What's It Worth?

For Mike Piazza, the HOF was Worth the Wait

By Robert Grayson

Mike Piazza is a patient man. After all, he’s had a lot of practice.

Though he’s now recognized as one of baseball’s greatest backstops, the road to baseball immortality was long, winding and often bumpy for the Norristown, Pa., native. So when Piazza failed to make it into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown on his first three tries, the 12-time All-Star didn’t despair.

Instead, he responded each time by rattling off a list of other major league standouts who each hit a snag on the way to baseball’s esteemed shrine and didn’t get in as quickly as fans might have expected. That list included the Yankee Clipper Joe DiMaggio, who wasn’t inducted until his fourth try, and fellow catchers Yogi Berra, voted in on his second year of eligibility, and Roy Campanella, who entered Cooperstown on his fifth try. The list was little comfort to his many fans, but the hard-nosed receiver knew good things come to those who wait, and he was right.

The Baseball Writers Association of America voted Piazza into the Baseball Hall of Fame this year, on his fourth try. While the wait for the results of the 2016 vote by the writers was a bit of a “nail-biter” for him, Piazza always remained optimistic. “Being a baseball history buff and knowing how many great players had to wait years to get into the Hall of Fame put everything into perspective,” he maintains. Now that he’s in the shrine, Piazza says he’s “simply overwhelmed” by the honor.

Like so many other youngsters, Piazza had a boyhood dream of playing in the big leagues. The difference between him and most others who harbored that ambition was that his father took young Mike’s dream seriously enough to build a batting cage in the backyard of the family’s home. Vince Piazza even put up lights so his son could practice hitting at night. The younger Piazza remembers his dad working with him on hitting every day.

“He was probably closer to going over the top than most parents today. Nonetheless, he was able to see that baseball was a passion I had. He knew I was able to handle the workload and I responded to that,” the 1993 National League Rookie of the Year recalls. “My father was so instrumental in getting me to focus. I think that’s something we struggle with today because you don’t want to be so intense, but you also want kids to focus on something and get them motivated.”

The elder Piazza had once dreamt of playing in the majors himself, but he had to leave school at 16 to help support his family. So when his son Mike showed an interest in the game and a talent for it, Vince Piazza began to consider the possibilities of his boy making it to The Show.

Mike’s dad, who had loved the game his whole life, had a boyhood friend, Tommy Lasorda, who had not only played in the majors for a short time but had become manager of the Los Angeles Dodgers in September 1976. That was just about the time young Mike Piazza started belting a baseball in his backyard batting cage.

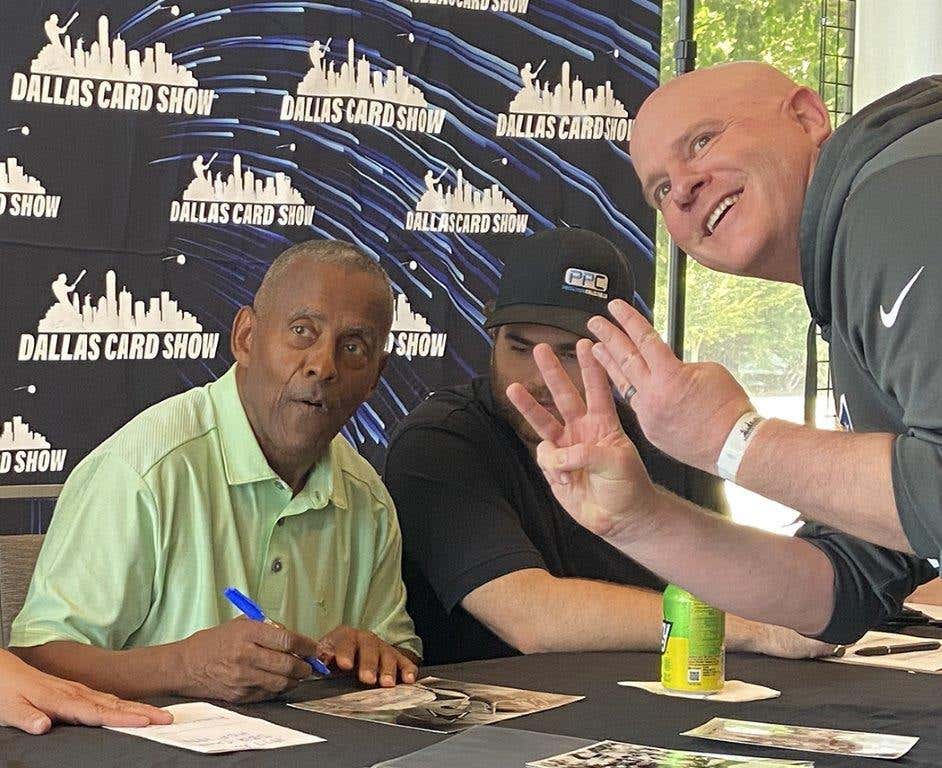

Through Lasorda, Vince Piazza made many friends in baseball, including longtime Dodgers scout Eddie Liberatore, who also lived in Norristown. Liberatore knew lots of current and former players, including DiMaggio and Ted Williams. Mike Piazza recalls that when the future Hall of Famer was 16 years old in 1985, Williams came to sign autographs at a baseball card show at the George Washington Motor Inn in nearby King of Prussia, Pa.

