Memorabilia

An Inside Look at the Major League Baseball Authentication Program

By Greg Bates

Every child who goes to a Major League Baseball game has dreams of heading home with a ball.

However, the chance of getting a coveted souvenir by having a player throw a ball into the crowd or catching a foul ball or home run is pretty rare.

Major League Baseball (MLB) has designed an easier, less stressful way for fans of any age to acquire genuine, game-used products. Each team collects baseballs, bases, broken bats, lineup cards and other items from every game and has them available for purchase.

“I look back on my youth and I would have loved to have purchased a game-used ball from my first baseball game,” said Michael Posner, licensing manager, MLB Authentication Program. “If I ever decide to have a family, I can take them to their first game and be able to commemorate that in some way, shape or form with something that was actually in the game.”

The MLB Authentication Program has become a valuable tool for the league, its 30 teams and baseball fans all around the world.

It’s a way to preserve artifacts by documenting the rich history of the game, ensure fans enjoy their experience at a game and help prevent fraudulent activity in the collecting industry. It wasn’t always like that.

The program started in 2001 as a spinoff from the FBI investigation “Operation Bullpen.” In the late 1990s, San Diego Padres great Tony Gwynn happened to be in the team store at Qualcomm Stadium and noticed some autographed baseballs on sale. Gwynn was adamant he didn’t sign the items, and an investigation ensued.

Operation Bullpen led to more than 30 successful prosecutions for memorabilia fraud. It might have been the best thing to happen to the game of memorabilia collecting.

“Operation Bullpen determined that 75 percent of all autographs currently in the market at that time were fake,” Posner said. “From our standpoint, [with MLB] being three-quarters of the sports memorabilia, we obviously had to take a leadership position, and there really wasn’t anything in place to protect the fans, the players and the clubs. The idea of the authentication program evolved from that.”

