News

Denny McLain Never at a Loss for Words

Denny McLain had one of the best memorabilia collections a person could ask for – major league star or otherwise.

“My wife Sharon, of course, is the daughter of Hall of Famer Lou Boudreau,” the former Tigers great explained. “Lou had quite an extensive collection during his life as a manager and player. Sharon took up on that because it was her mother who did it.”

Add to that McLain’s own items – two Cy Young Awards, his 1968 American League MVP Award and World Series ring.

When signing autographs at baseball card shows, however, McLain doesn’t wear the ring. He says it was stolen by a fellow player. And his most prized trophies – and Boudreau’s? All gone.

“We had a houseful of stuff up until 1978, and then our house burned down,” he said. “Everything we had – Cy Youngs, MVP – everything was destroyed in the fire. Everything.”

No one, however, can touch the memories from his magical 1968 season when he became the last pitcher ever to win 30 or more games, a feat that will likely never be replicated.

The year before, the Tigers finished one game behind the Red Sox on the last day of the season in a wild four-team pennant chase. In ’68, the Tigers charged out of the chute and never looked back. In addition to McLain’s 31 victories, Mickey Lolich chalked up 17 and the offense was led by the likes of Hall of Famer Al Kaline, Norm Cash, Willie Horton and Bill Freehan.

In Game 1 of the Series, McLain took the mound against Bob Gibson, who had turned in one of the best campaigns in modern major league history with a dazzling 1.12 ERA and 22 wins. It continued that day, as he easily beat Detroit.

“The first game, Gibson was the best pitcher I’d ever seen for one two-hour stretch in my life,” McLain said. “He was as good as anything I’d ever seen.”

In Game 4, played on a rainy Sunday afternoon, the Cardinals romped to a 10-1 victory with Gibson again getting the win, while McLain exited in the third frame. At that point, trailing three games to one, the Tigers’ hopes looked like the weather – dreary and dismal.

But underneath, there remained a quiet belief that things would turn out all right.

“No one ever thought we were going to lose,” McLain said. “It was just a matter of fact. Nobody talked about it. We’d been through it in ’67. We almost won it in ’67. There was a certain confidence there and maturity that guys just knew they had to score a couple of runs and everything was going to be fine.”

The Tigers began their comeback with a 5-3 win in Game 5. After yielding three runs in the first, Lolich blanked St. Louis the rest of the way.

Pitching on just two days’ rest, McLain finally got the World Series triumph he longed for in Game 6, turning in a masterful complete-game performance with eight innings of shutout ball until the ninth when the Cards scratched out their only run in a 13-1 loss. Including the regular season, it marked the 29th time that year that McLain had finished what he started, an unbelievable feat compared to today’s standards when pitchers rarely work past the seventh inning.

In Game 7, Lolich took the mound at St. Louis’ Busch Stadium and beat Gibson, 4-1, for his third win of the Series. Having cracked a home run in Game 2, as well, he was an easy selection for World Series MVP.

In Games 5 and 6, Lolich and McLain held St. Louis scoreless for 16 straight innings, and the Cards managed just two runs off them over the final 26 innings of World Series play.

“Mickey and I each pitched on two days’ rest,” McLain said. “He was having the same kind of Series Gibson was. He had the greatest stuff I’ve ever seen, and he consistently threw harder and harder and harder.”

Back home in Detroit, where dozens had died during civil rights riots the summer before, people of all colors danced in the streets.

“An entire city came together,” McLain said. “It was one of those magical moments. Black, white, green, yellow, everybody was in the streets. Not one squad car got burned. Nobody got killed. It was a special time.”

