Collector Stories

Olbermann Proof Series Part III: The calm before the storm

By 1970, baseball card collecting by adults was no longer a secret. The landscape was populated by at least four “dealers” who earned their livelihood buying cards – mostly directly from what was then Topps Chewing Gum – and selling them via mail order. The working relationships had begun to allow cards the public had never seen in Topps’ annual retail blitz to find their way into the primordial “hobby.”

Already, a 1967 “proof” card showing Roger Maris with the Yankees instead of the Cardinals had made it “out” – and whether or not anybody realized it, the hobby genre of proof collecting had been born. Although it would be 20 years before enthusiasts even knew of the existence of some of

the real gems, like the 1968 cards of Bob Gibson and Tom Seaver pitching left-handed, the pattern had now been established. And as the major leagues again expanded (100 more roster spots in 1969 than the year before), the necessity for constant vigilance, and frequent change, between the test versions of each card, the proofs and the final versions that showed up in the stores, made the number of varieties between the two grow and grow.

1970 – Four player photos were swapped out after late trades.

The proofs of No. 359 Phil Roof and No. 437 Danny Cater show them in Oakland A’s batting poses, No. 24 Dick Selma shows him with the Cubs, and No. 644 Gerry Nyman depicts him with the White Sox, the latter two each in follow-through pitching poses. The issued cards show capless head shots, and list each player with his new club (Roof with the Pilots, Cater with the Yankees, Selma with the Phillies and Nyman with the White Sox).

There are also three intriguing variations for the team cards of the Red Sox (No. 563), Cubs (No. 593) and Pirates (No. 608). The issued cards identify each team by city and club name; the proofs give only the club name.

Since Topps also produced a set of test “cloth” stickers featuring about half of the 2nd Series (with three photos differing from the issued cards), it’s long been assumed that these might some day show up on a proof sheet somewhere. But, 35 years later, No. 139 Rich Nye (Cubs pitching pose instead of capless portrait), No. 178 Denny Lemaster (pitching pose instead of portrait) and No. 257 Dennis Higgins (Senators pitching pose instead of capless portrait) still haven’t surfaced.

Some 1970 items that exist in enormous quantities are thin, square-edged blank-backed proofs of the large Super Baseball set. These have been so common so long that I bought some of these sheets at an antiques shop in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., circa 1972 (the 1971 Super proofs are a little less frequently seen, but still widely available). There are no varieties known among the Super proofs.

1971 – The 6th Series Proof sheets – of which as many as a half dozen made it into the hobby – contain no fewer than five photos that did not appear on the issued cards:

No. 651 Jerry Robertson shows him in a pitching pose, in a Detroit uniform, with the team identified as the Tigers. The issued card is a portrait of Robertson with the cap hastily airbrushed to a light blue, and it gives his team as the Mets.

No. 663 Marv Staehle and No. 731 Jim Qualls shows each with the Expos, in Montreal uniforms. The issued cards are again portraits with painted-over caps, with the team designations changed (Staehle to the Braves, Qualls to the Reds).

No. 665 Ron Swoboda shows him with the Mets. Again, the issued card has a portrait, this time with an airbrushed Expos logo, and Montreal team designation.

And No. 723 Vicente Romo shows him, in proof form, with the Red Sox. For the issued card, the same photograph is enlarged to show only his head, with the cap airbrushed and the team designated as the White Sox.

There are also several minor variations on the 1st Series sheet, most notably the card of the Yankees Rookies (No. 111). The proof identifies pitcher Loyd Colson only as “Loyd,” a mistake obviously corrected on the issued card.

Collector Shuchart reports a novel twist to some of this year’s proof sheets: a number exist with fully printed backs. But, those backs turn up only on “progressive” proofs (not the full-color ones) and only on those that include the “blue” tests (blue; blue and yellow; blue, red and yellow).