“I grew up reading Ted Williams’s book, The Science of Hitting. I think I memorized it,” he says with a smile. Liberatore urged Mike’s dad to bring his son to the baseball card show to meet Williams. Mike was thrilled at the prospect of seeing his hitting idol in person.

When the Piazzas got to the baseball card show, Mike realized that Liberatore had mentioned to Williams that Vince was the friend he had talked about. “Eddie Liberatore had told Ted Williams, ‘Vince has a boy who is a pretty good hitter and has a batting cage in his backyard,’ ” the new Hall of Famer notes. “Ted’s response was ‘Let’s go see him hit.’ ” And, to the young Piazza’s amazement, the next morning the Splendid Splinter was at his house.

Williams watched Mike hit for quite some time and was impressed with his strength, power and keen batting eye. He gave the youngster some tips, but said, “This kid really looks good,” the still-starstruck Piazza remembers from that surreal day at his house. “He (Williams) sat at my kitchen table and signed my beat-up copy of The Science of Hitting. I still have it.”

At the time, Piazza was playing first base for the Phoenixville (Pa.) High School baseball team. In June 1985, the Philadelphia Inquirer had called him the “area’s most feared long-ball hitter.” But in the mid-1980s few pro teams were excited about a power-hitting first baseman. Young first-base prospects could be found all around the country, and Mike was a slow runner. Nevertheless, in his senior year in high school in 1986, Piazza hit .442 with 11 home runs, and he wanted a shot at a big league baseball career.

He spent two years in college, hitting .364 for the Miami-Dade North Community College Falcons in 1988. Yet, there was still little interest in him from the pros. That’s when the well-documented series of events started to unfold that led to Mike’s eventual stardom in the majors.

Lasorda persuaded the Dodgers to draft Piazza. They took their time selecting him, not making the move until the 62nd round of the June 1988 draft. The 6-foot-3-inch prospect was the 1,390th player chosen in the draft, and Piazza recalls that his selection came with little fanfare. The Dodgers didn’t even contact him for several months after the draft. When they did, the eager major league hopeful requested a tryout and the Dodgers agreed.

In August 1988, Piazza was at Dodger Stadium crushing baseballs being served up by L.A. bullpen coach Mike Cresse. The balls were flying out of the stadium, Piazza says, thinking back on that fateful tryout. Lasorda and the Dodgers’ scouting director Ben Wade were looking on. Wade had his doubts about whether he wanted to sign a power-hitting first baseman, Piazza recalls. As the story goes, Lasorda said to Wade, “ ‘Would you be interested if a kid hit like that and was a catcher?’ And Wade said yes. So Tommy said, ‘He’s a catcher. Sign him.’ ” The transformation of Piazza from first baseman to catcher was underway.

“I had a strong arm. So before I left the tryout I threw some balls from behind home plate to second. I threw very hard that day. I think my arm still hurts from that day,” he says jokingly.

At that point, the Dodgers brass were convinced that he could be a solid backstop. Piazza was offered a $15,000 minor league contract and, he says, “I couldn’t grab the pen fast enough to sign it.”

The 19-year-old knew he had a lot of work to do if he was going to become a catcher in the majors, so he volunteered to go to a baseball training academy the Dodgers had in the Dominican Republic. For three months he started to learn the nuts and bolts of working behind the plate. His next assignment came in 1989 with the Dodgers’ Single-A Rookie team in Salem, Ore.

Piazza continued to work tirelessly and by 1991, he felt he was on the cusp of getting to the big leagues when he hit .277 with 29 home runs and 80 RBI for the Dodgers’ Single-A team in Bakersfield, Calif., in the California League. At age 23, Piazza was truly a Dodgers major league prospect when he started the 1992 season at the Double-A San Antonio (Texas) Missions. It took the young catcher only 31 games to impress Dodgers management enough to move him up to the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes, and by August he was wearing a Los Angeles Dodgers uniform.

Though he worked hard, Piazza fondly recalls his minor league days: “I think those moments, as much as they were difficult, were some of the more innocent times and just came down to having a lot of fun with the guys. Musketeers against the world. It’s the time when you cut your teeth. Go through struggles. I remember missing the ball and having to run to the backstop to get it and pitchers wondering, ‘Who is this guy catching?’ But with hard work I was able to get better and become a major league catcher. You go through those growing pains in the minors. There’s a bond because everyone is basically going through the same thing.

