News

Interview With Former Kicker Don Cockroft

By John McMurray

Don Cockroft recalls how Sam Rutigliano, the coach of the Cleveland Browns, reacted after the team lost its first two games to start the 1980 season:

“We knew we had something good going in 1979,” said Cockroft, “and to start the 1980 season 0-2 was just so deflating. Coach Sam comes into the locker room, and said, ‘Look guys, can you live with a record of 14-2?’ and I think some of us were like ‘Sure, Sam.’ Then he got real serious and said, ‘Can you live with 14-2, ’cause we can do it.’ And after that, we lost only three games the rest of the season.”

The 1980 Browns team holds such an esteemed place in Cleveland lore for its spirited play and for its ability to win close games that Cockroft was inspired to write a book about the team’s season (The 1980 Kardiac Kids: Our Untold Stories). Cockroft interviewed every living 1980 Browns player and coach for the book, which took him more than four years to complete.

“I was talking with [former Browns wide receiver] Dave Logan, and he said to me ‘I think we caught magic in a bottle in 1980,’ ” Cockroft said. “None of us realized at the time what we were doing for the city of Cleveland. We didn’t realize it until 10,000 people showed up to meet us at the airport after we won in Houston earlier that day in Week 13 of the season. We had only won the ballgame, we hadn’t won the division title! When I talked to the players, one of their greatest memories was getting through that crowd at the airport.”

While Cockroft kicked for the Browns from 1968-80, he is often remembered for a kick he didn’t attempt: With the Browns losing 14-12 in a subzero home playoff game against the Oakland Raiders, the Browns elected to try to score a touchdown, resulting in an interception by Oakland’s Mike Davis, effectively ending Cleveland’s season.

“The whole book project really started when a woman asked me, ‘Why didn’t you get to attempt that kick against the Raiders?’ She pounded her fist on the table and said, ‘Why didn’t you kick? Why didn’t you kick?’ My response was: ‘Ma’am, you’re the 1-millionth person who’s asked me that question. I’m going to write a book about it.’

“Pretty much a day doesn’t go by when I’m not asked about not getting the chance to kick that field goal. When I moved back to Cleveland from Colorado 14 years ago, everywhere I went people talked about that team, almost as if they were family members. ‘Where’s Brian Sipe? Where’s Ozzie Newsome?’ they’d ask. It went on and on every day. That was the main reason I wanted to write that book. Everyone asked about that team, and the discussion always ended up with ‘Why didn’t you kick that field goal? Would you have made the kick?’

“Another reason why I wanted to write a book about that season was to explain the decision-making process. And then, when I began interviewing the players and got their stories, the project grew. I believe when you read the stories about the players in the book, about how they got to the NFL and the difficulties they faced, it’s a book about life more than it is a book about football.”

In spite of the windy and cold conditions in Cleveland, Cockroft does believe that he would have had the chance to kick the potential game-winning field goal in that playoff game if it had been fourth down.

“In that playoff game, we were certainly going to go out and kick the field goal had we not scored a touchdown by pass or by run,” Cockroft said. “Red Right 88 (the name of the play called which led to the intercepted pass) was on second down, and Coach Sam assures me even today that we would have kicked on fourth down.

“The big trivia question on the radio right at the time I retired was ‘How many kicks did Cockroft miss to win games?’ I went back and checked it. I was 17-for-17 with the game on the line during my career – most were field goals, but a few were extra points late in the game. I felt confident that I wouldn’t have been 17-for-18.

“Ozzie Newsome told me that the 1980 Cleveland team was the most unselfish team he’d ever been on,” continued Cockroft. “Guys truly didn’t care who it was who scored the touchdown. When you look at the first picture in the book, it’s of Henry Bradley. And very few people remember who he is, but he was the most inspirational member of the 1980 Cleveland Browns. His name was not recognized by most, but he gave 100 percent every time he stepped out onto the field. When we lost in Minnesota on the last play of the game, they had to kick the extra point. Guys were just standing out there because there was no time on the clock and the game was lost. And then Henry Bradley goes and blocks the extra point! You talk about an inspiration and a guy who gave his all. That’s what I want people to understand about this team.”

Cockroft, who ranks third in Cleveland Browns history in points scored, was the next-to-last kicker in the NFL (preceding only Mark Moseley) to use a straight-ahead kicking style. Cockroft does not believe that kickers will ever again employ the straight-on style.

