News

Catching up with hobby icon Sy Berger

By T.S. O’Connell

So, consider Sy Berger, the man who helped to conjure up designs for some of the most revered baseball cards extant. The man who captained a barge loaded with hundreds of cases of 1952 Topps high-numbers destined for the floor of the Atlantic Ocean and a much-reviewed page in the sports collecting history book.

Sy Berger, friend and confidant of hundreds of ballplayers, the man whose job was (in part) comprised every young man’s dream: hanging around in major-league dugouts and befriending the greats of the game. The man who rose through the ranks at Topps from a summer internship to vice president of licensing has always been the first to concede that he may have had the very best job in the world.

“I’ve had 50 years, and I don’t think anybody who works for a living has enjoyed doing what they did more than I did. For me it was the ideal thing,” Berger said in an interview at the All-Star Game in 2000 in Atlanta. “I was just a young kid when I joined the Topps family, and they knew I was a sports nut, and they just let me go. No strings, no binders, just go do it. They let me express myself, design wise, what we put in the cards. As far as the relationship outside the cards, how to negotiate with the ballplayers, nobody ever told me how to do it, they just said, ‘Go do it.’ And I did it.”

For Berger, it’s all been about the people involved in the business/sport. He has had relationships that continue even to this day with multi-generation baseball families like the Boones and the Bells. “I’ve seen Ray, Bobby, Brett and Aaron Boone. In my wallet I carry a 1985 Topps Father/Son card of Gus and Buddy Bell,” said Berger. “I started that father/son thing (the card subset, not the overall idea) and I saw all these generations. Gus Bell was a great guy. I loved Gus, and Buddy is a wonderful guy.”

Perhaps Berger’s most famous relationship is with Willie Mays, who was known to be pretty picky when it came time to reviewing his latest baseball card. “One of my favorite memories in those early years was Willie Mays, back in 1951, he was just a kid and I met him in the locker room,” Berger recalled. “Willie was just a nervous kid, and since it was my first trip to a big-league locker room, I was nervous, too. As Willie says, he was scared and looking for a friendly face, and I walked in. I am probably one of his best and oldest friends, and I am his representative. Not by choice, but because he said, ‘Please do this.’” (Even in the years following this interview, Sy and Willie have continued to team up most years for the annual pilgrimage to Cooperstown for the Hall of Fame incuctions.)

From the Polo Grounds it was only a short hop to the Bronx and Yankee Stadium, where Berger confronted a whole different problem. “In the Yankees’ clubhouse, I befriended Jerry Coleman. He was the player rep, and it was quite a thing to get those guys to sign, because they were the world champs.

“Mickey Mantle and Whitey Ford were young guys then, and I sort of gravitated to them. It was a good experience. They had their names in the box scores every day, and now you are walking around among them. Later on, I became a fixture.”

And along with mixing with the most famous names in baseball history, he also rubbed elbows with some memorable names from the world of collecting. “I designed the first cards, and I told Woody Gelman, ‘This is what I want,’ and Woody would sketch it. And that’s the way we worked.

“That was probably the first eight or nine years, and then we got professional designers. I designed that 1953 card and was instrumental in getting the painting done. We had a guy doing those paintings a mile-a-minute. A little off-the-wall guy named Moishe. He did the bulk of the cards.”

Berger is also justifiably proud of his work in signing the famous, and just as often the not-so-famous, to those exclusive Topps contracts that guaranteed every player a small stipend or a shot at the Topps catalog to turn the royalty money into a consumer durable or maybe a transistor radio. But his name comes up almost as frequently from some of those who got away, at least for awhile. But few players managed to avoid signing on the bottom line for Sy. Sooner or later, he got to just about everybody.

One of the most famous MIAs was Stan Musial, easily the most prominent player in the National League, who somehow turned up missing in the classic Topps sets from 1952-57. What seems startling in the year 2000 probably wasn’t too much of a big deal back then, though it almost certainly left a lot of youngsters wondering where Stan went as they opened their nickel packs.