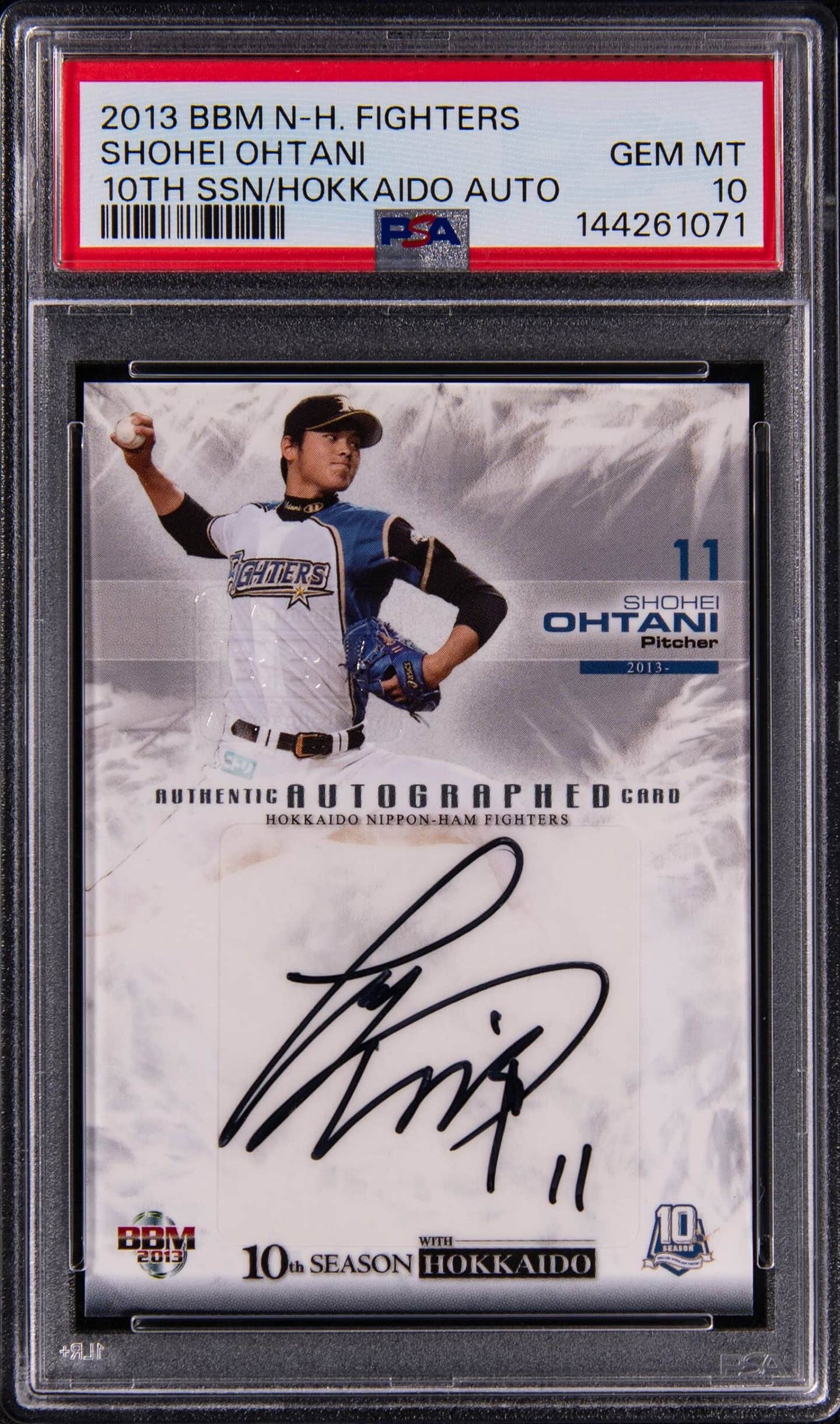

An important way in making sure autographs weren’t going to be forged in the future, MLB wanted to eliminate certificates of authenticity. People who purchase baseball memorabilia from companies or individuals generally receive a piece of paper “guaranteeing” the product that was purchased is genuine. With the MLB Authentication Program, tamper-proof holograms are placed on all items to ensure customers are getting the real deal.

“They’re not rolling the dice that this is a jersey that someone bought at a sporting goods store and threw it in the dirt in the backyard and then tried to pass it off as the real thing,” Posner said. “It’s taken a lot of that guessing out.”

It’s now a lot less stressful on the consumer.

“Baseball’s taken a great expense to try and make sure that fans aren’t getting ripped off in the marketplace,” said Marc Himelstein, director, authentics for the Detroit Tigers. “If you go buy something from the team or from mlb.com, you know it’s legitimate. If you go to your local baseball card store or a store in the mall or eBay, you’re taking your chances. A certificate of authenticity, I tell people daily, is worthless. Any guy with a computer can sit there with their baseball and practice writing some player’s name until it’s good enough to put it online and say it’s Bill’s Card Shop in some state the player doesn’t play that you couldn’t verify and try to sell it on eBay. Once you start talking to people and explaining it to them, you can see the light bulb go on in their head. ‘Oh yeah, you’re right. I could do that.’ ”

A first-hand account

MLB authenticates between 500,000 and 600,000 items per year and, as of late July, has logged more than 4.8 million unique items since the program got started 13 years ago.

The MLB authentication process is a two-prong attack. It is a witness in collecting game-used items and autographs signed by players. To ensure the program runs properly, MLB uses an objective third-party company, Authenticators Inc., to hire and manage the personnel. The authenticators are either active or retired law enforcement officers, and each potential authenticator goes through a thorough background check before being hired. Accuracy is the top priority for every authenticator.

“You can’t apply for the job,” Posner said. “You could be the biggest fan in the world, know everything that’s going on but it’s literally a job that we want to vet people in. We don’t want to have fans in the clubhouse because the access they get is unprecedented for any sport.”

Each of the 30 MLB teams has three to five authenticators – there are 135 total – who make sure game-used items are legitimate. Every item collected or signed has to be witnessed first-hand by an authenticator.

“I always preach this: You’re there to record history as an authenticator,” Posner said. “You have one job; your job is to ensure that everything you’re putting a hologram on is absolutely 100 percent the real deal. You’re there to watch a game and record the history. This is a sport, more than any other of the major sports, that is about its history.”

