Memorabilia

Still Striking the Pose: Visiting With the Oldest Heisman Winners

By George Vrechek

There are approximately 1.1 million students playing high school football in the U.S. It is estimated that 67,000 play football at all college levels. There are 120 Football Bowl Subdivision schools offering 85 scholarships each to 10,200 players. Each year one college player receives the Heisman Trophy. Of the Heisman Trophy winners prior to 1955, two of them are still alive. I was fortunate to talk to both of them about their careers, cards and memorabilia.

JOHNNY LUJACK, HEISMAN ’47

Johnny Lujack was on the cover of national magazines, signed a lucrative pro contract and was featured on numerous cards despite playing before the boom days of card collecting and only played professionally for four years. Lujack (age 89) played for Notre Dame in 1943, served in the Navy in 1944 and 1945 (V-12 Program) and returned to Notre Dame for 1946 and 1947. He was drafted No. 4 overall in the 1946 NFL draft and played for the Chicago Bears from 1948-51. He was athletic, smart and handsome.

At Connellsville High School, south of Pittsburgh, Lujack lettered in three sports, was elected class president and graduated as the valedictorian. Lujack’s Notre Dame teams coached by Frank Leahy went 26-1-1 and won three national AP titles the three years he played varsity football. In 1947, Notre Dame was 9-0, and Lujack passed for 777 yards and ran for 139 yards. (In 2012, Heisman winner Johnny Manziel passed for 3,706 yards and ran for 1,410 yards.) In the Heisman voting, Lujack had 742 votes, Bob Chappius 555, Doak Walker 196, and Charley Conerly 186. Lujack was named the Associated Press Athlete of the Year for 1947.

Professional career

In the pros, he played quarterback and defensive back and kicked extra points. He had to compete at quarterback against Sid Luckman and Bobby Layne. He threw for six TDs and set an NFL record with 468 yards passing in a victory over the Chicago Cardinals in 1949. After four years in the pros and injuries to his shoulders, he quit and became an assistant coach at Notre Dame for two years. He went into broadcasting, and in 1954, purchased an auto dealership in Bettendorf, Iowa, where he and his wife still reside. Lujack has been a generous contributor to Notre Dame, Connellsville High School and many charities.

Appeared on many cards

Lujack played on one of the most prominent undefeated Notre Dame teams; he was a war veteran and successful in the pros. It was natural for companies to want to feature him on cards, photos, articles and ads. His vintage football cards include Exhibit Supply Co., 1948 Topps Magic, 1948 Wilson Advisory Premium, 1948 Bowman, 1949 Leaf, 1950 Bowman, 1951 Bowman, 1951 Wheaties and 1955 Topps. Impressively, in 1948 as an unproven rookie, he was featured in sets with very few other players: Topps Magic (13 players), Exhibit Supply Co (60 players) and 1948 Bowman (108 players). He has also appeared on various recent card issues. He was on the cover of Life, Look, and Sport magazines. I found 520 eBay listings for cards, photos and memorabilia featuring Lujack.

I talked to Lujack after he returned from the golf course in Indian Wells, Calif. He told me he loves to play golf but has had some neck problems this year. The shoulders that bothered him in the pros have not been a problem. He says he still gets 5-10 cards or photos each week to sign. If people provide a SASE and are not asking for anything unreasonable, he signs and returns the items and is amazed at where it all comes from. He said he “wasn’t that sure what cards they send.” He wasn’t that familiar with the vintage cards.

Comments from Lujack

Lujack jokingly told me that what he liked most about being the oldest living Heisman winner was the “living” part. He sees a few of the shrinking list of fellow old-timers at least annually, including Fred “Curly” Morrison (87) and Ed Sprinkle (90). Although Lujack played against Charley Trippi (92) several times, he said he hadn’t really met Trippi.

Lujack had many interesting stories, recalling, “As a sophomore in the spring of 1943, I was in the Navy. There was no spring football, so I played baseball. I had started on the basketball team earlier. In the first baseball game, I had two singles and a triple. Between innings I went over to the track meet and won the high jump and javelin and got letters in four sports that year, the last one to do so at Notre Dame.”

“In 1948, my first time in Green Bay, the fans stoned our bus. Green Bay had an end that I had to guard who ran a down out and up. I picked off the pass. I got three that day; he got none.” (Lujack had eight interceptions that year.)

