Memorabilia

Stadia Collector: Revisiting Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City

By Paul Ferrante

It’s funny how history is sometimes all around us and we don’t even notice. Let me give you a couple of Stadia-related examples.

First, back in 1975, my Iona College football team went down to the beautiful Bronx to play Manhattan College on a sun-splashed September Saturday afternoon. The venue for this small college gridiron tilt was Gaelic Park, a public facility hard by the EL tracks (Manhattan did not have its own stadium).

The very strangely cool thing was that to enter Gaelic Park, which was the scene of countless athletic events and music concerts, one had to pass through the Irish bar at its front. I kid you not. Imagine a college football team, fully suited up, walking single file through an Irish pub (with a few bemused old-timers sipping Guinness at the bar) and out the back door to the playing field!

Anyway, what I didn’t notice that day as we hammered the Jaspers were the two rows of stadium seats that ran the length of the visitors sideline, set back about 10 yards. Why were they even there? Nobody knew or cared. The thing is, I would learn in the late 1980s when I started researching ballparks that these seats were original straight-backs from Ebbets Field that had been removed and transferred upon its demolition.

Of course, I scurried down there, only to find that they had been secured, in peeling and rusting piles, in a corner of the fenced-in property, exposed to the elements, where the owner – who despite my cajoling would not sell me even a single one – was readying to relocate them to a storage facility where he could cash in on his now sought after sports relics. Whatever became of the Gaelic Park stash, I have no clue. Maybe they’re still sitting in some warehouse.

And then there was my trip to Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, N.J., on Aug. 23, 1974. It was my best friend Matty’s birthday, and I could think of no better gift than to purchase tickets for us to a rock concert – our first – featuring one of our favorites, the Beach Boys . . . with the Eagles serving as the opening act! As we had just graduated high school, transportation to this far-flung outpost would be a problem for these two car-less lads. So, we took the train from Westchester to Grand Central Station, and then rode the subway out to Jersey City. This whole experience was both new and exotic, and it took hours. But finally we arrived, all revved up, at our destination.

By 1974, Roosevelt Stadium was starting to deteriorate. I remember remarking to Matty, “What a dump!” as we opted to use our general admission tickets to lay down a blanket on the patchy outfield grass not 25 yards from the stage. It was hot and humid as the gates opened in the late afternoon for the evening concert, and the variety of liquid and herbal libations flying around us was astounding. I don’t know how many thousands of kids were there; all I recall was that the Beach Boys sounded great as always, and the relatively new band called the Eagles was pleasant – especially with a number called “Witchy Woman” that would provide the inspiration for a T.J. Jackson novel I would write in 2014.

I never made it up into the stands to check out the seats, or any other fixtures, as the Stadia Collector in me would not be born for another decade or so. Which is a shame, because by that time Roosevelt Stadium, like so many other classic parks from the first part of the 20th century, would be wiped off the map. But its story is an interesting one, providing a unique challenge for collectors, as we shall see.

The early days

The site of Roosevelt Stadium, at Droyer’s Point on Newark Bay in Jersey City, had formerly been that of Jersey City Airport. Then in June 1929, the announcement was made by Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague that a multi-purpose facility would be constructed, with the ability to hold 50,000. It eventually came under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression and was named after then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The style employed in the outer façade was Art Deco. Total cost of the project ended up in the area of $1.5 million.

The park was single-decked, and covered from home plate out to the corner bases. Then, uncovered pavilions stretched to the outfield. Center field was open beyond the fences and dominated by a huge scoreboard clock reminiscent of Shibe Park’s. In a way, the entire symmetrical design was similar to Cleveland Stadium, though on a smaller scale. The dimensions for baseball were 330 feet to left, 411 feet to center and 330 feet to right. The actual grandstand seating came to 24,000.

The idea was that Roosevelt Stadium would serve as home field for Jersey City’s triple-A International League affiliate of the New York Giants. This it would be from 1937-50. Other minor league baseball clubs would play there as well: the Jersey City Jerseys (IL) in 1960-61, the AA Jersey City Indians (Eastern League) in 1977 and the Jersey City A’s (EL) in 1978.

The glory days

Minor league-wise, one of the highlights had to be the professional debut of Jackie Robinson in the Jersey City Giants’ season opener against Robinson’s Montréal Royals on April 18, 1946. Robinson was four-for-five with a three-run homer, scoring four runs and driving in three. He also stole two bases. This historic footnote sets the scene for Roosevelt Stadium’s most interesting sports legacy.

