News

RETURN TO DODGERTOWN: Historic Spring Training site evokes nostalgia, serves as setting for new baseball novel

Over the course of my almost 30 years writing Stadia Collector features for SCD, I’ve had the opportunity to mention Dodgertown, the most famous Spring Training site, a few times.

One reason could be that it’s literally in my backyard in Vero Beach, Fla., where I reside part time. The other reason is because it’s so dang beautiful. But when I decided to write a novel with Dodgertown as the setting, it raised it to a whole new level for me.

Dodgertown was built for the 1948 Spring Training season on the site of a decommissioned World War II naval air base in the then-nondescript Florida town of Vero Beach. Dodgers General Manager Branch Rickey saw its potential as a college-type campus where he could house players of all colors and ethnicity (Florida was strictly segregated into the 1960s).

The campus was self-contained, with multiple training diamonds, batting cages, etc. There was also tennis courts, a swimming pool, a golf course, a movie theater and other amenities to serve those players who otherwise could not move about comfortably in the surrounding area. Holman Stadium, a gem of a ballpark named for Bud Holman, the local businessman who brought Rickey to Vero Beach, opened in 1953.

Over time, Dodgertown would be regarded as the gold standard for Spring Training venues, receiving upgrades during the long O’Malley family regime and serving as the Dodgers’ training base for years after the big club’s move to Los Angeles. Its fame as a winter time site drew thousands of fans and tourists every year and led to the tremendous growth of Vero Beach itself.

But by the early 2000s Dodger ownership decided that having a Spring Training base on the opposite side of the country wasn’t financially feasible, especially because the original Brooklyn fan base was dying off and their current fans had little desire to travel cross country to another warm weather site. So, Dodgertown ceased to exist as an MLB Spring Training location in 2008, with subsequent efforts to lure another team to take the Dodgers’ place proving fruitless.

A NOSTALGIC FEEL

I first visited Dodgertown in the early 2000s, when I flew to Vero during a February break from school to see my parents, who had purchased a condo in a nearby retirement community. Of course, I immediately fell in love with the place. It’s not just that I was lounging under swaying palm trees with the knowledge that it was freezing back home in Connecticut; the complex had a nostalgic feel to it, with the “streets” (really paved golf cart paths) named after Brooklyn Dodger greats and baseball-style globe lamps scattered throughout the grounds.