“It will never happen,” said Cockroft. “That’s my prediction. A couple of reasons: Mainly, kicking straight-on is far more difficult. The primary reason for that is that when you kick straight-on, you’ve got to pull your foot up and you’ve got to lock your ankle straight. Moseley, literally, taped his ankle up. If you watch any old kickoffs of Moseley on tape, you can see he’s almost limping up to the football. He taped his right ankle from the lower part of his knee to his toes. He said he used three or four rolls of tape when they taped his ankles so he could have that ankle locked, or at least with less movement.

The easiest way to understand it is to hold your fist up with your fingers pointing toward you, and then to move your wrist. That’s what your ankle does. If your foot is turned ever so slightly, the ball’s going to go in that direction.

“I also punted for nine years while I was kicking, and I couldn’t tape my ankle, period, because I had to do just the opposite. So I had to point my toe down, and that made it especially difficult. After I quit punting, I did have them wrap my ankle, but not to the extent Mark Moseley did. So kicking soccer-style today is a major difference, and it is probably the biggest change in kicking.

“Conversely, the soccer-style kicker is almost punting the ball. The soccer-style kicker extends his foot downward, kicking the ball somewhere on the instep, and his foot is already locked by pushing it down rather than trying to pull it up. I would think that kicking soccer-style might actually be a little more difficult on the knee because in kicking straight-on, you’re using the quadriceps muscle for the power. Another reason you won’t see another straight-on kicker is that I don’t know that anyone is making square-toed kicking shoes anymore, like we used.”

Cockroft particularly admires the career of former Cleveland and current San Francisco 49ers kicker Phil Dawson.

“Phil Dawson is as good as anyone who has ever kicked in the NFL,” said Cockroft. “There is no one better – just check the record. There are a couple of guys who may have a higher percentage, and maybe they all fit into the same No. 1 category. But for Dawson to do what he did in the conditions in Cleveland, he’s the best, in my opinion.

“Things have definitely changed over the years when it comes to kicking. Now, you’ve got a center whose only job is to snap on field goals and punts. You don’t have someone who is just coming in and snapping the ball haphazardly anymore. You’ve got someone who will get the snap perfect 99 percent of the time. Now, the kicker probably never has to kick a lace.

“The conditions on the field itself have also changed for the better. Phil, as great as he was and as nasty as the winds are in Cleveland, he never had to kick in the mud. [Hall of Fame kicker Lou] Groza and I did. I remember [contemporary kickers] Jan Stenerud and Garo Yepremian saying almost identical things to me before games in Cleveland in late November, asking me, ‘Don, how do you kick in this place?’

“I also believe the ball has changed. My last year with the Browns, they said they actually put two bladders in it to help the moisture situation. The softer the ball is, the more it’s going to spring off your foot. I kicked the new ball, and I said, ‘This ball’s going five yards further than the other ball. I really believe the ball has changed; it’s softer today. When Dawson pushed on that ball, it really caved in. The old ball that we had, the one inflated with 13 pounds of pressure, you could have stood on that ball, and it wouldn’t have indented as much as the new one did when Dawson just pushed on it! I can’t see how kickers today could be that much stronger than we were. I really can’t. I’d like someone to prove me wrong.”

Cockroft fondly recalls Cleveland’s Hall of Fame kicker Lou Groza, who coached Cockroft for the first two years of Cockroft’s career with the Browns.

“I was picked to play in the college All-Star game, which used to be against the world champs, and then it was the Green Bay Packers,” said Cockroft. “It was played in Chicago. So, as a rookie, I was there during the first part of training camp and had never suited up with my new teammates, the Cleveland Browns. I was a third-round draft choice. So we played Green Bay, and the following day, then I joined the Browns just prior to participating in the Hall of Fame Game in Canton, Ohio.

“At that point, I had never met any of the Cleveland players. So I went up to Lou in the locker room, shook his hand and introduced myself. We were out kicking extra points to begin our warm-ups in the pre-game. Back then, the goalposts were only 10 yards from where you kicked the ball because they were on the goal line, and it was hard to miss an extra point.

“I knew Lou had kicked more than 100 consecutive extra points without a miss at one point in his career. So I’m trying to make conversation with him, and I said, ‘Lou, it’s hard to miss from here. It’s only 10 yards.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but you can miss.’

