Ted Williams

Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory

By Ross Forman

Major League Baseball, as we know it today, was changed forever during a game back in 1884, when a 17 year old skipped work to attend a Louisville Eclipse game in the old American Association.

Pete Browning, the Eclipse star, broke his bat that day. John A. “Bud” Hillerich, 17, approached him after the game to invite him to his dad’s woodworking shop – because the young Hillerich thought they could make a better bat for Browning.

Hillerich spent hours turning a bat to Browning’s exact specifications. The next game, Browning went three-for-three at the plate.

Word quickly spread about Browning’s bat, and what the young Hillerich did – and could do for others. Teammates soon started asking for their own custom-made bats. Other pros did, too.

Ironically, Bud’s dad, J.F. Hillerich, wanted nothing to do with baseball; he thought the future of his woodworking company was in the butter churning arena. He was turned off from baseball by all of the negatives associated with the sport.

Flash-forward to the present: The Hillerich & Bradsby Co. is the maker of the Louisville Slugger bat, one of 29 bat-making companies licensed by, for use in, Major League Baseball. It’s a fifth-generation company with the sixth-generation in the wings: Quinn, 18, is a recent high school graduate who is an intern at the downtown Louisville-based company.

The company makes about 2 million wooden bats annually, including about 800,000 mini bats. The production total for full-size bats has gone up over the past couple of years, company officials said.

Louisville Slugger bats are used by about 60 percent of the major leaguers, including Derek Jeter, Josh Hamilton, Prince Fielder, Dustin Pedroia and Joey Votto, among others.

Louisville Slugger was also the bat-of-choice for Babe Ruth, Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle, as well as Cal Ripken Jr., Johnny Bench and Stan Musial.

More than 8,000 major leaguers have stepped into the batter’s box gripping a Louisville Slugger.

“The players are part of the family,” said PJ Shelley, tour and programming director for the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory.

History and statistics

The Hillerich family came to the U.S. from Germany in 1842, first landing in Baltimore and then moving to Louisville. The Hillerich & Bradsby Co. is now such a local institution that souvenirs sporting the Louisville Slugger name and logo are even sold at the airport.

Other historical memories are:

- In 1905, Honus Wagner signed a contract giving J.F. Hillerich & Son permission to use his autograph on Louisville Slugger bats.

- In 1908, Ty Cobb signs a contract with J.F. Hillerich & Son for autographed Louisville Slugger bats.

- In 1946, John A. “Bud” Hillerich, who made the company’s first bat, dies.

- In 1996, the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory opened.

- In 2006, Louisville Slugger teams up with Major League Baseball to produce pink bats for players to use on Mother’s Day, raising money for breast cancer research. Players using pink bats are actually given two different pink bats – one with their name engraved on it, and another with their mom’s name emblazoned on the bat.

- In 2011, the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory welcomed its 3 millionth guest during its 15th anniversary celebration.

- In 2013, officials predict 250,000 will visit the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, up from 240,000 people in 2012.

Respect for the lumber

Shelley, a 37-year-old New York Yankees fan, has been working for Louisville Slugger for almost five years, coming here after working in Cooperstown, N.Y., at the National Baseball Hall of Fame for six years.

He said he has a great job – his smile and the enthusiasm in his voice proves it.

“The best part of the job is getting to meet the ballplayers who visit the factory in Louisville,” Shelley said. “It’s neat to see the respect that they have for the company, the brand, the product.”

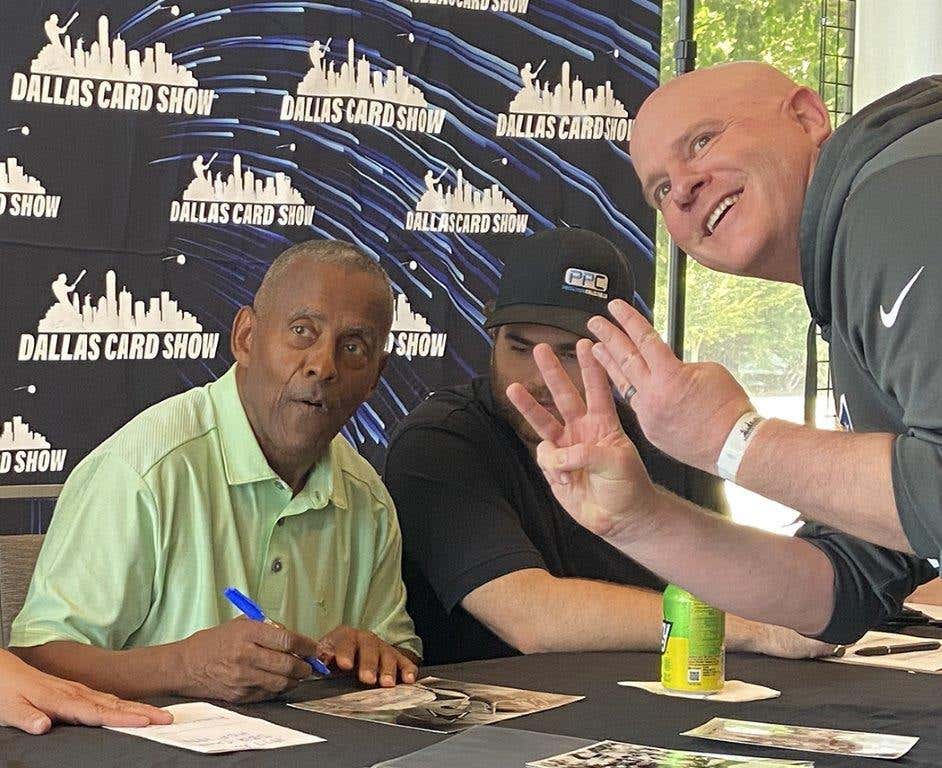

For instance, Don Kessinger visited on July 4.

