Profiles

Buck Barker remembered by his peers

If you read about the history of sports card collecting or talk to people who have been in the hobby for years, a few names are mentioned frequently One of those names is Charles “Buck” Barker. People who knew Barker will typically have a smile on their face when they start reminiscing. I never met Barker, but I am sure I would have enjoyed talking to him about sports and collecting. I knew SCD readers would appreciate knowing something about the man from some of those who knew him personally.

Unlike the situation with some of the early collectors, such as Jefferson Burdick, there are a fair number of people still around who knew Barker. Barker was born in 1911 and died in 1982. He was about 12 years younger than pioneer collectors Burdick and John D. Wagner, and eight years older than Lionel Carter and Bob Jasperson. He started collecting as an 11-year-old in 1922, and continued into the modern era. Depending on who you talked to, he was viewed as a thorough and dedicated researcher, baseball’s biggest fan, a defacer of cardboard or out of touch with the hobby.

Barker was always a card collector, but it took him quite awhile to find out there were other hobbyists out there. His name doesn’t appear in the vintage hobby publication Card Collector’s Bulletin until the mid-1950s, although he had been corresponding with collectors well before then. But once Barker got going, he was involved prolifically. He wrote numerous articles for Card Collector’s Bulletin and other hobby publications. He became the person to contact if you wanted to report an obscure set or variation. He searched out new issues through constant contact with a cadre of collectors throughout the country and overseas. Burdick credited Barker with being responsible for most of the baseball issues added to the 1960 American Card Catalog, which was an update of the 1953 catalog.

Barker, Carter and Wagner were known as the “Baseball Card Boys” among the early collectors. Barker was a primarily a baseball fan and all-around dedicated collector. I re-read old publications and letters from Barker and talked to several long-time collectors who shared their recollections of him and the early days of the hobby.

Background

Barker lived in St. Louis his entire life, except for a brief stay in California in the mid-1940s. He received a B.S. in chemical engineering from Washington University in 1933. He was the senior plant engineer for National Lead Co.’s Titanium Pigment Division in St. Louis.

He was a tall, quiet man with a full head of hair. He rode his bike to work for years, well before the Lycra-clad, cycling-commuters of today. He also played second base on the company softball team. He was married to Alice Barker (nee Wiethuechter, who collected dog cards), and they owned three dogs. They had a daughter, Patricia June Eberhardt, who lived in California.

He wrote notes to collectors and visited other collectors whenever possible. If he got to another city, he would check in with other hobbyists and head straight for the likely sellers of old baseball cards. He had an uncontrollable urge/obsession to pick up cards, the more obscure the better.

Bob Solon’s recollections

Another well-known hobby name, Bob Solon, met Barker for the first time in 1958 and kept in touch until shortly before Barker’s death. Solon recalled Barker as a man who found cards though collectors and sellers rather than by going to the companies issuing cards (although we’ll learn he did that, as well.)