By the 1950s, Major League Baseball was undergoing significant changes. The Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee in 1953, followed by the St. Louis Browns to Baltimore in ’54 and the Philadelphia Athletics to Kansas City in ‘55. The cause of all these moves, it seems, was the inability of the home city to support multiple franchises.

Walter O’Malley, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers – one of three ballclubs in New York – saw these changes and how they benefited the relocated teams, especially the Braves, who would win the National League pennant in ’57 and ’58, with one World Championship.

O’Malley’s Robinson-led team, an integral part of the borough of Brooklyn, had finally brought home a World Series championship with a victory over the hated Yankees in 1955. The legendary “Boys of Summer” were riding high. But O’Malley, ever the bottom-line guy, looked beneath the surface to find a degenerating, antiquated ballpark with virtually no parking access in a postwar society that was moving to the suburbs and considered the automobile its chief means of transportation. Also, Ebbets Field held only 32,000, and its intimate charm worked against it as a business enterprise, despite the Dodgers drawing more than 1 million fans annually during the Robinson era.

O’Malley became convinced his only solution was a new ballpark with more seating, more amenities and ample parking. But he hit several roadblocks and butted heads with the powerful Robert Moses, chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, on numerous area sites for the relocation. Eventually, O’Malley’s plight got the attention of the mayor of Los Angeles, who offered his town as a new home for “Dem Bums.” Meanwhile, the Dodgers owner, who sought what some would term a “sweetheart deal,” saw his ideas for various sites – including a domed facility in Brooklyn – turned down.

Thus, perhaps as a shot over the bow, O’Malley announced that in 1956 and 1957 the Dodgers play seven home games in Roosevelt Stadium in New Jersey. Brooklyn fans were irate, but what could they do?

The selection of Roosevelt Stadium was based upon its relatively comparable seating capacity (O’Malley believed he could sell out every game) and its track record, prior to 1951, for supporting minor league baseball (by 1956, the Giants had left and the ballpark was being used mainly for high school football games and stock car races).

The agreement struck between the Dodgers and Jersey City was that the ballclub would rent Roosevelt Stadium for an annual fee of $10,000 and would pay for improvements that would make the park major league caliber. They would receive all parking revenue. O’Malley also took this opportunity to inform the public that the Dodgers would not play in Ebbets Field in 1958, and that he was willing to move the entire operation to Jersey City instead, which must have made the Jersey City politicos ecstatic. Initially, O’Malley envisioned tickets being sold to patrons as a package each season, but he would later make them available on a game-to-game basis.

And so, on April 19, 1956, the Dodgers defeated the Phillies 5-4 with a chilled crowd of 12,214 on hand. O’Malley, who had been hoping for sellouts, was not happy, though attendance did increase over the next six dates with better weather and promotion. The Dodgers players themselves, particularly Robinson – who was razzed by the Jersey City fans still loyal to their former parent club, the Giants – weren’t thrilled about the ballpark. The fences were farther away than in the cozy confines of Ebbets Field, and their diehard Brooklyn fans were in short supply (they did go 6-1 that first season, however). As an aside, the Giants’ Willie Mays hit the only fair ball ever out of the park in New York’s 1-0 victory on August 15.

Although the average attendance that year (21,200) outdid Ebbets Field by around 5,500 per date, O’Malley was somewhat disappointed and began downplaying Jersey City as a permanent relocation site.

By 1957, the handwriting was on the wall to all but the most steadfast of Brooklyn fans: the Dodgers were leaving. They had sold Ebbets Field to the city of New York, and rumors were flying about a move west. The Dodgers went 5-3 at Roosevelt Stadium, with the players for the most part (Robinson had retired) resigned to their fate. The team averaged 5,000 fewer fans per game in Jersey City, though this still surpassed the 1957 season average at Ebbets Field. As the club fell further out of the pennant race that summer, it became less likely that Jersey City would be the franchise’s future home. The final game at Roosevelt Stadium, a 3-2 loss to the Phillies, drew only 10,900 fans.

The other shoe dropped on Oct. 7, 1957, when Walter O’Malley announced that a deal had been struck with the city of Los Angeles to move the Dodgers to the West Coast (their closest NL rival, the Giants, would move with them, to San Francisco), thus ending the prospect of Major League Baseball in Jersey City.

In retrospect, the Jersey City venture was a gamble on O’Malley’s part to put pressure on New York City officials, but the lukewarm response of the local fan base, and the relative difficulty at that time of patrons to get to the ballpark without an arduous trip via mass transit, made it unfeasible. Did O’Malley just use Jersey City to get what he wanted? Perhaps. What’s absolutely certain, however, is that the demise of the facility began here.