I had read that he had shoulder problems in the pros. Lujack told me that he had a complete separation of his left shoulder and a partial tear in his right (passing) shoulder in 1951. That final season he said, “The guys would block and I ran more.”

Lujack remembered, “The Notre Dame or Chicago Bears publicity people told me to pose for pictures at practice, and I did whatever they asked.” He didn’t recall having any direct contact with Topps or Bowman or them paying him much of anything. He didn’t have an agent and dealt with companies like Wheaties directly. He thought that they may have paid him $25 or $50, but whatever it was, it wasn’t much.

“My salary the four years with the Bears was $17,000, $18,500, $20,000 and $20,000, and they weren’t drawing that many fans then.”

In today’s dollars, $20,000 would be $188,000. Lujack getting that kind of money out of George Halas might have been his greatest accomplishment.

JOHNNY LATTNER, HEISMAN ’53

Like Lujack, Johnny Lattner (81) was a talented multi-sport athlete. He played at Fenwick High School in Oak Park, Ill., for legendary Chicago Catholic League coach Tony Lawless.

Lattner also played on some great Frank Leahy Notre Dame teams that were 23-4-2 during his three-year career. Johnny Lujack coached quarterbacks at Notre Dame while Lattner was there in 1952 and 1953. Like Lujack, Lattner played offense, defense and kicked. In his senior year, the team was 9-0-1 and was ranked first or second nationally, depending on which poll you liked.

Close Heisman vote

Lattner won the Maxwell Award as the top collegiate player in 1952 and 1953. He won the 1953 Heisman in one of the closest votes ever with 1,850 votes over Paul Giel with 1,794 votes. (Giel received a $60,000 bonus to play pro baseball rather than football and pitched in the majors from 1954-61.) Lattner said that he was still playing both offense and defense in 1953, which got publicity. Lattner recalled playing 54 minutes of the Oklahoma game.

I asked Lattner about a memorable photo of him making a great over-the-head catch of a long pass. “That was against Navy in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. Leahy told us you had to look the ball in. I did that and it looked easy. “

It probably didn’t hurt Lattner that Notre Dame games were televised nationally – sort of. Films of each Notre Dame game were edited down to 30 minutes and shown on Sunday mornings. Fans knew the names of the backs: Guglielmi, Worden, Heap and Lattner, all of whom played in the pros. They have become known as the “Forgotten Four,” which puzzles me because as a young TV watcher, I certainly never forgot them. Lattner never forgot the others either, staying in touch frequently after college.

All-Pro as a rookie

In 1954, Lattner was drafted No. 6 overall in the first round by the Pittsburgh Steelers. He was paid $10,000 for the season, plus a $3,500 bonus at a time when the typical player was making $4,000. Lattner was big, speedy and elusive. Lattner felt that playing in the pros was just a stepping stone to “making a name for yourself and getting into business.”

Bowman used a picture of Lattner that he recalls being taken his freshman year at Notre Dame showing his No. 14. Someone with the Steelers already had No. 14 so he got No. 41 as a pro. Lattner didn’t recall how much money he got from Bowman, if any, but did remember getting a big package of gum from them. He also remembered seeing the card when he was in his first training camp. He appeared on the last card in the 1954 Bowman set.

In his rookie season, he recalled trying to block Len Ford (Cleveland Brown HOFer) and having trouble. He added, “We didn’t use facemasks in those days and I remember trying to block Geno Marchetti and winding up with my face in the mud.” However, he gained 237 yards rushing, 305 yards on 25 pass receptions, scored seven touchdowns and returned punts and kickoffs for 486 yards. He made the Pro Bowl as a rookie. He made a name for himself.

Playing with the Air Force

With the Korean War (1950-53) going on while he was in college, Lattner was advised to join the ROTC, otherwise he might be drafted out of college. He joined the Air Force ROTC, which required him to serve two years of active duty after graduation. Heisman runner-up Paul Giel also wound up serving two years in the Army. Lattner went on active duty in 1955.

It wasn’t unusual for the military services to put their professional athletes to work – playing. Lattner was assigned to Bolling Air Force base near Washington, D.C. One of his principal duties involved playing on the base football team with several other pros, including Notre Dame teammates Dan Shannon, Joe Heap and Ralph Guglielmi.