Authenticators are present at all 2,430 games regular season games, plus postseason, All-Star festivities and spring training games.

In-game collection

Sitting in the camera well down the first-base line nearest home plate at Busch Stadium, Jim Welby doesn’t miss a single play during a St. Louis Cardinals game. That’s what he’s paid to do.

As one of three authenticators for the Cardinals, Welby has perfected his job over the years. A former city of St. Louis police officer who retired as a sergeant two years ago after 35 years of service, Welby worked security for the team for about 20 years before landing the authentication job. While doing security, Welby had worked a number of postseason games and mingled with MLB representatives on hand.

“Somewhere down the line they liked my attentiveness to duties and responsibilities, and when the time came I got a phone call and was asked if would be interested in the (authentication) position,” the 61-year-old said.

Welby tries to split up the Cardinals’ 81 home games throughout the season evenly with the other two authenticators – one who is a current law enforcement officer and the other who is retired.

For the games Welby works, he will start his day by reviewing information sent to authenticators from the MLB authentication office in New York.

“Take for example the Boston Red Sox, I will look and see if any of their players are reaching a particular milestone. It might be their 500th home run or 1,000th hit, whatever it might be,” Welby said. “I’ll also check for our home team as well. I want to see if there’s anything that could possibly happen that we know will happen eventually, and I’ll be prepared for that.”

Wearing casual business attire for a game, Welby arrives at the ballpark and checks in with both clubhouses. He speaks with the clubhouse manager for the opposing team to see if there are any requests for special items. Maybe a player just got called up from the minor leagues and is going to get into his first game. If that player gets his first career hit, the team will want to acquire that baseball.

When the game gets under way, Welby is solely focused on the task at hand. If a baseball goes into the stands or out of Welby’s sight, that item can’t be authenticated.

“This way we know that every ball that comes off the field is an actual game-used ball,” Posner said. “It’s not an opinion, it’s based on what the authenticator sees.”

Any baseball that stays in the ballpark and is discarded – via a passed ball, fouled back into the netting, the pitcher wants a new ball – the batboy retrieves the ball from the home plate umpire and will then roll or hand it to Welby.

“We literally can capture all the information of what happened with that ball right before it came off,” Posner said. “In some cases, we can do a longer trail and go maybe two or three batters in.”

Welby will document the pitcher, batter, inning and the reason the ball came out of play. He will then apply a hologram sticker to the ball. The hologram is tamper-proof and has a unique serial number only for that item. Anyone who acquires a game-used product can go on mlb.com/authentication and cross reference the item with the database and find out all the information.

“If someone tries to take the hologram off an item and try to move it to something else, that hologram will destroy itself,” Posner said. “Having that hologram ensures a much better experience for the customer.”

Welby places each ball into a giant Ziploc bag for storage. In St. Louis, the authenticators retain the balls until about the sixth inning when a team representative comes down to retrieve the items. The team is given all the documentation it needs to be able to put the ball up for sale.

At the end of the game, Welby takes the balls collected from the seventh inning on and places them into a secure locker. In all, Welby generally gathers around 24 baseballs for the Cardinals – sometimes more for special occasions – who sell them at their two stores, one at Busch Stadium and the other across the street from the field. According to Posner, it’s typical for each MLB club to collect 24-36 balls per game. (Game-used balls from the 2014 season are listed on the Cardinals’ website for $34.99 each.)

Welby also grabs all three bases from the grounds crew, cleans them up a bit, applies a hologram and writes some specifics about each base (primarily the base location and date) on the back. Welby might have also collected some shattered bats – he averages about two per game – which will be authenticated. He always takes the lineup cards from each team, too.

After being authenticated, the information for each item is entered into a handheld scanner and uploaded wirelessly to the main system for MLB approval. Within 24 hours of an event, items can be verified online at mlb.com/authentication. According to Posner, MLB is constantly working on improving technology to track every pitch in every game.