“Stan did not want to sign for any more cards,” Berger remembered. “Al Fleischman was the PR guy for Auggie Busch. Fleischman approached me for a big contribution to charity. I said, ‘I can’t do it.’ I said, ‘You get me Musial and we’ll give you a contribution.’”

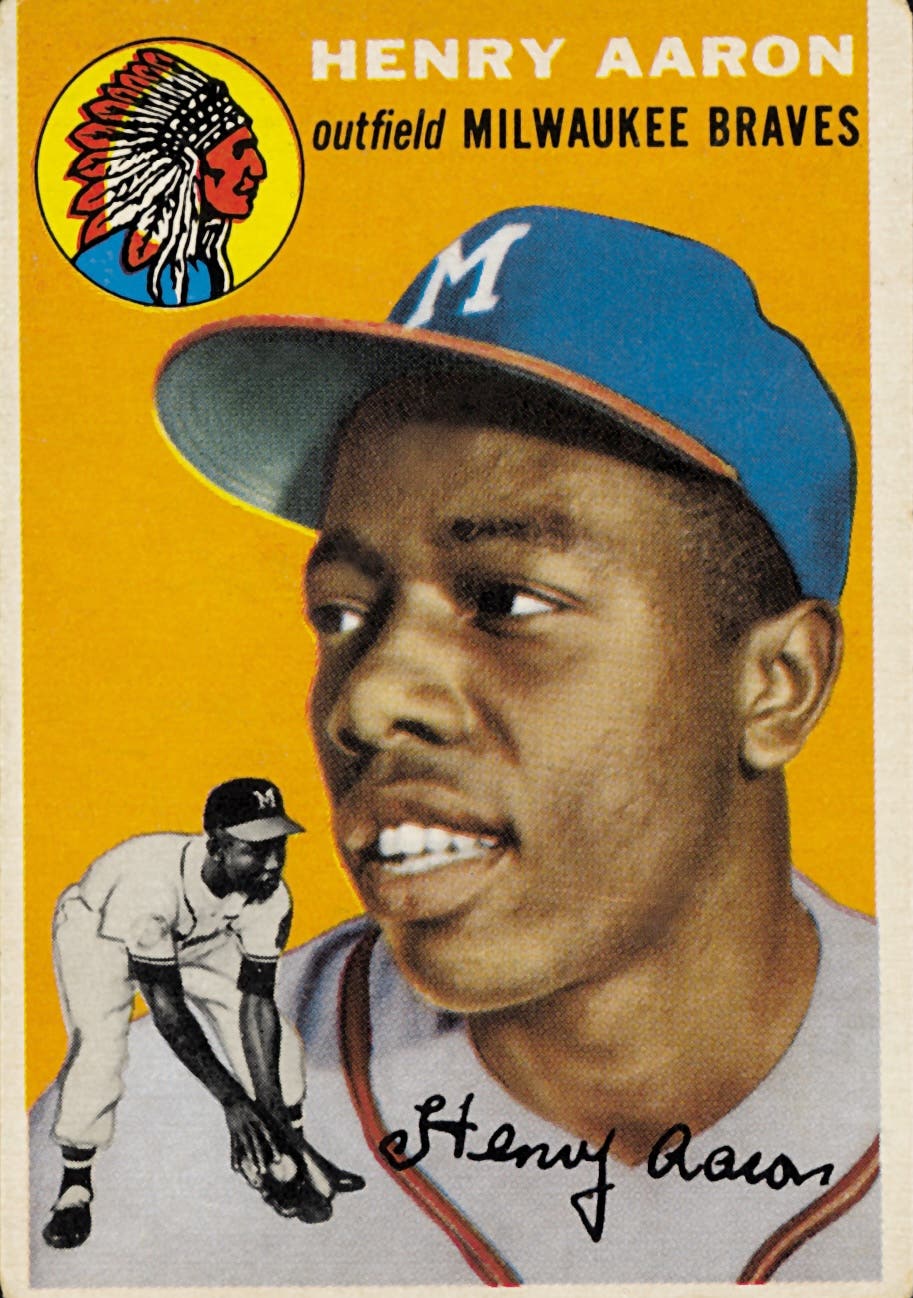

Ted Williams didn’t have a Topps card in 1952 and 1953, but Berger pulled off another big one the following year. “One of the best things I ever did was when I got Ted Williams included in the 1954 Topps set,” said Berger of the man who graced the first and the last card in that set. “It was the only time an individual player received more money for his appearance on cards. We used him for promotional purposes as well.

