News

Stepping into Babe Ruth’s shoes

Some might have regarded the assignment as Mission Impossible, might have wilted under the white-hot spotlight. After all, what act in the history of baseball – perhaps in the history of sports – could be tougher to follow than Babe Ruth in The House That Ruth Built?

But George Selkirk knew exactly what he was up against. He understood that succeeding his idol and the idol of millions of other baseball lovers would be as daunting as trying to hit a fastball with a twig because each time he stepped into the batter’s box he would be competing against two opponents – the pitcher and Ruth’s legend. But, after toiling in the minors for eight years and after batting .313 with 38 RBI in 46 games following his call-up to the New York Yankees in 1934, Selkirk believed he was ready for the challenge.

Yankees Manager Joe McCarthy believed he was ready, too. That’s one reason “Marse Joe” agreed with the front office decision to jettison the fading, overweight, soon-to-be-40-year-old Ruth before the following spring training. When Selkirk arrived in Florida for his first camp as the Yankees starting right fielder, McCarthy pulled him aside and talked to him about “being your best self.” The Yankee skipper walked away from that conversation even more convinced the Canadian-born slugger had enough intestinal fortitude to handle the task.

Not lacking for confidence, Selkirk told McCarthy: “If I’m going to take his place, I’ll take his number, too.’’

So, Ruth’s hallowed No. 3 was placed on Selkirk’s back that season, like a bull’s-eye, for all the world to see.

“Instead of being just another outfielder, I was expected to make the fans forget about one of the greatest players in the history of the game,’’ Selkirk reflected years later. “Did I worry? Well, I tried not to. Ruth, you know, had always been my baseball hero, but never had I thought I would be taking his place.”

Rather than fold, Selkirk flourished. In his first full season in the Bronx, the muscular, 6-foot-1, 190-pound left-handed batter hit .312 with 11 homers, 29 doubles and 94 runs batted in, second only to the team’s leading run-producer, Lou Gehrig. The following year, Selkirk clubbed 18 homers, drove in 107 runs, batted .308 and earned American League All-Star honors as the Yankees won the World Series.

He would go on to have a solid but underappreciated nine-year, big league career – all with the Yankees – batting .290 with 108 homers and 576 RBI in 846 games while helping the Bronx Bombers win five Fall Classics and six pennants. Although he didn’t “replace” Ruth – who could? – he did become the best George Selkirk he could be, winning as many Series titles in pinstripes as the Bambino did, and earning the respect of his Hall of Fame manager while establishing himself as one of the greatest Canadian-born players.

“Selkirk was one of my favorite players, taking over Ruth’s spot at bat and in the field,’’ McCarthy said of the outfielder who became known as “Twinkletoes” for his distinctive, light-footed running style. “George was under heavy pressure that first year, but he came through brilliantly. No player ever had a tougher assignment.”

Interestingly, Yankee fans took it relatively easy on Selkirk, something they didn’t do when two of his proteges, Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris, were in the early stages of their Yankee careers. The Mick was subjected to Bronx jeers off and on for nearly a decade after he succeeded Joe DiMaggio in centerfield in 1952. The tide finally turned in 1961 when they began to appreciate Mantle’s baseball greatness while turning their vitriol toward Maris for having the “audacity” to break Ruth’s single-season home run record.

The fans rarely booed Selkirk for his fielding miscues and for not putting up “Ruthian” numbers at the plate. He often wondered why he was given a pass by the “bleacher creatures” at Yankee Stadium. Selkirk’s teammate, center fielder Ben Chapman, offered a humorous explanation, quipping, “They’re too busy booing me to pay any attention to you.”

Selkirk was born in Huntsville, Ontario, on Jan. 4, 1908 and moved with his family to Rochester, N.Y., when he was about 7 years old. Selkirk’s father had been a carpenter and stone-cutter, and when a fire destroyed his sister’s home in Rochester, William Selkirk made the three-hour trek from Canada to help build a new house for her. The elder Selkirk brought his wife and kids with him, and he decided to keep them there after the house was constructed.

Young George excelled at all sports, including wrestling, in which he won a sectional title in his weight class during his senior year of high school. Interestingly, years later, while with the Yankees, Selkirk reportedly became the only player capable of wrestling the Herculean strong Gehrig to a draw in friendly clubhouse matches.