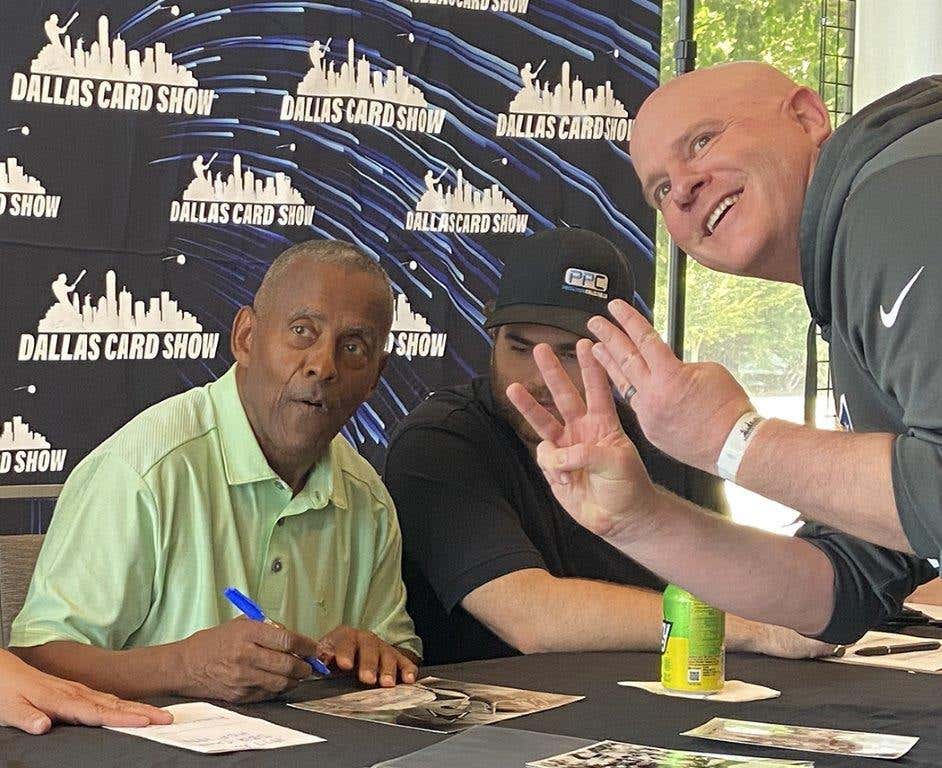

Additionally, there was the general accessibility of everything. One was free to wander about the practice diamonds or stroll into Holman Stadium and take a seat anywhere to watch scrimmages, drills or whatever. Even better, on the practice fields the ballplayers were separated from the fans not by six-foot chain-link fences, but a thin yellow waist-high rope. Thus, obtaining autographs was a breeze and provided real interaction with the players and coaches, some of whom were former Dodger greats such as Maury Wills and, every so often, Sandy Koufax. Then, of course, there was the omnipresent “Mayor of Dodgertown” Tommy Lasorda, who tooled around in a golf cart, stopping here and there to hold court or, if he was in the mood, sign autographs for the fans.

I would visit yearly from then on, even writing about Dodgertown for SCD while also traveling to nearby Spring Training outposts such as Port St. Lucie (Mets), Jupiter (Cardinals/Marlins) and Viera (Expos/Nationals). While gathering information for articles, my wife and daughter were busy cadging autographs, filling their baseballs with signatures and posing for photos. At Dodgertown, this usually took place on the footbridge that connected the practice fields and Holman Stadium, with various players and coaches. It was all low-key and laid-back, quite the opposite of what one might encounter today. My last “Dodger” visit would be in 2008.

From 2009-2018, the facility would undergo different management changes, from the town itself to former Dodger owner Peter O’Malley, in order to keep the place maintained while attracting high school and college teams and tournaments to its grounds. As always, the casual fan like me could just stroll in and check out whatever activities were going on.

Then, in 2019, a deal was struck with Major League Baseball to rebrand the facility as the Jackie Robinson Training Complex and make it a home for MLB-sponsored programs and events, many of them benefiting players from underprivileged areas. This takeover would entail yet another renovation of the grounds and Holman Stadium.

SETTING THE SCENE

As a longtime fan of Dodgertown, I got the idea for my book during a visit to the new complex in June 2020. I wanted to incorporate the nostalgia that is steeped in the place with the story of how and why Dodgertown came to be (it is the only athletic facility included in the U.S. Civil Rights Trail).

So, I arranged a meeting with Rachelle Madrigal, the managing director of the Jackie Robinson Training Complex. She was quite receptive and supportive of the project, and I would call upon her and her staff frequently over the ensuing months for information, such as the opening of a huge indoor training facility named — appropriately — Building 42. (By the way, on the day I visited, a week-long MLB program named RBI was underway, with high school players being tutored by former MLB stars like Fred McGriff, Marquis Grissom, Ken Griffey Sr., and Jerry Manuel).

After much research and consideration, I developed the premise for a novel entitled “The Kid from Dodgertown.” I envisioned it as a modern-day (set in 2012 and 2021) “Field of Dreams” type fantasy involving the 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers that would also teach readers about the history of Dodgertown and its place in the Civil Rights Movement. I also decided that the previously mentioned footbridge would serve as a spirit portal in the story, much like Ray Kinsella’s cornfield. Dodger luminaries Duke Snider, Pee Wee Reese, Joe Black, Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella would serve as the ghostly characters.

Writing this book, from the early stages of research on Dodgertown and the ’53 Dodgers, to the final edits, was a pleasure because once you’ve been to the place, it gets into your blood. And I guess I’m not the only one, because this project gave me the opportunity to interact with some very special people who felt the same way.

DODGERTOWN CONNECTIONS

When you write a book, it’s common to send a preview copy to those who might want to offer what is called “advance praise.” You know, the kind of blurbs you see on the back cover or just inside the dust jacket. So, I put out a few feelers to those I felt had a connection to Dodgertown and whom I hoped would share their ideas. I wasn’t disappointed.

First up was Branch B. Rickey, grandson of the trailblazing executive who signed Jackie Robinson and created Dodgertown and himself a long-time baseball executive who most recently served as president of the Pacific Coast League.

You can imagine my surprise when my email inquiry was answered with a phone call. Not only was Rickey enthusiastic about the project, but he regaled me with stories about the early days and how his grandfather was able to make his vision of a “baseball college” a reality. He chuckled when he recalled the players’ occasional annoyance with the lectures that the senior Rickey would impart each morning before practice with his legendary oratory style.