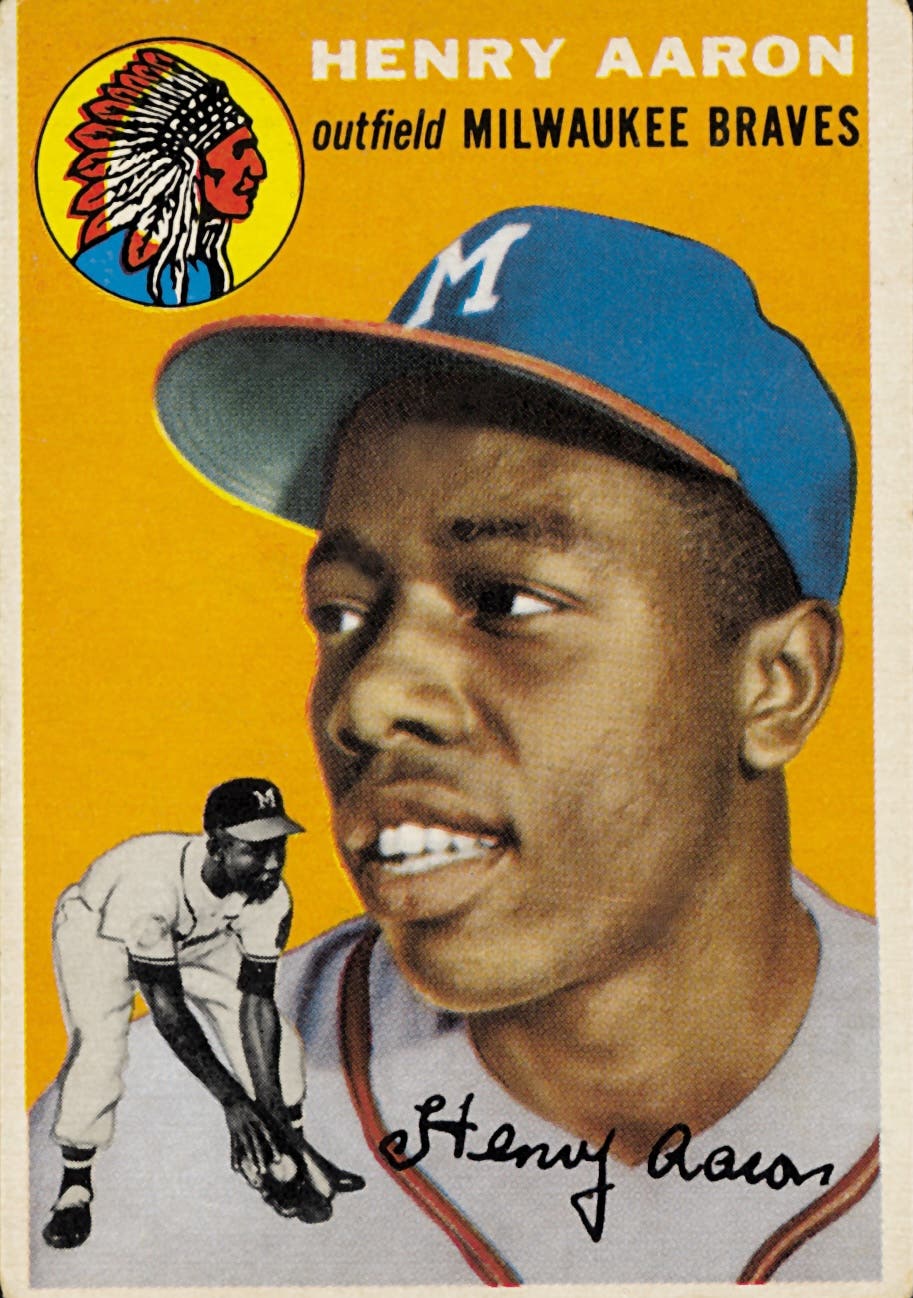

Solon commented that both he and Barker were looking for cards of every player who had ever appeared in a major league game, which they knew to be an impossible task. Barker even ventured into collecting cards of Latin American and Japanese players. For example, he was more interested in finding a card of an obscure 1955 bonus baby who sat on the bench, such as Alex George (an 18-year-old who batted 10 times for the 1955 Kansas City Athletics, getting one hit and striking out seven times) than picking up another Stan Musial card.

When a card wasn’t possible, an image would suffice. Photographers such as George Brace might even have the image, since for years Brace would photograph the players on all the teams coming through Chicago. However, the next challenge would be to sort through Brace’s stuff to find the obscure player’s photo. Barker might even contact the player directly to get some type of photo.

Barker became a champion checklister and investigator of new issues in his quest. According to Solon, Barker would track down the most obscure issues, such as Milwaukee Sausage’s Seattle minor leaguers, Henry House Sausage and Seattle Popcorn. He accumulated cards that not many others had or even knew about.

“He was very talented in pursuing historically important issues,” Solon added.

‘Youngster’ Bill Mastro

Bill Mastro was a teenager when he first contacted Barker. Mastro found him to be a prolific writer who would respond to requests for help and information.

“He was very helpful in checklisting issues and was a major contributor to the hobby’s information about baseball cards,” said Mastro.

Barker was also from an era the young Mastro didn’t quite understand.

