland in a uniform borrowed from Dad in St. Louis? Why did Mayo not just print a card of Roger Connor or another Brown? The answer has been lost for a century.

MAYO ERROR CARDS

Another of the Hall of Famers whose card was updated was Amos Rusie of the New York Giants. “The Hoosier Thunderbolt” led the NL in wins, strikeouts and ERA in 1894. He was so popular that fashionable Manhattan saloons named a cocktail after him. He was so popular that Lillian Russell, the era's most famous actress/singer/sex symbol, asked to meet him. He was so popular that, a generation before Abbott and Costello asked “Who's on First,” the comedy team of Weber and Fields featured in their vaudeville show a routine on his pitching feats.

Yet somehow Mayo misspelled his name as “Russie” in its initial run of N300s. The updated version contained his name spelled properly.

The set contains two other erroneous but never corrected names, those of Washington Senators pitcher Otis Stocksdale (misspelled Stockdale) and Philadelphia Phillies Hall of Fame outfielder “Big Ed” Delahanty (misspelled Delehanty).

The N300 set is popular today because of its historical importance and because Hall of Fame players are so heavily represented, with 12 of 40 players and 16 of 48 cards. In addition, three other players have received consideration for the Hall in the past and are still possibilities for induction. Besides Jack Glasscock, they are shortstop “Bad Bill” Dahlen and outfielder Jimmy “Pony” Ryan, both of the Chicago Colts (Cubs).

The set's popularity is reflected in the market. The set's cheapest cards, such as those of now-forgotten commons like Giants utility man “Yale” Murphy (a career .239 hitter) will cost the collector at least $100 even in poor condition. And the price curve for better condition cards and for Hall of Famers rises steeply upward into five figures.

OTHER MAYO SETS

Along with the N300 baseball set, Mayo released two other sets. One is the N302 set of 36 football players, all collegians from three Ivy League schools—Harvard, Yale and Princeton. They are the same size as the baseball players and, like the baseball set, unnumbered and black bordered portraits with blank backs. Players are identified only by last name and school, as “Acton, Harvard.” Again, some of them played in 1894 or earlier but at least one saw action only in 1895 so the set can be dated to the fall of 1895.

It is historically important as the only football set of the decade and the first ever exclusively football set. Thirty-four of the cards are of players whose names are unrecognizable today except to gridiron historians, although six of them are in the College Football Hall of Fame.

The N302 football set is harder to locate than the companion baseball set. For this reason the commons go for at least twice the price of a baseball common. However, none of them approach the astounding prices of the Hall of Famers in the N300 set, such as Cap Anson. And because the players are mostly unknown, even so-called “stars” like Langdon Lea and Arthur Wheeler will not cost much more than a common.

One Mayo football card is priced as a common but has an arguably prominent connection. The card of “Poe, Princeton” is that of Neilson Poe II. He is notable because his grandfather Neilson Sr. was the first cousin of author Edgar Allen Poe. The connection is interesting but adds little or nothing to the price of his card.

The set's final card is unique because the player is not named. For a century this card was listed in catalogues and price guides merely as “Anonymous.” It was not until the 21st Century that the player was identified as halfback John Dunlop of Harvard.

Because Mayo ceased printing this card when the error was spotted or for some other reason, few of these cards were issued. Less than 20 are known to exist today and it is arguably the most valuable football card in existence. It has been called “the Honus Wagner of football cards,” but this seems an exaggeration. While it is certainly scarcer than the Wagner T206, one brings only thousands, not millions, at auction.

The other companion set to the N300 Mayo baseball set is the set of 35 boxers issued at about the same time. The set, catalogue number N310, is usually dated to 1890 but this is an approximation made after the fact as some men in the set fought professionally as early as 1880 and others were active well into the 20th Century.

Its format is identical to that of the baseball and football sets except that the cards are printed on white, not black, cardboard and the first name of each boxer is given. Also, most of the pictures are posed action shots, not portraits, and every card can be found in two versions, with the boxer's name appearing either at the top or bottom of his picture. It is the least popular of the three Mayo sets, with commons going for less than half the price of a common N300 baseball player.

Similar to the football set, the names of most of the boxers mean little today. How many modern collectors even know that Charley Mitchell and George Dixon are in the International Boxing Hall of Fame? The set does have “stars” in “Gentleman Jim” Corbett and John L. Sullivan, whose card prices are comparable to those of the baseball stars.

An interesting third card pictures Joe Walcott. However, this is not the heavyweight champion of the 1940s and 1950s (real name Arnold Cream) who took his name from the earlier welterweight boxer of the N310 set and is called “Jersey Joe” Walcott to differentiate him from the original “Barbados Joe” Walcott.

Cards from all three Mayo's Cut Plug sets are available but expensive. Fortunately, all three sets can be found in reprinted but attractive form for a reasonable price, providing a realistic method for a modern collector to recapture three landmark sets of sports collectibles.

(A big shoutout to David Nemec for “The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball” and to SABR for “Nineteenth Century Stars,” both invaluable assets for researching baseball in the 1890s).