1972 – Late trades again created four more photograph variations, all of them on the 2nd Series sheet, most notably of No. 240 Rich Allen, who goes from a Dodgers portrait in the proof, to the same profile shot used in his 1970 card and a White Sox designation on the issued card.

The other changes are for No. 161 Brock Davis (proof: Cubs, batting shot; issued: Brewers, capless portrait), No. 175 Tom Haller (proof: Dodgers, catching pose; issued: Tigers, no logo visible on cap) and No. 204 Tommy Helms (proof: Reds, fielding shot; issued: Astros, capless portrait).

In 1972, Dan Dischley, editor of the aforementioned The Trader Speaks, told me that his friend, the late pioneer collector and Topps Sports Editor Bill Haber, had sent him an “advance set” of the 1972 cards, and that there were many 5th and 6th Series cards that varied significantly from the ones in the packs. Dischley insisted that among these was a card of Chico Ruiz, an Angels’ infielder who had been killed in an off-season automobile accident.

But a Ruiz card – which would be the earliest (but hardly the only) known example of a player being “pulled” from a Topps set and extant only in proof form – has never turned up. At the 1989 Guernsey’s auction, a complete “set” of proof sheets was sold as Lot BB 188 (for $3,250), and a close examination of each sheet turned up no Ruiz card and no significant variations besides the Allen, Davis, Haller, and Helms photo switches. There were three “blank checklists” (for the 3rd, 5th, and 6th Series), and color variations on two 2nd Series Rookie Cards (No. 141 Mets and No. 257 Tigers), and many of the Cubs players, and Boyhood Photos, cards.

From that auction, however, we know that the four changed photo proofs are not unique. At least one copy of each was known to exist before the sale; one copy of each was included in the “complete set” lot, and Lot BB 170 consisted of another 1972 sheet with the Haller and Helms proof variations.

There is also a bizarre error on the proof of No. 401 Jim Nash that was corrected before the issued cards were produced: a “Topps Rookie Award” trophy. Nash was, by 1972, six years removed from actually receiving that recognition.

1973 – Only two photo swaps are known, both from the 1st Series sheet.

The proofs show No. 107 Phil Hennigan in an Indians’ uniform (the issued card has him with the Mets), and No. 132 Matty Alou with the A’s (issued with the Yankees).

Only two other photographs were significantly altered. The issued card of No. 355 Mike Marshall shows him with a Montreal Expos logo painted over his cap, in a semi-profile pose. But the proof variation has a bat over his shoulder, and the traces of a logo of the minor league Toledo Mudhens on his left sleeve. Logo and bat were excised from the issued card.

Similarly, both the proof and issued version of the No. 606 Rookies card depicting Jorge Roque show him with an airbrushed Montreal logo on his cap. But on the proof card, the neck piping of his original St. Louis Cardinals’ uniform is still visible. And No. 175 Frank Robinson – with the Dodgers lettering weakly airbrushed off his uniform in the issued version – exists in proof form with that lettering still legible.

But there are two intriguing smaller proof variations which reflect Topps’ milestone decision that year to switch from the “series” format to the “all at once” method of distribution. The same sheet that contains the Alou and Hennigan cards also contains checklist cards marked “1973/First Series” and “1973/Second Series.” The issued cards don’t refer to series, just the numbers covered by the checklist.

Most of the country got its 1973 Topps cards series by series, month by month, just as it had since 1952. But in Florida and California, the cards were issued all at once, experimentally and (obviously) successfully. Thus the references to “Series” would have defeated the marketing test, and the issued cards were changed to delete them.

Several other minor variations exist, including the tinting of the coaches’ photos on nearly all of the managers’ cards.

1974 – After a run of five years out of six in which there were large numbers of photo variations, this was a set with none – and the vast majority of proofs consisted of fixing very big mistakes.