Mastro was into collecting and wanted to get going. If he needed something, he wanted to acquire it quickly. The pace of most of the older collectors in the 1960s moved at the speed you’d expect if you sent someone a list. They researched what you needed and what they had, and then responded with trade offers to avoid anyone having to pay much for the cardboard. If you were a teenage collector, the veteran collectors all seemed like they were 100 years old, even if they were only 57, like Barker.

The pricing of cards from the American Card Catalog seemed like a good deal to the young Mastro. He phoned Barker in 1968, which was not the way collectors operated then. As my father reminded us, long-distance phone calls were reserved for major events, like emergencies. Mastro met with Barker on many occasions and visited his home to buy cards.

This was still a time when veteran collectors could conceivably complete their sets by writing to the issuers in search of high numbers or missing numbers. While Solon said that Barker didn’t do this as much as some others, apparently Barker had pretty good contacts with Topps. In 1968, Topps issued its 12-card 3-D test baseball set, an incredibly rare and expensive set today. Topps sent a few sets for a price to at least three collectors: Bill Nagy, Larry Fritsch and Barker.

Mastro was hot on the trail of this test issue in 1968. He couldn’t obtain a set directly from Topps, so he phoned each of the three people who had received 3-D sets. Nagy and Fritsch wouldn’t sell their new-found sets. Barker wasn’t really interested in selling the set either, which had just come in the mail. Mastro said that he would pay Barker $80 for the 12 cards, an unheard of amount for any set of new cards. Barker thought for a moment and decided that, if Mastro wanted the cards that much, he could have them for $80.

Writing on the cards

One of the idiosyncrasies that many people will mention is that Barker wrote on his baseball cards. Carter couldn’t imagine writing on a card. However, Mastro pointed out that at the time Barker collected cards, they really were not worth that much, nickels for the most part. Barker was delighted to find a card that he needed. To keep track of how he got the card, he would write the name of the source on the back of the card in very light pencil, along with the last two digits of the year the card was received.

“Mastro 68” meant that this was a card Barker obtained in 1968 from Mastro. Likewise, when Barker sent his cards to others, he assumed they’d like to know where the card came from (Buck Barker), sort of like personalizing a slabbed card holder today. Old cards will still turn up today with “Buck Barker” in light pencil on the reverse. When a player was traded to another team, Barker might also resort to updating the team name on the card in pencil.

Lionel Carter’s tribute

Following Barker’s death, Carter wrote a tribute that appeared in SCD in 1983. Carter had traded with Barker since the late 1940s. Barker visited Carter starting in 1954, and even stayed at Carter’s home near Chicago. Barker asked Carter for some leads for places to find cards. Carter pointed him toward a store on North Avenue in Chicago. While Carter went to work, Barker went to the recommended store and dug around all day, coming back with an incredible assortment of old cards. Carter had fellow Chicago collector Bob Wilson over, as well, and they swapped cards late into the night. Carter remembered Barker as a gentleman, not a braggart, and as someone who would sit back and listen to others, was rather thrifty and not interested in paying big bucks (like 50 of them) for a Wagner card.

In the 1983 tribute to Barker, Carter wrote, “He was what might be termed a card collector’s card collector. He was about as interested in adding to your collection as he was in adding to his own. Send him a want list, and he’d mail back a stack of cards, along with his want list and write, ‘Send me some of my wants in return when you come up with some.’ But I always seemed to have stacks of his duplicates on hand just waiting to become part of my collection if only I could find some he wanted. Often it became a rather complicated deal of swapping my duplicates to other collectors for Buck’s wants so I could swap them to him . . . It must have been in 1954 that we first met. He paid me a visit, bringing more baseball cards in his suitcase than clothes.”

In 1958, Barker, Charles Bray of Pennsylvania (then editor of The Card Collector’s Bulletin) and Preston Orem of California came to Chicago, so Carter organized a meeting at his home and included Chicago-area collectors Wilson, John Sullivan, Solon, and Bill Leonard of the Chicago Tribune.

In today’s dollars, the group probably had at least $10 million worth of cards to choose from. They had a great time swapping cards, with no money changing hands.