“That was such a great thrill, because I was a Red Sox fan. It was also a coup for Topps, because the guy who was signing players for Bowman was also a good friend of Ted’s.”

The game’s other marquee player at the time, Joe DiMaggio, was all but ready to retire by the time Topps came upon the baseball card scene in 1951. “We only approached DiMaggio once, and that was when he was a coach for the Oakland A’s,” Berger recalled. “He said he might do it for $1,500, but we told him we can’t increase the payment, and he turned us down. Later he came to New York and wanted to get a television at wholesale, and I took care of him.”

The story about Topps and Maury Wills winds up being part truth and part urban legend. For the uninitiated, Topps supposedly snubbed Wills when he was in spring training, then was unable to get his signature on a card contract once he had ascended to his position as one of the pre-eminent base stealers of his time. We’ll let Mr. Berger tell it:

“I had a guy working for me who was a former minor-league player, Turk Karam, who was a scout. He had access to clubhouses and knew a lot of players,” recounted Berger. “He did a good job for us. I always had a standing argument with him. I always said, ‘Turk, sign ’em, don’t scout ’em. If the club will give them a uniform to wear, we’ll give them the contract for five dollars.’

“He was quite a guy. “He’s at spring training. I said, ‘Sign everybody.’ There was a guy named Wills there. Detroit had brought him in conditionally from the Dodgers. I get the contracts back and there’s nothing there about Maury Wills. No contract, no nothing. “I called him and said, ‘What’s the matter? Where’s Wills?’ He said he was told by the Detroit guys, friends he knew and coaches, that Wills would never make it. So he didn’t sign him. I argued with him.

“Fleer was trying to get in at that time, so they signed Wills. They were signing guys on each club, giving guys $750 to try to steer teammates away from Topps to sign with Fleer.”

But Berger at least dispels the notion that the Dodger shortstop was ‘mad’ at Topps. “Wills and I became great friends. He was the first guy to come over and see me at spring training this year. He was never mad at Topps” (confirmed by Wills in an interview in 1999 with SCD).