“So I went out to kick my first extra point as an aspiring Cleveland Brown, and it wound up being a perfect onside kick. I wasn’t even close. And I blame it on the grass. I couldn’t even see the ball (laughs). I kicked it so badly, I said ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’ When I go over to the sidelines, there to meet me was Lou Groza, smiling from ear to ear, and he says: ‘You can miss ’em, son, you can miss ’em.’

“Lou was a great guy – and what a great guy to work with. The decision that [then Browns coach Blanton Collier] made to keep Lou as my coach so I learn the finer points of kicking helped me to lead the league in field goal percentage during my rookie season.”

On Oct. 19, 1975, Cockroft kicked five field goals in a game against the Denver Broncos. Cockroft’s achievement was bittersweet, however, as he missed two other field goals that day in Cleveland’s 16-15 loss.

“I knew going into that game that I was close to breaking the NFL record for most consecutive field goals,” said Cockroft. “And I’m out there in pre-game warm-ups kicking field goals like it was practice. It’s a funny story, but it’s not funny to me. As I was going onto the field in Denver, the announcer for the game – and I think he did it for a purpose – said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, if Don Cockroft makes this field goal, he’ll set a new NFL record for most consecutive field goals.’ And I missed. My holder, Mike Phipps, looked at me and said, ‘Don, I knew I should have called time out. Your eyes were so big.’

“I kicked five field goals that day and had tied the NFL record for consecutive field goals, but we lost the game by one point, as Jim Turner knuckleballed a 53-yarder through the uprights to win the game. I still can’t believe it.”

In general, Cockroft does not believe that the opposing team gained an advantage by calling a timeout prior to a kick in order to ‘ice’ him.

“Fortunately, I tended to make kicks in those situations, and I almost looked forward to them,” Cockroft said.