“It was odd that Buck and I were such good friends, as our collecting methods differed so much,” Carter noted. “I was always known as the most particular collector in the hobby. Buck liked to sort through his cards, handling them, wearing off the corners, sometimes carelessly bending them. He liked to group them by team rosters in 1922 or 1927 or 1933, mixing and interchanging the sets to get the proper players with the proper team for that certain year. He kept his cards in dresser drawers so he could get at them at a moment’s notice, the cards contesting with the socks, handkerchiefs and underwear for space.”

St. Louis Collectors’ Club

In the mid-1970s, a number of younger collectors got things rolling in the St. Louis area by having meetings or shows. Some of the people who met Barker through the St. Louis shows included long-time collectors or dealers, such as Roger Neufeldt of Oklahoma, B.A. Murray and Barry Krizan of Illinois. Each of them described the sensation that would be caused when Barker showed up at a show.

While not an official officer of the club, Barker was sort of the president emeritus. Collectors set up tables (after paying the $1 rental fee) and would be selling or trading their duplicates of Topps, Bowman, Goudey and earlier cards. Barker would show up in the middle of a show, and everyone would stop what they were doing, including the people sitting behind tables. Soon everyone who was interested in cards would gravitate toward Barker to see what he had brought. He brought cards in egg crates. He brought obscure sets and singles that were not even known to some of the collectors. It was a plethora of rare and unusual cards, and Barker was very modest in the prices he thought would be fair. The prices must have been below market in that everyone wanted to buy from him. It got to the point that when Barker arrived, he would be given a table on the stage and friends, like the late Rich Hawksley, would organize the potential buyers in a single-file line to see him.

Krizan remembered how Barker had learned the characters on the back of the rare Japanese cards that he owned.

“Buck was quiet, soft-spoken, almost shy, and he didn’t particularly like crowds,” Krizan said. “He was given great respect as the No. 1 collector in the St. Louis area.”

Krizan visited Barker at his home six times. Barker was thrilled to find other collectors like Krizan who had an interest in the cards and their history. During his visits, Krizan saw that Barker also collected baseball magazines, Latin American postcards, bullfighting programs and photographs.