Baseball, though, would prove to be Selkirk’s meal ticket. He wound up signing a contract with Rochester’s International League team as an 18-year-old after wowing scouts with a stellar performance in a semi-pro game. “One of his good friends was pitching against him, and before the game, George went up to him and said, ‘Look, there’s a scout in the stands, so I need to make a good impression,’’’ Selkirk’s 92-year-old cousin, Chuck Starwald, told me in a 2016 interview. “His friend said, ‘OK, I’ll give you one shot. The first pitch every time up will be right down the pike. If you miss it, tough luck. You won’t be receiving any more gifts.’ I guess George didn’t miss much that day, because the scout signed him to a contract.”

Selkirk spent the next six seasons in the minors, and although he put up some impressive numbers, he didn’t land a spot on the abundantly talented Yankees roster until he was 26 years old. His opportunity came not long after center fielder Earle Combs crashed into the concrete wall at St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park on July 24, 1934. Combs, a future Hall of Famer, broke his left collarbone and fractured his skull, sidelining him for the season. The Yankees decided to call up Selkirk, who was hitting a robust .357 for their Triple-A affiliate in Newark.

He didn’t make his major league debut until nearly three weeks later in a doubleheader that was billed as Ruth’s last game at Boston’s Fenway Park. Selkirk played both games in right field, while Ruth was stationed in left. In the nightcap, the Babe was replaced in the later innings by Sam Byrd. The thunderous ovation Ruth received from the overflow crowd of 46,000 made an indelible impression. “The crowd was clapping and cheering for the Babe,’’ Selkirk recalled. “I just stood there and then I realized I had taken off my cap and I was clapping my hands, just like those people in the stands. It was something that came from the heart. I felt a little ashamed of myself, thinking that I was just a busher, and then I looked around and there were the rest of the Yankees players, and they were doing the same thing.”

The next season, Ruth finished his Major League Baseball playing career where it had started, in Boston, but with the Braves rather than the Red Sox. He stumbled to the finish line with a .181 batting average and six homers in 28 games in his shortened final season.

Selkirk, meanwhile, met the challenge of succeeding the Babe head-on. He batted over .300 five times and twice drove in more than 100 runs in a season. In 1936, he became the first Yankee to homer in his first World Series at-bat. His best season would come three years later, when he clubbed a career-high 21 homers, drove in 101 runs, scored 103 runs, batted .306, stole 12 bases and had a .969 on-base-plus-slugging percentage.

By 1941, he was reduced to a reserve role and a year later he enlisted in the United States Navy, where he rapidly rose to the rank of Ensign. Upon his return from World War II, the Yankees released him, but he would continue to contribute to the organization as a minor league manager in Newark, Binghamton and Kansas City. During his seven seasons, he helped nurture several stellar prospects, including Hall of Famers Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford and Mantle.

After a falling out with the Yankees in 1952 over the promotion of two players he believed weren’t ready for the majors, Selkirk spent three seasons managing in the Milwaukee Braves farm system before becoming player personnel director for the Kansas City Athletics, where he discovered future Yankee Maris. In 1962, he took over as general manager of the new Washington Senators. Despite a draconian budget, the Senators improved their record six seasons in a row under Selkirk, but he was fired in 1968, and retired to Florida with his wife, Norma.

Selkirk’s finest moments included an eight-RBI game, a walk-off home run in the 16 inning, and four homers in four consecutive at-bats against the same pitcher over two games. His five World Series rings resulted in him being called Canada’s “Mr. October” and earned him induction into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame as a charter member in 1983. His slugging for Newark, Rochester and Toronto, as well as his managing success in Newark, landed him a spot in the International League’s Hall of Fame in 1958.

Selkirk’s most significant contribution – one still being felt today – may have been his suggestion to install six-foot, cinder paths in front of outfield walls. These “warning tracks” greatly reduced the number of wall-banging injuries and extended the playing careers of many.

But when he died at age 79 in 1987, the obituaries didn’t focus on his suggestion or his catchy nickname or his fistful of World Series rings. Instead, George Alexander Selkirk was remembered for being the guy who succeeded George Herman Ruth. It was an impossible task that he handled quite well.