“I Told You I Wasn’t Perfect”

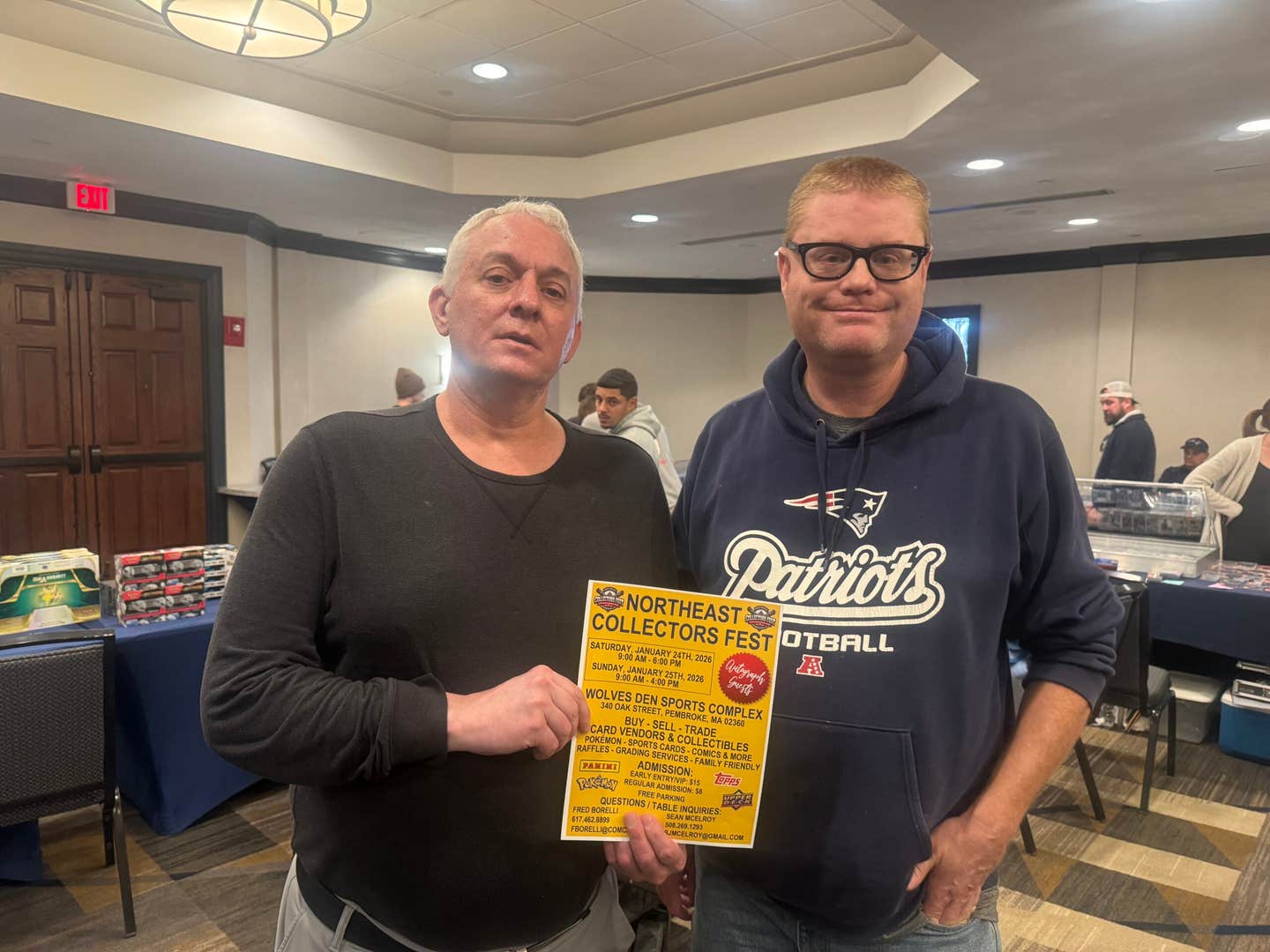

These days, McLain is active on the baseball card show circuit, meeting and greeting fans while reminiscing about his favorite moments in the game.

SCD caught up with the three-time All-Star in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., where he signed copies of his 2007 autobiography, I Told You I Wasn’t Perfect.

He continues to collect memorabilia, mostly for his grandson, who is pursuing a career in medicine.

“He’s got everybody’s autograph in the world that I run into,” McLain said. “He just started college, and he’s gong to be a doctor.”

In September, McLain took part in a celebration for the entire 1968 Tiger team.

“They’ve actually had a number of events this year,” he said. “Jim Northrup is physically unable to attend. Just about everybody else showed up. We were really surprised.”