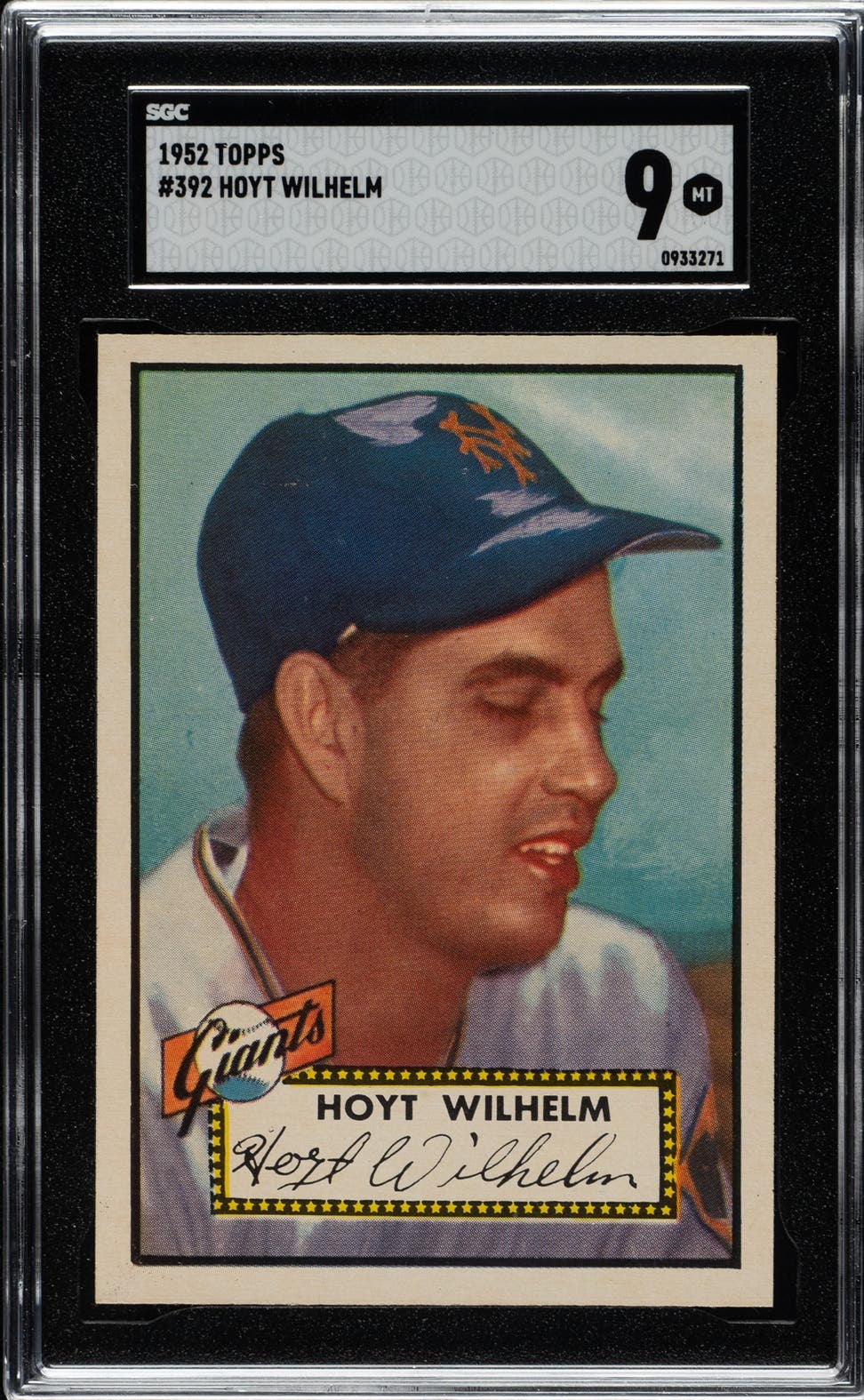

Neufeldt confirmed the sensation that Barker caused by walking into a hobby show, as collectors and dealers alike would try to rush the stage of the Holiday Inn. For example, Barker might bring to a show ’52 Topps high numbers, 1969 Topps team posters, a 1963 Topps presentation set or 1941 Goudeys, including color variations, Red Hearts and E-120s. The material was hard-to-find issues, and the quantities were significant. Neufeldt said that Barker could (and did) talk for hours about cards.

Solon remembered that Barker was adamantly opposed to the idea of premiums for star or rookie cards, and felt that the hobby was on the wrong track in charging escalating prices for stars and rookies. He felt premiums should be assigned only to scarce cards or variations. One Babe Ruth to rubber band in with the 1927 Yankees team would be enough.

Consequently, Barker’s approach of valuing every card the same was out of touch with the hobby as it evolved, although it guaranteed long lines at his table.

Carter wrote more bluntly in 1983 that when Barker began “attending conventions, he was ripped off on much of his material, as he was almost unaware of the values. What a shock to Barker, who had always insisted that the ‘other fellow’ get the best of any deal.”

Murray of Carbondale, Ill., is a fountain of information regarding the hobby in the 1970s and early 1980s. He was also a member of the St. Louis Collectors’ Club and has great memories of how collectors got to know each other by meeting and staying at hotels for weekend shows in St. Louis, Kansas City, Chicago and Indianapolis. Table fees might be $15 for the weekend and “dealers” showed up with their shoe boxes. In addition to Barker, attendees would include Hawksley, Wirt Gammon, Gar Miller, Pat Quinn, Don Steinbach, Bill Hickerson, Fred Ronniger, Fritsch, Jim Zak, Ross Beatle, and many others still active in the hobby.

Hall of Fame Collector Buck Barker

In 1971, Irv Lerner, with the help of Bob Jaspersen and Richard Reuss, published a supplement to their Who’s Who in Card Collecting. Included was information on new Hall of Fame members Barker, Wagner and Carter.