“They had us scrimmage the Redskins on several occasions and we nearly beat them, except I hurt my knee playing in those games,” Lattner stated. He tore his ACL and had cartilage damage as well. Surgery took care of the cartilage, but the ACL couldn’t be repaired at the time.

“I couldn’t cut with speed. I tried wearing a rubber inner tube around the knee, but if I ran a mile or two, the knee would swell up. When I got back to the Steelers in 1957, I knew I was through.”

Lattner coached for a few years and then opened a restaurant in Chicago, which he ran until 1973. He has usually led off Chicago’s huge St. Patrick’s Day parade at the front of the Shannon Rovers Pipe Band. The band used to adjourn to Lattner’s restaurants for refreshments after the parade. He was a long-time participant in the Old Timers spring football games at Notre Dame. Lattner is outgoing, friendly, optimistic and enjoys life.

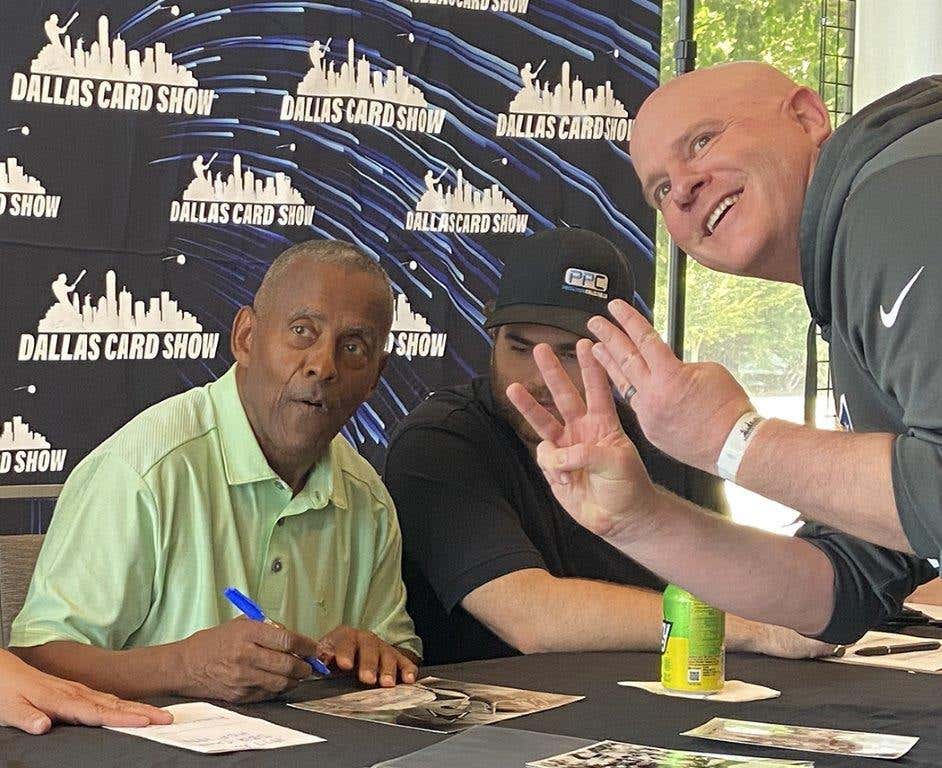

Despite having only one vintage football card, there were 555 listings for Lattner items on eBay when I checked. Lattner appears on many recent cards produced by Fleer, Upper Deck or Notre Dame University. He was also on the cover of Time and Sport magazines. Lattner has signed at sports collectors shows in Chicago and will sign and return items sent to him, if a SASE is included. He gets a few letters each day.

After football

Following the restaurants, Lattner worked in sales in the printing business and remains a vice president with PAL Graphics Inc. near Chicago. He remains in the Oak Park area, has eight children and 25 grandchildren. Lattner offspring have continued to play sports at Fenwick High School. Last year there were four Lattners on the football team. His Heisman Trophy has wound up being loaned to various charities to raise money.

The Heisman boys seem to stay in touch, since when I talked to Lattner he had just returned from a gathering with Roger Staubach in Dallas. There were five Heisman winners from Notre Dame in 11 years: Bertelli ’43, Lujack ’47, Hart ’49, Lattner ’53 and Hornung ’56.

Dick Kazmaier, Heisman ’51

When I began research for this article, Dick Kazmaier, winner of the 1951 Heisman, was still alive. Kazmaier died at age 82 on Aug. 1, 2013, from heart and lung diseases. Because of his declining health, I was never able to talk to Kazmaier; however, I did send him my draft of his biography, which he read. I received comments back through his firm and include his story as well in this article to recognize his significant achievements.