“The players, current and retired, show such reverence for the company, for the bats. That makes me feel good working for this company,” Shelley said.

Craig Biggio came to Louisville on Sept. 24, 2007, days before what was to be his last Major League game. He shook hands with all factory employees that day, thanking them for what they did for his career. Biggio also autographed a bat for every person in the Louisville Slugger factory.

The company then made Biggio a hand-turned bat, which he used Sept. 27, marking the last hand-turned bat used in a Major League game.

Biggio went 1-for-3 with two RBIs, using the hand-turned bat, in Houston’s 8-5 win in Cincinnati.

So where is that Biggio-used, hand-turned bat?

“I don’t know; it’s not in our collection,” Shelley said.

Biggio joins an amazing array of athletes, celebrities and dignitaries who have visited the museum, including Hank Aaron, Muhammad Ali, Orlando Bloom, President George W. Bush, President Clinton, Geena Davis, Rudy Giuliani, Paul Hornung, Bobby Hull, Ken Norton, Pete Rose, George Steinbrenner and Ted Williams.

A bat of all major leaguers who have signed contracts with Louisville Slugger, which totals more than 8,000, is now housed in “The Vault” inside the museum.

Bats from Babe Ruth’s era often were made from hickory. Today’s bats are mostly either ash or maple. The wood comes from Pennsylvania and New York, as the company owns several thousand acres of forestland and has contracts with land owners in that region.

“We consider those to be the best trees in the world to make baseball bats,” Shelley said. “It’s a combination of the geography, the soil, the sunlight, the weather. Everything is perfect.

“For a good ash tree, you want it to grow straight and tall, so the grain lines are straight, which will lead to a bat that the balls will come off of really well.”

Trees grow about 80 years before they are cut for their use in Major League Baseball, and the company gets about 60-80 bats per tree.

The outside of the log is used for bats, as that’s where the strongest wood is found. The company sells the “inside” wood to furniture companies.

The sawdust generated at the factory while making bats goes to, well, the turkeys.

“Every three or four days, a local turkey farmer comes by and takes about 30,000 pounds of the sawdust to his farm in Indiana, using it for bedding for his turkeys,” Shelley said. “So, some lucky turkey is sleeping on, oh, Alex Rios’ wood shavings tonight.”

In addition to major leaguers’ bats, the company also produces numerous commemorative bats, such as for the MLB All-Star Game, the World Series, the Hall of Fame, the opening of new stadiums and more.

Shelley said minor and major leaguers visit the factory “fairly frequently,” particularly minor leaguers.

“Most players don’t stick with the same model bat throughout their career; they often change the weight, the length, the model, etc. The two extremes to that are Derek Jeter, who has used the same model bat his entire career; and Hanley Ramirez, who changes his model multiple times during the season,” Shelley said.

Alex Rodriguez, meanwhile, uses a 34-ounce bat in batting practice and a 32-ounce bat in games.

Most major leaguers will used 80-120 bats per season. That total for National League pitchers is significantly less, Shelley said.

Shelley was not sure who uses the most bats per season, although he did say Johnny Damon would be high on the bats-used-per-season list, mostly because he broke a lot of bats.

Hitting the facts

Here are more bat chips (or tidbits) from the Louisville Slugger Museum & Factory, with its 16,000 square feet of exhibit and archive space:

- In addition to seeing first-hand how bats are made, the museum features a variety of hands-on exhibits and more. Visitors can stand as if they were the umpire for a 90 mph fastball or have their photo taken with a game-used Mickey Mantle bat from 1961 (see above). There also is an inspirational short film inside the 90-person theater.

- The signature wall showcases more than 6,000 autographs – from Ruth and DiMaggio to Jeter and Ripken – burned into white ash wood.

- A Babe Ruth-used bat shows carvings that Ruth made into the bat for every home run he hit with that bat.

- Hillerich & Bradsby offers 12 different finishes to the Major League Baseball player. Colors vary. All of the finishes are water-based lacquers and have no relevance in the strength of the wood.

- Ted Williams once complained about some of his bats, questioning the way the handles tapered on the bats. Ultimately, it was determined that the bats in question were 5/1000ths of an inch off.

- Williams also once picked out a bat that was one-half ounce heavier than others after company officials gave him five identical bats and one slightly heavier.

- Inside the souvenir store, visitors can order bats with their name engraved on them. Plus, the store features a small section of autographed memorabilia, including signed bats and signed baseballs for sale. In mid-July, the store was selling an autographed Babe Ruth baseball.

- Museum hours: Monday through Saturday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sundays from noon to 5 p.m. From July through mid-August, the museum is open until 6 p.m. Admission is $11 for adults, $10 for seniors (60+), $6 for children (6-12) and free for children 5 and under.

- For more information, call (502) 588-7228, or visit www.sluggermuseum.com.

Ross Forman is a freelance contributor to SCD. He can be reached at Rossco814@aol.com.