There are three team changes. As one might expect from the issued No. 258 Jerry Morales showing him in a Padres uniform but listing him with the Cubs, and No. 241 Glenn Beckert showing him in a Cubs uniform but listing him with the Padres (or, in printed error form, “Washington, Nat’l Lea.”), each exists in proof form with his pre-trade team. So, too, does No. 157 Vic Harris (Cubs on the issued card), which shows him with the Rangers on the proof. But in each case, the photos are identical.

The other two dozen proof variations are simple, and ultimately corrected, blunders. No. 141 Pat Bourque is shown in the same A’s batting pose as on the issued card, but inexplicably lists him with the Red Sox. Same for the cap-less shot of Bud Harrelson on No. 380, which identifies the longtime Mets shortstop with the Braves. Bourque never played for Boston, nor Harrelson for Atlanta.

There’s a third outstanding error. The head shot of Joe Niekro on card No. 504 has an airbrushed Atlanta logo on his cap, and shows Niekro looking to his right. The proof version has the identical photo reversed: Niekro is looking to his left, and the airbrushed logo is backward.

The remaining variations are obscure – background and outlining colors are different. But, in light of what’s probably the most famous mistake in Topps history, some of those other 1974s are interesting.

This was the season Topps jumped the gun on the planned move of the San Diego Padres, and issued the 14 lower-numbered Padres (and the No. 599 rookie card featuring Padre Dave Freisleben) in two varieties: San Diego or “Washington, Nat’l Lea.” The proof cards of the Padres up to number 387 all list the team correctly (no “Washington” proof has ever been found), but the color scheme for the lettering is all different. Instead of black on a brownish orange, they’re all white on brown – not a mistake as such, but a design change (and paralleled by other aesthetic changes for other teams as well).

The proof cards, as ever, give considerable insight to baseball card history. The Topps Vault auctioned a 1974 proof sheet on eBay in 2003, and all the Padres players on it are listed with San Diego – and are thus covered by the hand-markings of the set editor, insisting that they be changed to Washington. Just to further clarify what was happening at Topps HQ, this proof sheet is, as most were, dated – marked “Dec. 6, 1973” – and thus indicating what kind of chaos had enveloped the card company less than three months before the cards were due in stores.