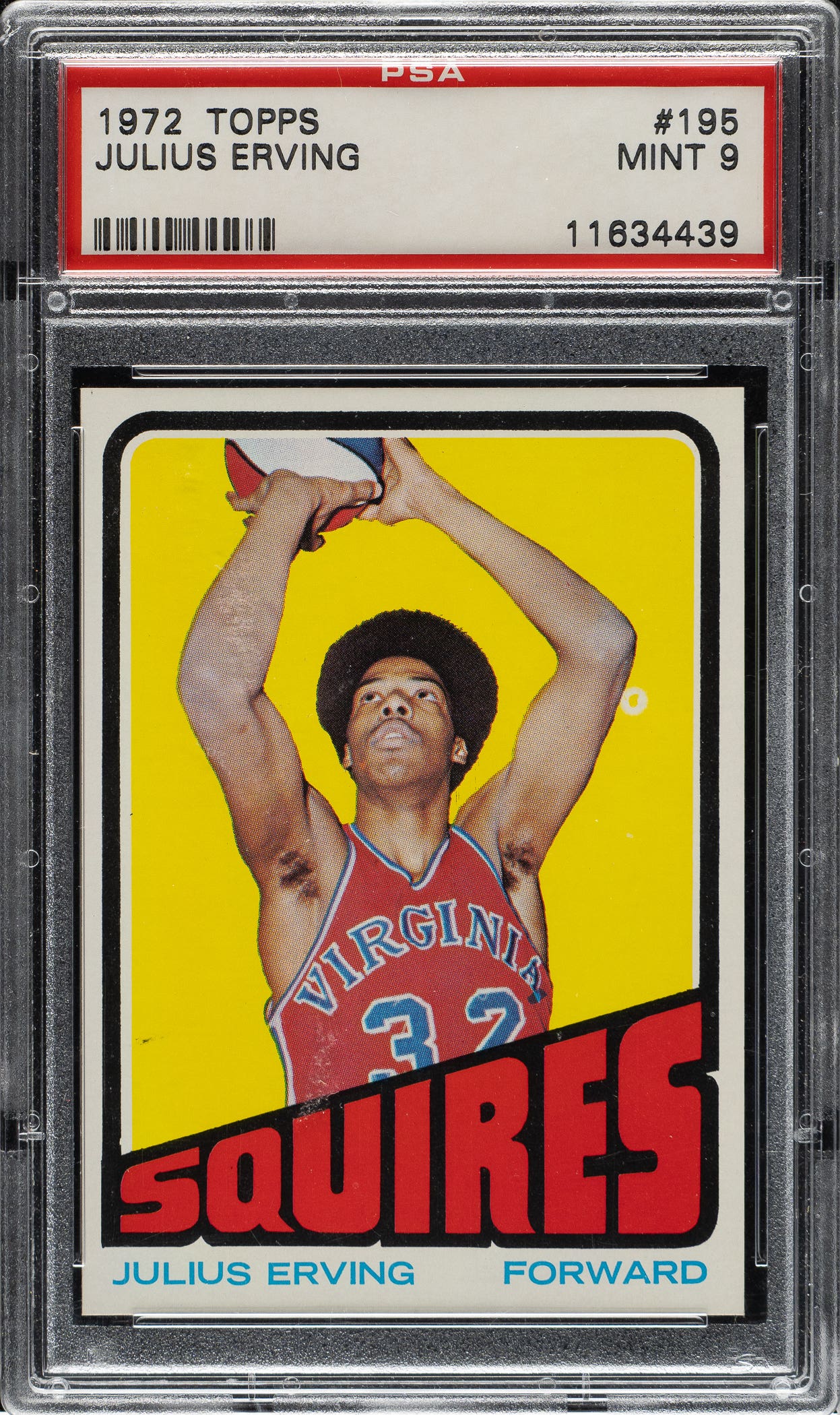

More than 30 years after he retired from the NFL, Cockroft still gets football cards to sign in the mail from autograph collectors.

“I probably get about four or five cards a week in the mail to sign,” said Cockroft. “The one I see the most is my 1977 Topps card, where Charlie Hall is blocking for me. The other one is the 1979 Topps card, where I look a little ticked off. I had probably just missed a field goal or something.”

Like many collectors from that time frame, Cockroft did not keep the cards he collected in his childhood.

“I’ve got a player card story that will make you sick,” Cockroft said. “When I was young, in the sixth and seventh grades, I collected baseball cards. In the seventh grade, we moved from Delta, Colo., to Fountain, Colo., where I ended up for most of my high school career. I had two boxes full of baseball cards sitting on my lap. Now, we’re talking Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, all the greats. Two, two shoeboxes full of them.

“My brother was older than I was, and he could drive. He and I were the last ones to leave the farm, heading to Fountain, where we’re going to live. The car was totally packed, and I’ve got these baseball cards in their boxes on my lap in the passenger seat. And my brother said, ‘Don, we don’t have room for those. Get rid of those. Throw them in the barrel.’ I said, ‘No, I can carry them.’ And he said, ‘No!’ He’s my big brother, so I listened to him. I remember throwing Mickey Mantle, all those cards, in the 50-gallon drum, and they were gone. Now, that hurts a lot!

“Back then, you’d get the cards and the bubble gum. I wanted the bubble gum more than anything. None of them were signed, but I had all those guys. I probably had Mickey Mantle’s rookie card.

“I did get to meet Mickey Mantle right after I got out of football. I was in the oil and gas business, and we were at a trade show and I was giving away an actual football that we used as a prize to get people’s business cards. In the next booth over was Mickey Mantle, representing some insurance company. And I said, ‘Forget this, I’m not giving this football away.’ I went over to him, and he signed the whole side of the football ‘Mickey Mantle.’ And I gave that football to my son. We gave the winner another football.”

Cockroft remains very appreciative of his opportunity to play in the NFL.

“If you work hard, you’ve got God-given talents, try to maximize those, learn what those might be. And honor God in what you do. Then you’re not going to have any regrets, whether it’s success or failure,” said Cockroft. “I also took away the camaraderie, the sense of team, everybody working together. I could be here for an hour talking about what I took away from football.”

Cockroft believes that the 1980 Browns season was, from a fan’s perspective, one-of-a-kind.

“I pray and hope that the Browns will someday win a championship,” said Cockroft. “But it will never be what it was during my era because of the connection between the players and the fans. Today, players are too untouchable. It wasn’t that way, back then.”

The website for Don Cockroft’s book, The 1980 Kardiac Kids: Our Untold Stories is www.thekardiackids.com.

John McMurray writes a monthly column for SCD. He can be reached at jmcmurray04@yahoo.com.