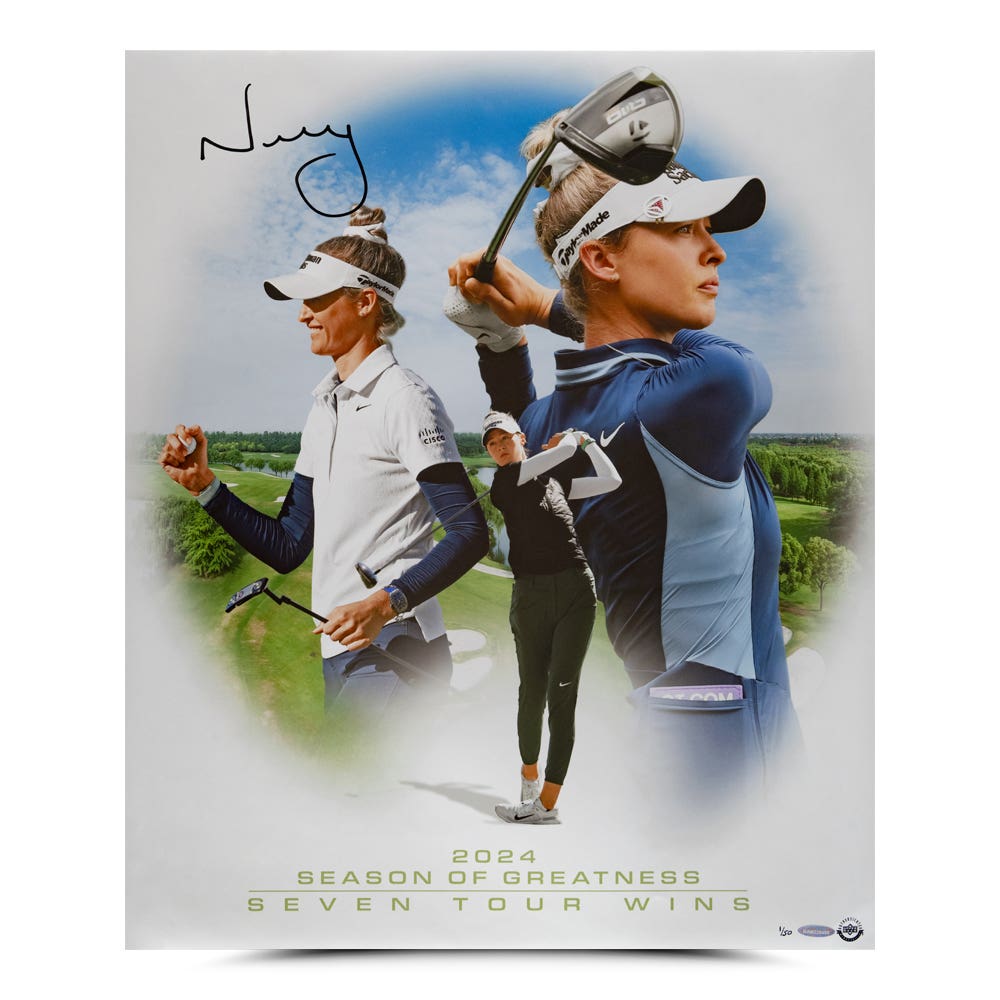

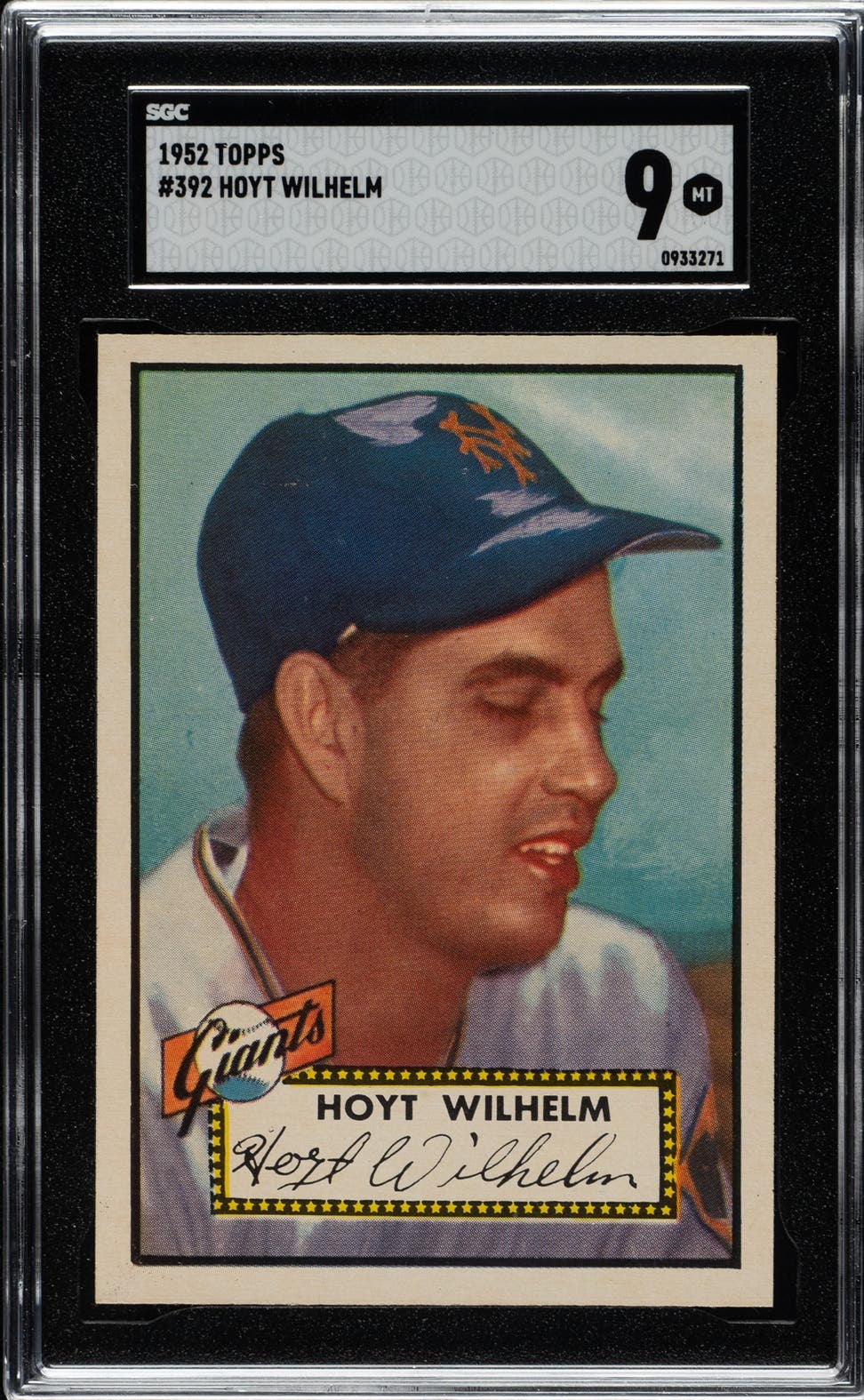

A look at George Selkirk collectibles

In December 2016, a Yankees pinstriped jersey worn by George Selkirk during the 1939 season fetched $22,796 at an event run by Grey Flannel Auctions. Interestingly, the uniform, featuring Babe Ruth’s old No. 3 on the back, sold for more than double the $10,000 salary Selkirk earned while wearing it for the Bronx Bombers that summer.

Six months before that jersey sale, a game-used Selkirk Louisville Slugger bat from the late 1930s sold for $8,365 in a Goldin Auctions auction. But there was a catch: The bat featured a Lou Gehrig autograph that was graded an 8 by experts from PSA/DNA Authentication Services.