Dick Kazmaier’s lone vintage football card (1955 Topps No. 23) shows him in his Princeton jersey with the distinctive striped sleeves. Since Kazmaier never played in the NFL, it was fair game for Topps to use his image in 1955 when Bowman issued NFL cards. His 1955 Topps card is referred to as his “rookie” card; however, he was never a rookie. He was the youngest player in the Topps set. (Lujack was out of the NFL in 1955, so he also made the Topps set. Lattner was still under contract with the Steelers and Bowman and couldn’t be included in the Topps set.)

I thought Kazmaier looked pretty neat in that uniform and pose, and I taped his card to the bulletin board in my bedroom in 1955. I still have the card, but the tape on the back makes it hard to read his story. He also appears in a 1992 Heisman set.

Kazmaier followed in the footsteps of initial Heisman recipient Jay Berwanger in deciding not to play professional football. Instead, he opted for Harvard Business School and “real” work. His story is one of determination, success and planning.

Fifth string at Princeton

Kazmaier was a five-sport athlete from Maumee, Ohio. Although only 5’11” and 155 pounds, he caught the attention of two Princeton alums and was accepted at Princeton. When he arrived as a freshman, he felt overwhelmed trying out against 120 other players who were either high school team captains or most valuable players. Princeton was a powerhouse in the early years of college football starting in 1869, and was still competitive into the 1950s. Kazmaier found himself on the fifth-string freshmen team. He got into some games, but varsity coach Charlie Caldwell viewed him as “too small for varsity athletics.” Caldwell didn’t know Kazmaier very well. He was a “terrier for detail” and a hard worker.

Kazmaier went out for the freshmen basketball team and wound up as their leading scorer. He developed confidence, added 15 pounds to his frame and arrived at the varsity spring practice in 1949 with a determination to succeed. Offenses in those years had some similarities to today’s spread offenses, with the tailback receiving the snap in the single wing backfield and having the option to either run or pass. They ran much more frequently in those days, but Kazmaier seemed to be able to set up the defenses so that his passing was effective, as well as his elusive running. He became the starting tailback as a sophomore and led the Ivy League in total offense.

Beating Cornell and winning the Heisman

In 1950, Kazmaier’s junior year, Princeton went undefeated and was ranked No. 1 in the nation in some polls. Their big rival was Cornell. The 1951 Cornell/Princeton game confirmed Kazmaier’s Heisman candidacy. Both teams were undefeated going into the late October showdown. Kazmaier was the only returning starter from the prior year’s undefeated Princeton team and it was expected to be a close contest. Kazmaier completed 15-of-17 passes and ran for 124 yards and two touchdowns to clobber Cornell 53-15.

In 1951, Kazmaier led the nation in total offense with 966 yards passing and 861 yards rushing. Princeton went 9-0 for the second consecutive year and ranked No. 6 in the National AP Poll. Kazmaier received 1,777 votes for the Heisman; the next closest player received 424 votes. He made the cover of Time. Kazmaier accepted the award and returned to classes. He said there was no commercial benefit or income involved.

Life after football

Kazmaier said that he didn’t think professional football was the path for him after college. He didn’t want to be diverted from his goal of going to business school and getting a good job. He mentioned the need “to seize the day” and continue his education. He played in the East-West Shrine game, was drafted by the Chicago Bears (176th overall pick), but decided to attend Harvard Business School instead.

Following Harvard and a few years in the Navy, he worked his way up to head of the sports divisions of several major corporations. In 1975, he started his own company, Kazmaier Associates Inc. The firm has provided sports advisory services and owned, licensed or distributed major sporting good brands. He served as the company’s chairman and on various boards including Princeton’s. Three of his six daughters are Princeton grads.

The composite fantasy vintage Heisman winner

If you could put the energetic Heisman winners mentioned together, you’d have a friendly valedictorian who went to Harvard Business School, lettered in five sports, served in the military, ran/passed/kicked their team to a National Championship, played both ways, never got to wear a face mask, was generous to their schools, gladly signs autographs, was successful in business, enjoys playing golf and never made more than $20,000 in a year playing football. As a bonus, you can still buy their card for a reasonable price.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to SCD and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.