Another important chunk of Welby’s job (and every authenticator) is verifying and authenticating player autographs. According to Posner, autographed baseballs are the most authenticated items, followed by game-used baseballs.

When Cardinals players have team signings either in private at Busch Stadium or public shows around St. Louis, an authenticator is always present. If a player autographs an item without an authenticator witnessing the signing, it won’t receive a hologram. At a private player signing, the only people who usually attend are the player, authenticator and the team’s authentication director.

Welby and his authentication partners are generally busy a couple times a month for scheduled signings, most of the time at the stadium.

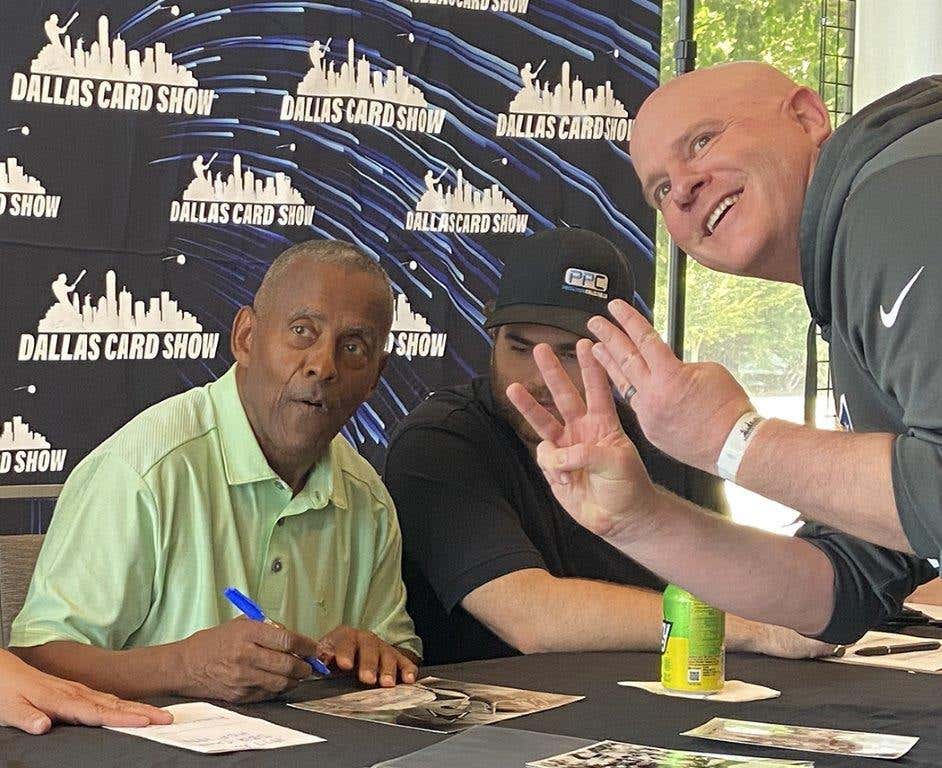

In conjunction with the authentication program, MLB has a number of licensed partners: Steiner Sports, Fanatics Authentics, Highland Mint and MLB Alumni. Those companies have exclusive rights to hold autograph sessions and have the items authenticated by MLB. According to Posner, there are a lot of companies that want to be partners, but MLB wants to work with the right partners that have a good history of being straight dealers and will properly represent the program.

“The partners that are with us in the industry obviously want to be part of this whole process that we’ve started,” Posner said. “That is really the bread-and-butter of the program, if you will, because that was mostly the impetus for us starting in the first place.”

One of most interesting things, in Posner’s opinion, that’s authenticated and sold at ballparks nationwide is dirt. Each team collects samples or even buckets that are authenticated just like a baseball or base. Selling dirt from the shortstop area at stadiums has been a hot commodity this season with the retirement of New York Yankees legend Derek Jeter. MLB representatives scooped up brown gold from the Target Field infield following the All-Star Game in July.

Booming business at the ballpark

Every item that is collected and authenticated during a game is property of the individual team. However, MLB and even the Hall of Fame will sometimes request certain items if a major milestone was met such as a 3,000th hit, 500th home run or a no-hitter.