A submerged fortune

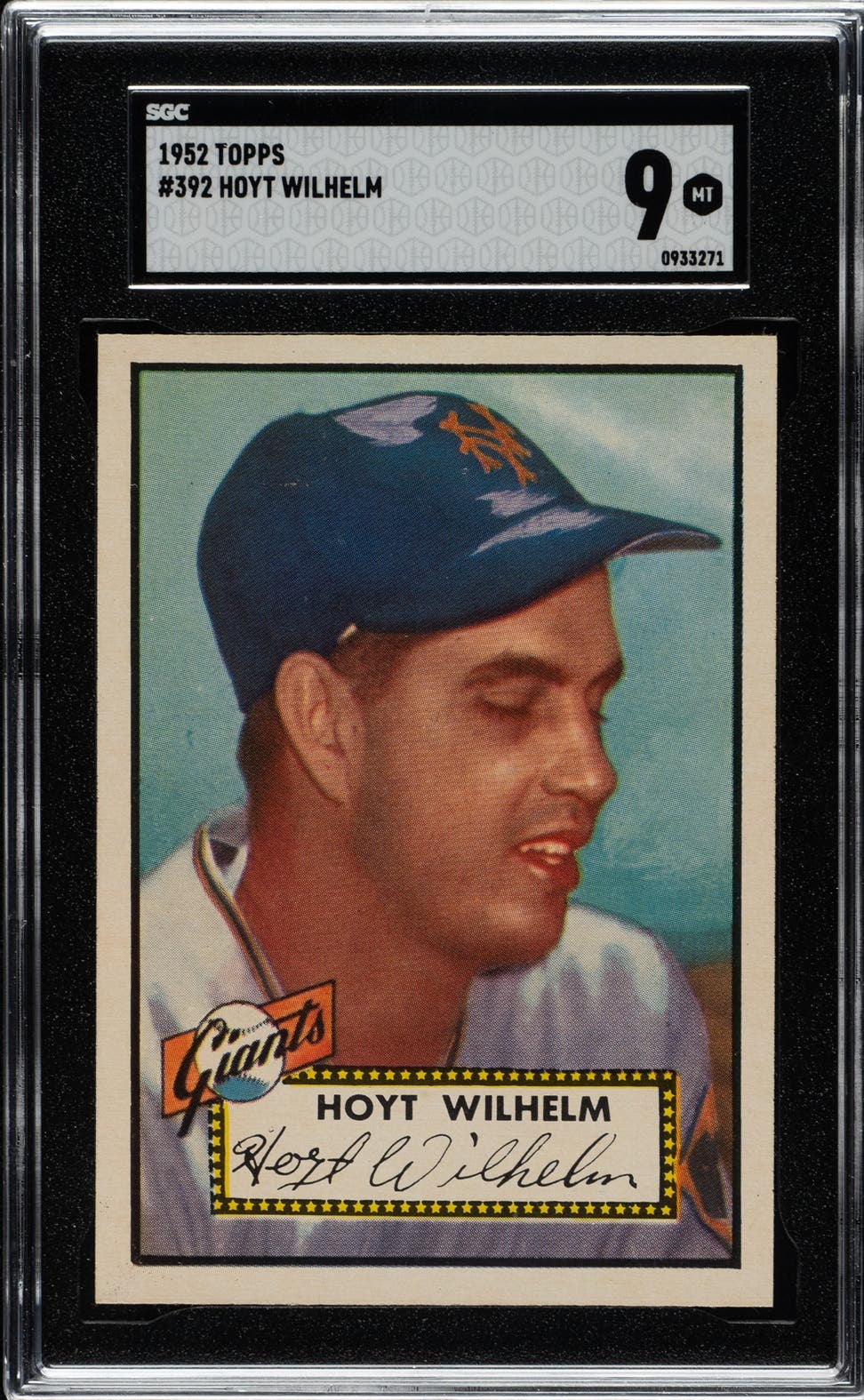

Aside from his dealings with Hall of Famers, Berger might be best remembered for a bit of mischief on the high seas. We refer, of course, to the unceremonious dumping of hundreds of cases of leftover 1952 Topps Baseball high numbers into the Atlantic Ocean sometime around 1959 or 1960. It is a story that begins almost a decade earlier when Topps took the unprecedented step of printing a late-season series of cards.

“The 1952 Topps cards were selling like we were giving away gold. I went to J.E. Shorin (one of Topps’ founding brothers) and said, ‘What do you think about a second series?’ He said he didn’t know.

“He asked if I could get it out quickly. Little did we realize that by World Series time, baseball cards were not the feature. Mantle and Mays were in that series and a lot of players whose pictures we did not use because of the Bowman/Topps contract wrangle. I had gotten the contracts signed.

“We turned the product around real quickly,” said Berger, something of an understatement, since the backs of some of the 1952 Topps high numbers include statistics and some game accounts from the 1952 season itself. “That was numbered 311 to 407. And it didn’t sell,” Berger continued.

Obviously, a late-season printing was a gamble. “We used to start our first shipments March 1,” Berger noted. “High numbers were always printed in shorter numbers, I would say at least 50 percent of the other series. “The 1952 high series went all over the country, everybody was happy to buy it, but when it didn’t sell that was when we found out what returns meant. It was clogging this warehouse in Brooklyn.”