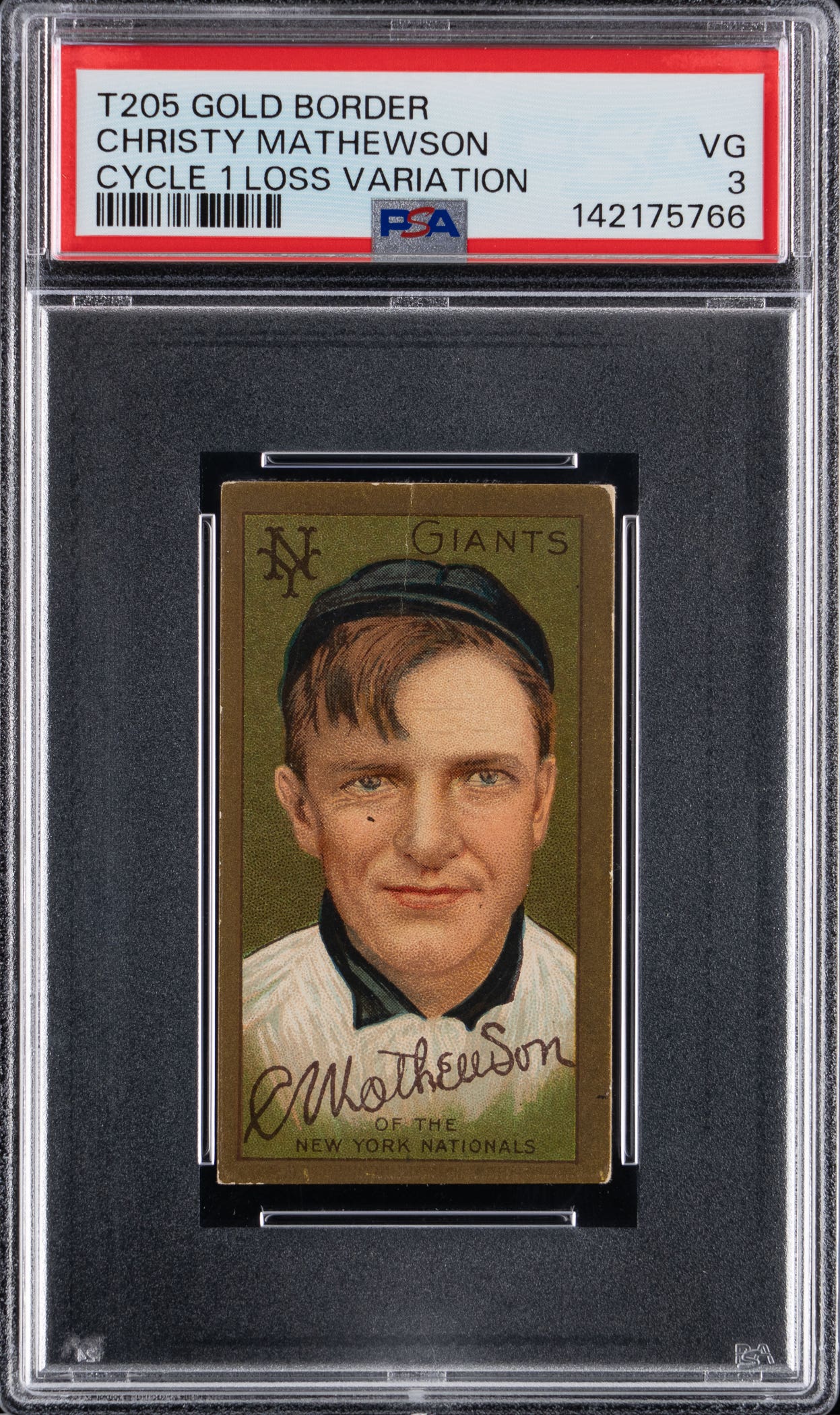

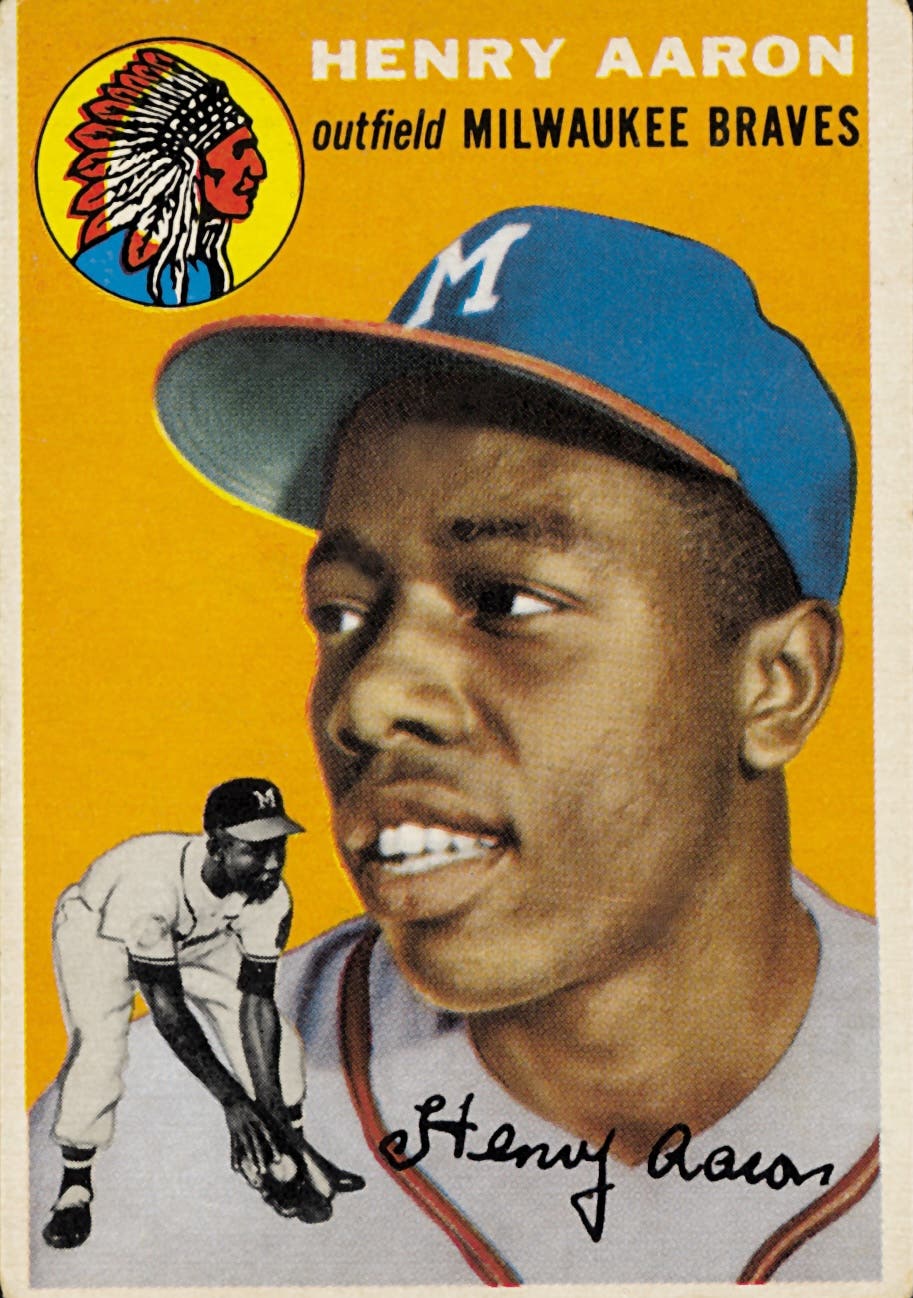

Most Selkirk collectibles, though, can be had for a fraction of those costs. His Conlan TSN No. 388 card is just $3, while his 1935-36 Diamond Stars No. 88 ranges from $10 to $89. Depending on condition, you can purchase his 1940 Play Ball Set No. 8 card for anywhere from $20 up to $250.

Authenticated Selkirk signatures on 3x5 index cards run between $40 and $45. His autograph on the 2006 Legacy “When It Was a Game” cards are somewhat pricier, available from $80 to $180. Steiner Sports featured an 8x10 black-and-white photo of Selkirk following through on a swing, signed in blue Sharpie, for $175.

Scott Pitoniak is a nationally honored journalist and best-selling author of more than 25 books, including the recently published, “Remembrances of Swings Past: A Liftetime of Baseball Stories,” available in paperback and on Kindle at amazon.com. You can reach him at spitoniak@aol.com or on twitter @scottpitoniak.