Since the teams own the products, they generally sell the items. In steps Marc Himelstein. He is in his seventh season running the authentics business for the Detroit Tigers. Every MLB club has a person with a job similar to Himelstein’s.

One significant part of Himelstein’s job is being the main team liaison for the three longtime authenticators for the Tigers. He works closely with the authenticators to make sure the team gets everything it needs.

“It’s a lot of communication and coordination with the MLB authenticators, along with our guys that work in the clubhouse,” Himelstein said. “We prepare the best we can, but you never know when a milestone is going to happen.”

With the Tigers having the last three AL MVP and Cy Young Award winners on their roster, Himelstein has to always be on his toes because Justin Verlander might throw another no-hitter or Miguel Cabrera could hit four home runs in a game.

Himelstein also tries to prepare for the unexpected when opposing teams come to town. In early August, he was bracing for the Yankees’ arrival at the end of the month since Jeter had recently moved into sixth place on the all-time hit list.

During a typical home game at Comerica Park, Himelstein works in a large authentics kiosk in the park’s concourse selling game-used items. There is also a large section in the Tigers’ team store, The D Shop, and four small stores at Comerica that sell strictly autographed baseballs.

Himelstein monitors each game on television, and in the third inning, he’ll head down to the Tigers’ dugout and collect baseballs from the authenticator. Usually at that point in the game there are 10-12 balls ready to pick up. It’s a common practice for teams to collect balls during a game.

It doesn’t take long for the baseballs to be on sale in the stores and kiosks. Himelstein will tweet out that balls are available, and there is usually a steady crowd of fans who purchase items. People are able to preorder or reserve a baseball or bases weeks in advance, and Himelstein actually prefers fans go that route.

According to Himelstein, on average 33 baseballs are collected per game at Comerica Park, which equates to 2,500 per year. When Himelstein – who will even save items for the archives of longtime Tigers owner Mike Ilitch to preserve team history – first started his job seven years ago, he was collecting just six balls per game and they were just classified as game-used items. Now, every discarded ball is taken and is authenticated to the pitch.

“It’s a way we’ve tried to push the envelope in the way we think,” Himelstein said.

Himelstein assigns the prices for each item that goes on sale. He believes he has a firm grasp on how much he should charge. It’s a team-by-team decision how much items are sold for.

At Himelstein’s shops, a regular game-used baseball is $35. The price of a ball can spike if say either superstar Miguel Cabrera or Justin Verlander was known to have been involved on a play. Bases go for $200; again, if something significant happens in a game, the price could go up. Broken bats, depending on condition of break and whose bat it belongs to, can range from $150 to a couple thousand dollars. However, most range from $300-$500, Himelstein said.

All 30 MLB teams have taken advantage of the authentication program – selling on either shop.mlb.com and auction.mlb.com or both – and most have kiosks or walk-in stores at the ballpark to purchase game-used items. Since every MLB club sells its own items, it’s up to them where the money is allocated. However, all 30 teams participate in charitable fundraising throughout the year.

Himelstein is a big proponent of the authentication program and all it has to offer.

“This has really become the pre-eminent way to authenticate current or living baseball players,” Himelstein said. “You know that it’s tamper proof, it can’t be duplicated. You can look it up in the system for the next thousand years and it will be there. The hologram will be there showing that item was signed by Torii Hunter, it was used by Torii Hunter. No one else can really offer that.”

The program is gaining traction, and more fans are starting to realize its impact on the sport and the collecting industry.

“We get a lot of fans who are down around where we are located during the game and they’ll come up and say, ‘What are you doing with those balls?’ ” Welby said.

“It’s kind of nice to tell them a little bit about it and get the word out. I think the fans are even fascinated with the process. Major League Baseball has done a great job initiating this program and developing it and fine tuning things as we went along. I think we’re offering something to the fans that’s very unique in sports merchandise.”

Greg Bates is a freelance contributor to SCD. He can be reached at gregabates@gmail.com.