“But then,” he said proudly, “years later, my grandfather would run into these same men, and they would remind him of the life lessons he discussed that they had put to use in their post-baseball careers.”

He left me with some words that were worthy of his famed grandfather:

“Dodgertown was a dream come true for my grandfather,” Rickey said. “He had envisioned a place that would serve as a training foundation for a Brooklyn Dodger dynasty. But this training base surprisingly became something beyond that, transcending into a realm where not only players’ talents were honed but where lasting bonds formed, commitment and dedication were shaped, and where, steadily, proud histories evolved, all imbued with the magic of that common nucleus, a magic conveyed in Mr. Ferrante’s telling of the tale.”

Next up was Martha Jo Black. I was put in touch with her through Brooklyn Dodgers historian/collector Herb Ross, whom I first met long ago in my early days at SCD. Ross has amassed one of the greatest Brooklyn Dodgers collections and, although he has moved out West, is still active in the Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby 1947 Facebook page. After graciously offering to proofread my manuscript for historical accuracy, he referred me to Ms. Black, the daughter of Dodger hurler Joe Black, the 1952 NL Rookie of the Year and an executive with the Chicago White Sox.

When I contacted Martha about the book and told her that her late father is a key character in the story, she was both excited and moved by the news. She had previously written a book about him and obviously looked up to him as a role model. And although she had never actually been to Dodgertown, she was all too happy to volunteer some thoughts.

She also offered to serve as executive producer if and when the book becomes a movie, and I heartily agreed to this proposal.

“It brought me great joy to read that my father, Joe Black, is one of the Brooklyn Dodger heroes in this tale, where opportunities and dreams come true. Welcome to Dodgertown!” she wrote.

Batting third in this formidable lineup was legendary Dodger lefty hurler Carl Erskine (“Oisk” to the Brooklyn faithful), one of the few surviving players of that era. Once again, Ross was instrumental in getting us together, with Brooklyn Dodgers enthusiast Jim Denny, who is friends with Erskine in his hometown of Anderson, Ind., acting as a go-between.

Denny was able to share the story with Erskine, one of the “Boys of Summer” immortalized in Roger Kahn’s famous book, and he was quite receptive. Erskine had been one of the major players who made the transition to Los Angeles and continued to visit Dodgertown for years afterward as a big-league instructor or participant in the Dodgers’ fantasy camp.

He had nothing but fond memories of the place and had this to offer:

“The one constant over 60 years of Dodger baseball history was Dodgertown in Vero Beach,” he said. ”I trained there as a player and went back many times afterwards. It’s wonderful that someone is keeping the memory of Dodgertown alive.”

Finally, I decided to try to contact iconic broadcaster Vin Scully, who covered the ballclub for pretty much its entire Dodgertown stay. Frankly, I would have been pleased with a snail mail response to my inquiry, so you can imagine my surprise when, on a frigid late winter day, my wife came running into the living room to tell me the Hall of Fame broadcaster was on the phone.

He immediately put me at ease by telling me to drop the “Mr. Scully” stuff, and responded to my description of cold and dark Connecticut with the words, “Well, Paul, it’s a beautiful day here in Southern California!” It was as if I were tuning in to a Dodgers broadcast.

Scully went on to tell me about how, as a rookie radio announcer in Vero Beach, he drew none other than the mercurial Leo Durocher as a roommate, and how in the morning in the “chow line” one could be shoulder to shoulder with a member of the big club, Walter O’Malley or the lowest minor leaguer. Today, one of the streets near Holman Stadium is named for him. Finally, after a long chat, we said goodbye, but not before he left me with this:

“I came to Dodgertown as a rookie broadcaster in 1950 and never missed a game there until the Dodgers left in 2008 … and I left a piece of my heart there as well,” Scully said. “This book will take you for a stroll through a very special place.”

Sadly, Scully passed just a few months later.

And so, after a lot of preparation, “The Kid From Dodgertown” (The Ionian Press) was released in time for Jackie Robinson Day in 2022 with the hope that I’d done the place justice. My readers can be the judge on that.

DODGERTOWN COLLECTIBLES

Now, you might ask, what collectibles are there to be had that relate to this historic venue? Well, they’re out there if you’re willing to do a little hunting. A scan of eBay revealed some interesting items.

First was a 1956 Brooklyn Dodgers letter with the “Brooklyn Dodgers and Affiliated Clubs — Spring Training Camp — Dodgertown, Vero Beach, Florida” letterhead for $40. There are a plethora of vintage postcards of Holman Stadium for as low as $3.99 apiece. These help track the various additions and upgrades to the ballpark that were made during the Dodgers’ tenure.