Besides baseball and the aforementioned high school sports, Roosevelt Stadium hosted professional boxing, soccer and auto racing. Each summer from 1949-80 the stadium featured one of the most prestigious drum and bugle corps championships, The National Dream. During this time, more than 100 of the country’s most prominent drum and bugle corps competed for the coveted title.

The decline and end

Which brings us back to how I ended up there in August 1974. Besides the sporadic minor league baseball usage, Jersey City officials envisioned Roosevelt Stadium as a viable music concert destination. The decade of the 1970s saw a parade of top-flight musical rock groups roll through, including the previously mentioned Beach Boys and Eagles, the Allman Brothers Band; Eric Clapton; the Band; Pink Floyd; Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young; Emerson, Lake and Palmer; Alice Cooper; Lynyrd Skynyrd; Rod Stewart; Kiss; and the J. Geils Band, as well as James Brown and Tony Bennett.

But by the 1980s, the place was done; a light tower crashing down in 1979 made it downright dangerous as well. In 1982, the city council voted to tear it down and replace it with a $200 million housing development. Though many in the area had felt strongly about keeping the park, it was operating at an ever-increasing deficit. When the estimate for repairs and refurbishment came in at about $4 million, the die was cast. The city council, pointing to Jersey City’s drop in population due to what they claimed was a housing need, regarded the 90-acre plot along Newark Bay as a step in the revitalization of that area. Roosevelt Stadium, after lying vacant for a couple more years, was finally demolished in 1985, to be replaced with a gated community named Droyer’s Point in 1987.

Roosevelt artifacts at a premium

Apparently, the stadium was razed and bulldozed with little fanfare or interest in its contents, which, of course, would later make them intriguing to Stadia collectors, who hearkened back to the heyday of the 1930s-50s for the demolished ballpark.

Particularly desirable were the two variations of figural ends which graced the box seats of the grandstand. One sported the state seal of New Jersey; the other design featured an interlocking capital “RS.”

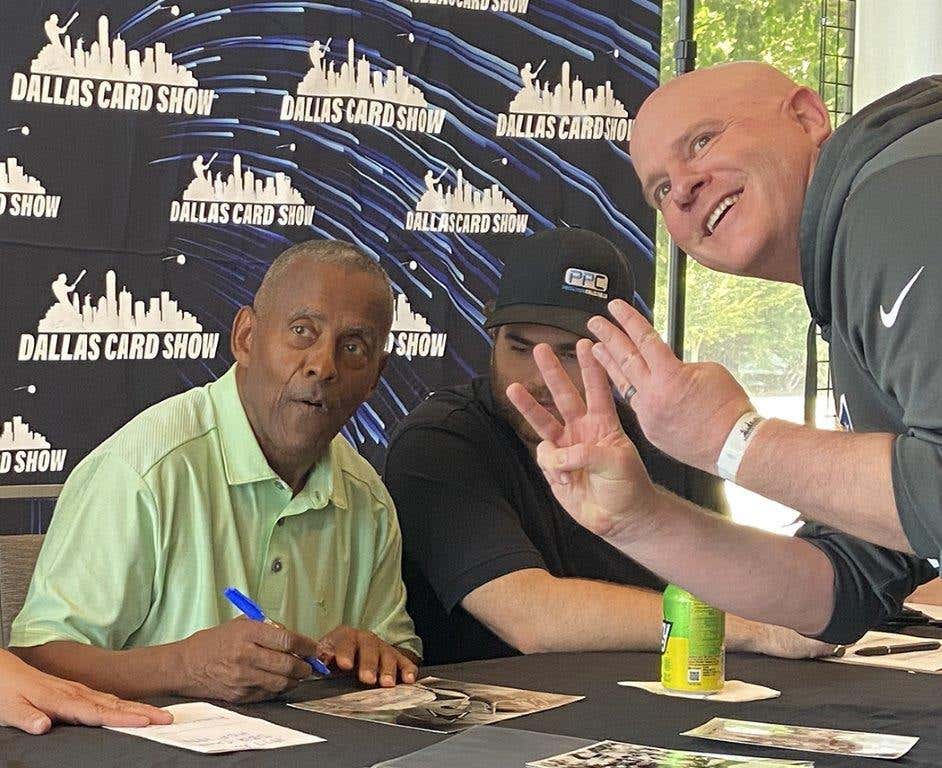

Enter our old friend Richie Aurigemma, whose website www.CollectibleStadiumSeats.com has become familiar to like-minded Stadia enthusiasts. Richie is a true Stadia hunter, running down leads from near and far in his never-ending search for ballpark relics. In this column alone, I have documented his memorable finds of Polo Grounds figurals at an amphitheater in St. Augustine, Fla., and original wooden seats from old Yankee Stadium and Shibe Park in a minor league facility in North Carolina, as well as his collaboration on a barn find of figural end League Park seats in Vermont.