Topps’ ultimate solution probably doesn’t surprise experienced collectors, who understood that Topps officials never stockpiled any older cards. It was a time when baseball cards were treated as a consumer product, not as a collectible, and Topps historically moved out its stock of each year’s cards to make room for the next.

“We never kept any cards except that those we pasted into books,” Berger recalled. Even those were eventually disposed of, this time in a record-setting auction of much of the company archives by Guernsey’s in the summer of 1989. Much of the proceeds from that sale went to charity, with Berger earmarking $100,000 for the fledgling Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) that aids former ballplayers who are down on their luck.

But back to those 1952 high numbers. Faced with a bulging warehouse of cards now almost 10 years old, Berger, the preeminent card designer, licensing agent and contract hound, now switched hats and tried his hand at actually selling baseball cards. Wholesale. Really, really wholesale.

“Around 1959 or so, I went around to carnivals and offered them for a penny a piece, and it got so bad I offered them at 10 for a penny. They would say, ‘We don’t want them.’

“I couldn’t give them away. So we said let’s get rid of them. We decided to dump them in the ocean.” Topps had stored those 1952 Topps for eight or nine years. According to Berger, these were all cut cards.

“They were put in boxes. It took three garbage trucks. I would say 300-500 cases. All high series of 1952 Topps. “I found a friend of mine who had a garbage scow and we loaded the three trucks-worth on the barge.” It was tugged out by a tugboat, with Berger on board to supervise the undertaking, such as it was. “I was out there with it. Opposite Atlantic Highlands, a few miles out.”

The cases were stacked on the center of the barge, and a switch was thrown and those (now) precious cards were consigned to the deep. “And that was the end of it,” said Berger. “Whoever thought that they would have the kind of value that they would have?”

Attaching a dollar number is essentially impossible, or at least unwieldy, but one could make a good argument that our pile of cardboard on the ocean floor would now be worth tens of millions of dollars. The exercise runs afoul of hypothetical quicksand, because if the cards hadn’t been dumped, the high series wouldn’t be so valuable 50 years later. You get the idea.

Certainly, captaining that ill-fated barge represented a sharp divergence of duties for Berger, but he had many duties at Topps outside of those for which he is most well known. “I did many things besides baseball. I brought the football in. I brought basketball in. And I did all the licensing for years and years,” he pointed out. “I was part of the team when we signed Elvis, the Beatles, Michael Jackson, New Kids on the Block, ET, Charlie’s Angels, Star Wars, Batman and others. I made all of those deals and contracts.”

His role as vice president of licensing also brought him up against a man who would almost single-handedly reshape the world of sports cards: Marvin Miller. “Marvin did a marvelous job for the players. Marvin and I were very dear friends. He was brilliant and he was doing his job. I admired him. It resulted in us having to be more creative and do a better job. I didn’t look upon him as an adversary.

“We knew there would be a players’ association. I knew we had to deal with it,” he continued. “The first contract was negotiated with J. E. Shorin. It was very adversarial. He and J.E. did not get along.”

These are a few of his favorite things

Berger’s favorite card design is 1954 Topps, and he also likes the Sporting News and Sport magazine All-Star cards, combination pictures, coach cards, cards with the Little League pictures, and the idea of “In Action” cards. “I had advocated action photography for three or four years. They wouldn’t hear of it. And I had two big file cabinets full of action pictures. They did a survey and found out that kids wanted action pictures. They came to me in December and said, ‘Where are we going to get color action pictures?’ – and I had them.”

That shouldn’t have been a huge surprise. He had a pretty good track record of figuring out what all those youngsters across America wanted in a baseball card.

Lucky for us.

MORE RESOURCES FOR SPORTS COLLECTORS

- Get current market values for 400,000+ baseball cards issued between '81 & '09

- Get the Ultimate Yankee package

- Interact with other sports collectors in Tuff Stuff's online forum

- Sign up for your FREE email newsletter from Tuff Stuff

- Read the latest 7th Inning Stretch Blog from Tuff Stuff Editor Scott Fragale