Always outspoken, McLain said he wasn’t invited to a Tiger fantasy camp or cruise because of his criticism of Detroit’s front office, which he blames for the team’s dismal performance this year. Picked by most experts to not only win the Central Division but breeze their way to the World Series, the Tigers were the biggest bust of the 2008 season by finishing last with one of baseball’s highest payrolls.

“I was in such a minority,” McLain said. “Everybody kept predicting that this was probably the greatest team in Tiger history, that they would run away with the American League pennant. It would be over with by the All-Star break. All I kept asking everybody was, ‘Who the heck is going to pitch?’ ”

“(Dontrelle) Willis is absolutely through. When you give up more hits than innings pitched, you’re in a lot of trouble, and when you give up that many walks versus innings pitched, you’re in a lot more trouble,” he said. “Kenny Rogers, he’s as old as I am. It’s a remarkable thing that he can still get himself a check for $8 or $9 million per year. I respect him for that like you can’t believe. But it really tells you how bad the pitching is in baseball for a guy who hasn’t got anybody out in a couple of years to still be a part of a ball club.

“Verlander, the first couple of years he had some kind of fastball. Well, that fastball kind of disappeared this year. He really has lost his command. If somebody just works with him for a couple of weeks, I think he can put it all back together.”

McLain does believe, however, that Detroit’s future can get turned around in a hurry.

“They’ve got some exceptional players – Magglio Ordonez, who I think is the best hitter in baseball; Cabrera, Granderson. You’ve got four or five guys that if you can build a pitching staff around, you’ve got yourself something special,” he said. “They’re two or three pitchers away from having a solid organization. That doesn’t mean they’re going to win every year, but at least be competitive. This year they weren’t competitive, again. They had no pitching going in. Knowing the disaster, they did nothing.”

Given the care today’s hurlers get, there’s no telling what kind of career numbers McLain might have compiled. In 1968 and ’69, he worked more than 300 innings each, something unheard of with today’s approach to the game.

“It’s an incredible way they manage the kids,” he said. “They certainly take better care of them. For one reason, they have so much money invested in them. That’s what it’s all about – money. There isn’t any other reason to take care of a kid the way they do. At 100 pitches, they panic. Got to get him out! Got to get him out!”

The same is true of valuable relief pitchers such as Mariano Rivera, who rarely works more than one inning, and Yankees teammate Joba Chamberlain, whose “rules” generated considerable debate during his 2007 rookie campaign.

“Go back to the days of John Hiller and Goose Gossage,” McLain said. “Those were real relief pitchers. Those were real save guys. Those were the crème de la crème.”

Having grown up as an entertainer, McLain said the pressure of winning 30 games didn’t faze him at all.

“I had more fun with it than you can imagine. I enjoyed it. First of all, I was a piano player, an organist. So I had been entertaining in small concerts since age 11 or 12. So I enjoyed the spotlight a lot. It was just part of the program,” he said.

For an encore, McLain won his second straight Cy Young Award in 1969 by posting a 24-9 record, 2.80 ERA and 325 innings pitched. In the long run, the strain of too much work finally caught up to him.

“Had we known the damage I was doing to my arm in ’68, I’d have never won 30,” he said. “By the time I got to the middle of September, my shoulder was gone. I’d had about 18 or 19 cortisone shots already that year. We were told at that time that the cortisone shots were a healing agent. They weren’t. All they did was take away the inflammation. We were told the biggest lies back then. A number of players have sued baseball and won their lawsuits. They’ve settled a lot of lawsuits based upon cortisone, because what they were telling us and what they were preaching to us was 180 degrees from the truth.

“All it did was take away the inflammation and allowed us to believe that we were healing. The tear never healed. All we did was compound the issues, but we didn’t know it then.”

Fueled by high salaries, baseball has probably gone from one extreme to another – from overuse and misuse of prize pitchers to handling them with kid gloves. Balancing a player’s best interests with the need to win is a delicate balancing act. In McLain’s estimation, the pendulum has swung too far in one direction.

“If the name of the game is for a guy to have a long enduring career where he gets taken care of, then that’s where they’re at today,” he said.

“If the name of the game is winning then they’ve got it all backward. It ain’t what they’re doing.”

Paul Post is a contributing writer to SCD.