Besides operating his business, he has amassed an impressive personal collection of seats and other ballpark memorabilia that would make the folks in Cooperstown envious. But the sleuth in Richie never sleeps; he is constantly surfing the Internet for rare acquisitions, and in late November 2014, his diligence paid off regarding a previously empty hole in his collection: Roosevelt Stadium.

“I was checking out an online auction site, and clicked on an item for a closer look,” Richie said. “An accompanying list came up that ran for several pages, with a photo for each piece. These items were from a large estate sale in New Jersey, apparently. One in particular caught my eye – it looked like an oversized police officer’s badge. I clicked on it to enlarge the image and it hit me: It looked a lot like the figural end design from a Roosevelt Stadium seat, which I’d seen in vintage photos.

“Sure enough, after double-checking I had made a match. Someone had apparently cut out figural ‘New Jersey Seal’ insignia from the seat stanchion, stripped it clean and had probably used it as a paperweight. What shocked me was that the ad, in neither the headline nor the description of the piece, made reference to Roosevelt Stadium. So, the chances of me finding this particular item were beyond incredible . . . I guess it was just fate.”

With his newly discovered “Jersey Seal” figural in hand, Richie figured he finally had Roosevelt Stadium checked off in his personal collection. His hope was that someday he would track down an original non-figural seat from the park and reunite the figural insert with the plain side stanchion. With any mention of Roosevelt Stadium memorabilia scarce on the secondary market (not counting vintage photographs or postcards, which can be found on auction sites), he knew this was a long shot at best.

Incredibly, though, a second find would emerge just weeks after this one.

Again, Richie was surfing the Internet classifieds late one evening when he came upon an ad posted by a gentleman in New Jersey offering, as he put it, “two connected double seats of ‘old school’ chairs.” A couple of photos were provided in the ad, showing the seats lying on the ground and photographed from straight on. They were painted in a cheerful blue, but flaking of the topcoat revealed a bright red hue underneath.

There appeared to be some kind of end figurals, but as the view in the photos was from the front, it was hard to determine. Richie did a color comparison with old photos and that matched. But he was still unsure. So, he shot the seller a brief e-mail (the seats had been listed for a week already) asking if the seats were still for sale. He also called an attached phone number. Receiving no response, he regretfully trudged off to bed, figuring he’d missed out. But the next morning brought the sweet sound of a ringing phone. It was the seller. Yes, the seats were still for sale. Richie hastily made an appointment to view the items and jumped in his car for the trip over the Tappan Zee Bridge to New Jersey.

As he neared his destination, questions abounded, the most important of which being whether the seats could really be from Roosevelt Stadium. The seller had made no mention of this possibility. Was this just a wild goose chase? But as he pulled into the driveway, Richie’s doggedness and research paid off as he spied two sets of seats, each with two ornate interlocking “RS” logos. Jackpot!

Richie now had examples of both figural Roosevelt Stadium pieces in his collection. He happily paid the man his asking price and was on his way, his treasures resting comfortably in the back of his truck. The whole deal had taken just a few minutes.

Once he got home, Richie the businessman took over. After photographing the seats and setting aside a figural for his own collection, he contacted a close friend and seat collector who had shared Richie’s quest for the elusive Roosevelt Stadium relics. The collector had, indeed, found a lone “RS” stanchion a few years previously, but needed other parts to fashion a full seat. So, Richie sold him a “half” seat with a side logo; thus, when his friend attaches his own “RS” logo stanchion, he’ll have a true rarity – a double figural single seat. But wheeler-dealer Richie wasn’t done. His next e-mail was to another good friend who owns a sports museum in the Midwest, eventually striking a deal for a figural single seat. This left him with a full figural seat for his own collection, and a half-seat needing a side stanchion to make it whole. And so, the hunt continues.

Of course, Richie would entertain offers from any collectors out there who might have the missing part – either to purchase theirs, or sell them the half seat to complete it for their own collection. Again, you can visit his website for information.

Final thoughts

Thus ends our discussion of Roosevelt Stadium. For me, it provided the nostalgic memory of a warm evening filled with music and fun with my best friend in the full flower of our youth. But it also led to a historical appreciation of a lost ballpark that is today but an afterthought in baseball lore. Until next time, please stay seated!

Collectors can e-mail Paul Ferrante at baseballjourney@optimum.net. Also, visit Paul’s website, www.paulferranteauthor.com, for updates on all his writings.