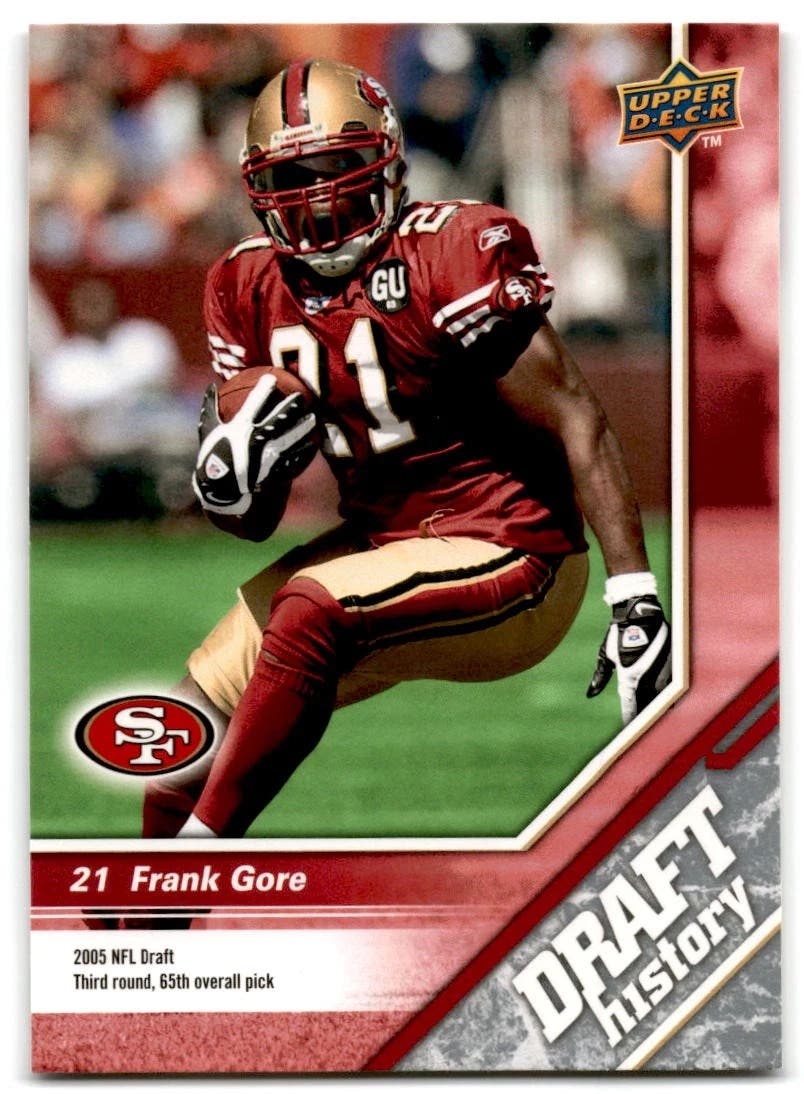

It should be mentioned in passing that 1974 is the year of the only known unissued Topps football proof. Though he was left out of the issued set in a contract dispute, a card of Joe Namath exists in proof form, and at least one copy has survived.

1975 – Another disappointing year for the proof collector.

There are no reported team or photo variations – just a series of corrections to the colors of some of the lettering on the Leaders, World Series cards and the like. Also, one sheet of 66 cards was proofed without the facsimile autographs, at least one more was proofed with many of those autographs (including No. 370 Tom Seaver) appear in different positions than on the issued cards, and the airbrush jobs on the cards of Ross Grimsley (No. 458) and Ken Boswell (No. 479) were improved upon in the final product.

1976 – Again, just a handful of variations between the proof and issued cards, although there is one intriguing photo switch and an unlikely spelling error.

Most of the two dozen or so changes are merely stylistic (the issued cards of Giants show the players’ names in yellow lettering on a dark-green background; three of the proofs show them in yellow lettering on an olive background). There are similar color changes for other players’ names, and in the case of No. 600 Seaver, the name is absent entirely.

But somebody didn’t like the original version of No. 63 Bobby Darwin. Traded in mid-season of 1975 from Minnesota to Milwaukee, Darwin’s proof card shows him in a Twins batting helmet repainted to resemble a Brewers helmet. Yet the issued card shows a different head shot, in a regular cap, also airbrushed to reflect the trade. The curiosity here is that the batting helmet shot seems a far more convincing touch-up job than does the issued cap shot.

Also, the card of No. 9 Paul Lindblad – by then in his 11th consecutive Topps set – has his name misspelled in the proof version (“Linblad.”) By this point, Topps appeared somewhat hexed by Lindblad. The proof of his first card (1966) apparently exists without his position listed. He’s also on one of the 1975 proofs known without an autograph.

The Brewers’ team card, which shows an inset photo of newly-hired manager Alex Grammas, exists in proof form with no manager shown.

At least a half dozen of the Darwin proofs are known to exist – one was on a sheet auctioned by Guernsey’s in 1989, and a second appears to have been cut from another partial sheet sold in the same sale. In December 2007, Bruce Yeko, the man behind the powerhouse mail-order firm of the 1960s and 1970s, Wholesale Cards, put his copy up for auction on eBay, explaining he’d been given it personally by Topps design wizard Woody Gelman more than three decades ago.

If it looked like the late 1970s were going to be barren times for proof collectors, history would quickly change all that.

If arbitrator Peter Seitz’s decision permitting players to walk away from their teams and sell their services to the highest bidder was to alter the nature of the game itself, it would throw the production of Topps baseball cards into absolute chaos.

The upcoming fourth part of our series on Topps proofs will be devoted entirely to the year 1977, with no fewer than 24 major variation cards, including the first three confirmed cases of Topps literally “pulling” players from the set and never issuing their cards, plus the most famous proof of them all.