The information on Barker (written by Carter) contained the following:

“Recognized as the top authority on card issues, Buck Barker is pushing closely on the heels of Jefferson Burdick for the honor of having done the most for the hobby of card collecting . . . He undertook the listing of new issues, was associate editor of the last issue of the American Card Catalog and much of the present system of listing sports cards was due to his effort. His many articles to almost all our hobby magazines are always informative, interesting and inbred with that special Barker sense of humor that is so much a part of the man. Collectors who turn to him for assistance in preparing checklists or checking want-lists are never refused, regardless of the time and effort required.

“Barker began collecting in 1922, and it is not surprising that the first set he collected, the E120 American Caramel baseball set, remains one his favorite sets. He also points with pride to his 400 different No. 172 Goodwin Baseball cards and 165 different E145 Cracker Jacks . . . One of the big thrills of being a card collector is to be visited by Buck Barker. The ready wit, the quick smile of the man are infectious. He’ll talk baseball and cards to you all night.”

Barker’s writings

Following the logic in some of Barker’s writings can be a challenge. You might call his approach a “stream of consciousness,” in that he could switch from one topic to the next within the same paragraph. Once you had an idea of what he was writing about, it all made sense, although it could be exhausting.

For example, in a 1968 letter to Carter, Barker writes. “I owe you 50 cents for Louden – so (If you need him) I’m sending Hugh Ferris to pay – but since he’s worth more than that, you owe me something to balance. Going to Mexico next year. Would have gone this year but for the Olympics crowding. Looks like you are right on the Tigers this year. Ever get any Pro Pizza? Adios, Buck, El Toro.”

In 1955, Barker wrote a long article for the Card Collector’s Bulletin on how the Fine Pen and Wide Pen Premiums were distributed. In 1956, he and Dick Dobbins collaborated on an article about Pacific Coast League cards. In 1957, he discussed new issues and variations, including the 1955 Bowmans. In that article, we get a little insight as to his early collecting.

“I remember how all the kids were collecting baseball ‘flips.’ Naturally, in the year 1922 in St. Louis, the popular cards (in E120 and E121) were the Brownie stars, who just missed the pennant that season.”

In the 1970s, Barker wrote a letter to Carter that he was still looking for E cards, T207s and M116s, but he had decided not to exert himself on cards now “except to obtain: 1) one card of each player; 2) one card of each set; 3) favorite sets; 4) Latin American players; 5) favorite players (Minoso and Ashburn); and 6) anything else that really strikes my fancy.”

You can see he was cutting way back in his interests.

Barker kept up his frequent contributions to hobby publications and the American Card Catalog, writing about early tobacco issues, postcards, English tobacco cards, Topps issues, regionals, contacting issuers, tributes to Jefferson Burdick, auction results and correspondence with collectors.

One particular article from 1960 hit pretty close to home. Barker observed that there was greater activity and satisfaction in the early stages of collecting when great progress was made in completing sets, and practically every opportunity to purchase cards was fruitful. But as a collector progresses “the rarities usually come at higher prices. In order to obtain a few cards every month, he must write many fruitless letters and keep hot on the chase, but the disappointments will be many. Often there is no use writing old friends, as none will have anything for trade. Then he’s reduced to writing articles, a sad state indeed.”

End of the collecting line

In his last few years, Barker started selling off his collection. Collectors and dealers were happy to pay whatever he asked for the rare cards. In November 1982, he went in the hospital for gall bladder surgery. Buck’s wife Alice wrote, “One day he is doing fine, and the next morning at 4:30 a.m., they called and said he died . . . We all loved Buck so much. He was good to everyone and everything.”

Following Barker’s death, his widow worked with Hawksley of St. Louis, and the collection wound up with Hawksley, Lew Lipset, Tommy Reid and a small portion with Mastro, based on Mastro’s recollection of the events. It had been one of the most extensive collections of baseball cards ever assembled.

Barker was a baseball fan. He had not collected stamps or coins and had never been too concerned about condition. He just liked the cardboard.

If you see a card with “Buck Barker” written on the back, keep in mind the rest of the story.

_____________________________________________

George Vrechek is a frequent contributor to Sports Collectors Digest. He can be reached at vrechek@ameritech.net.