How about a unused scorecard from the Dodgertown Golf Club? It will only set you back $29.99. Also on the inexpensive side are a fantasy 1948 Dodgertown/Vero Beach license plate at $14.95 and a Los Angeles Dodgers Dodgertown 50th anniversary (1998) game program for $14.99.

Climbing the scale, I found a full-size bat used (and signed) by coach Jim Riggleman that is stamped with both his name and the Dodgertown logo, with an opening bid of $.99 and a commemorative Dodgertown 70th Anniversary pin (2008) for $25.

If you’re into cards, how about a collection of 10 autographed Dodger cards obtained at Dodgertown in 1988, the year the Dodgers won the World Series? These could be had for $124.99.

Or a Rawlings official Dodgertown stamped batting practice baseball? Yours for a cool $299.

Finally, there’s the big kahuna, a collection of signed balls, tickets, programs, etc. (including Tommy Lasorda) from the final Spring Training in 2008 that will set you back $1,999.

You might also ask what I have amassed over the years from my Dodgertown jaunts? Well, quite a lot once I really thought about it. And although some were sold in a downsizing project, I did manage to hold onto some choice personal items: two multi-signed team balls obtained on different visits; personalized photos my wife and daughter took with players and coaches like Maury Wills, Jim Tracy, Paul LoDuca and Milton Bradley; a pair of tickets from an exhibition game at Holman Stadium during that final Spring Training year.

And then, there’s the one I missed on. A couple years ago, my wife and I happened by on the day before we were leaving for home. As usual, we strolled the grounds and ended up in Holman Stadium to see if anything was going on. Well, something was: they were renovating the ballpark.

The playing field was completely torn up and there were tractors and equipment everywhere. You can imagine the Stadia Collector in me thinking a mile a minute. In addition to the work on the field, a crew was preparing to replace the scoreboard out in centerfield to incorporate the soon-to-be Jackie Robinson Training Complex logo. I managed to chat up one of the work crew and he detailed all the changes that were on the itinerary.

“What about the seats?” I asked, as the seats behind home plate, though plastic backs and bottoms had been substituted years ago for the original wood, were pretty beat up and rusty.

“Oh, those are all going,” he said nonchalantly.

“Going where?” I asked.

“Scrap,” he said dismissively. Obviously, he was not a Stadia buff.

“Jeez, I’d really like to have one,” I remarked.

“How come?”

“Just a fan of the place,” I said. “I’d pay you for it.”

“Well,” he replied, “you come back here next week when we do the job and I’ll give you one.”

Alas, we were leaving the next day, and before I could concoct a plan for glomming a seat, my wife was pulling me away, saying, “Uh-uh, honey, nope. Besides, we’re downsizing, remember?” I could have argued, but like Clint Eastwood as Dirty Harry once said, “A man’s got to know his limitations.” Still, I was a little bummed.

When putting together this article, I decided to find out exactly where those old seats had come from, so I contacted Peter O’Malley, who had succeeded his father in running the Dodgers, and who had always been hands-on with Dodgertown. According to Peter, in 1952 his father made arrangements with New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham to purchase some 2,200 portable stadium seats from the Polo Grounds for $1 per chair to use at Dodgertown. Then, in 1960, 6,702 Ebbets Field curve-back, riser-mount seats were sold to O’Malley by Marvin Kratter, who at that time owned the abandoned ballpark, for use at Holman Stadium. In 2015 or so, Indian River County, where Vero Beach is located, replaced the seat backs and bottoms with parts purchased from Camden Yards in Baltimore. So, the seat I could have gotten was a hybrid Ebbets/Oriole Park chair.

In the end, though, when it comes to Dodgertown, it’s more the memories rather than the mementos (though I’m glad to have them) that resonate with me. And although this place has undergone a few name changes since the Dodgers left, it will always be Dodgertown to me.

So if you are ever in the area, a visit to this hallowed site is a must. The Jackie Robinson Training Complex is a gem, harkening back to an important period in baseball — and American — history. It is literally dripping with nostalgia, a feeling I tried to convey in my new book. And, as you have learned, I’m not the only person who feels strongly about it.

Dodgertown has a way of getting in your blood, and if you’re a Stadia fan like me, you’ll never want to leave. Until next time, please stay seated!

— Collectors can contact Paul Ferrante through his website www.paulferranteauthor.com. “The Kid From Dodgertown” can be found on Amazon in paperback and Kindle.