“As far as converting to a catcher, I think one of the things I was blessed with was so many great coaches along the way,” says the 16-year major league veteran (1992-2007). “I remember a great piece of advice that I tell young guys all the time: Listen to everybody. If they tell you 10 things and you find one thing that can help you, keep that.

“My first catching coach was with the Dodgers – Johnny Roseboro. Then there was Kevin Kennedy and Joe Ferguson. They helped me to progress quickly because they has so much experience.” Piazza even got help from Dodgers legend Roy Campanella.

��I enjoyed coming up with the Dodgers. I had an amazing career there. I got to know Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and all of the Dodger Hall of Famers and greats who stopped by and offered advice,” the 47-year-old Piazza points out.

The All-Star catcher also credits John Stearns and Jerry Grote, both of whom he met when he was traded to the Mets in 1998, for helping him continue to develop as a backstop. Both Stearns, who played for the Mets from 1975-84, and Grote, a Shea Stadium mainstay from 1966-77, played behind the plate and endeared themselves to the Mets faithful.

Piazza’s first full year in the major leagues was 1993, when he won the Dodgers’ full-time catching job in spring training and went on to capture the National League Rookie of the Year Award with a .318 batting average, 35 home runs and 112 RBI. He also got the chance to bask in the glory of a 62nd round draft choice excelling in the bigs.

“To me, my story just shows how great this sport is. You just need a chance. I was able to sneak into this game, kind of limp in, if you will. Through a lot of hard work and determination, some luck, some good timing, I was able to build a pretty good career. Baseball gives guys the opportunity to take many different paths to a good career,” the veteran backstop says.

Piazza’s manager when he first came up with the Dodgers in August 1992 was Lasorda, who couldn’t have been more thrilled to have Mike on the team. Lasorda remained Piazza’s manager through June 1996. The Hall of Fame manager, who was said to “bleed Dodger blue,” had to step down in the middle of the 1996 season due to illness.

Piazza rewarded the man who had such great faith in him by scorching the ball, never hitting below .318 or hitting less than 24 homers in a season while Lasorda managed him. In 1997, the Dodgers catcher hammered the ball with such precision he knocked out 40 home runs and posted a .362 batting average.

The Los Angeles Dodgers seemed to be totally enthralled by their catcher, now one of the elite players in the Senior Circuit. However, during the winter of 1997-98, a contract dispute arose, and the Dodgers and Piazza were still at odds when the 1998 season began. The inability to reach an agreement led to a trade that stunned the baseball world: On May 15, 1998, the Dodgers traded their All-Star catcher to the Florida Marlins.

Piazza recalls that almost immediately he started hearing rumors that the Marlins would not be his final destination. He was right. On May 22, the Marlins traded Piazza to the Mets, who were in serious need of a catcher. The whirlwind meant another transition for the backstop, who admitted that it “took some time” for the events of May 1998 to really sink in.

“I had no idea, I would end up with the Mets when the 1998 season started,” Piazza recalls. “For me, it was a tough time in New York at first. I wasn’t playing well by any means. Then I just decided to do the best I could. The fans responded. I ended up have an amazing experience in New York – eight amazing years. I’ve been rewarded and blessed by the support I received in New York. It’s funny. Sometimes in life, change is difficult and it’s tough. It knocks you out of your comfort zone. Sometimes, you just have to go along for the ride and make the best of it and good things happen.”

And they did for Piazza. He led the Mets to the postseason in both 1999 and 2000. In one 15-game consecutive stretch during the 2000 season, Piazza got at least one RBI in each of those games. That was the second-longest RBI streak in major league history. The Chicago Cubs’ Ray Grimes set the record in 1922, with 17 consecutive games with at least one RBI.

In 2000, the Mets went to the World Series, losing to the Yankees in five games, but Piazza had two home runs in the series. He also hit two home runs in the 2000 National League Championship Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, which the Mets won in five games.

But it was in 2001 that Piazza had “the moment.” It came on Sept. 21 and few New Yorkers will ever forget it. The Mets were playing the Atlanta Braves in the first sporting event held in New York City since the devastating events of 9/11. More than 41,000 nervous fans came out to the game, not knowing what to expect. There was a somberness in the crowd all night. With the score tied 1-1 in the top of the eighth, Brian Jordan of the Braves doubled to score Cory Aldridge from second. Aldridge was running for Julio Franco, who walked.

The Braves were leading 2-1 in the bottom of the eighth and an eerie hush fell over Shea Stadium. Steve Karsay, a Queens, N.Y., native came in to pitch for the Braves in the bottom of the eighth. Mets right fielder Matt Lawton led off by grounding out. Then Mets second baseman Edgardo Alfonzo walked. Piazza was up next and remembers that Karsay was just blazing the ball in.

The Mets catcher let the first pitch go by and it whizzed past him for a strike. He glared at Karsay and bore down. The next pitch came in even faster, Piazza says, but the now 33-year-old backstop was ready for it. He sent that fastball over the center-field wall and gave New York an emotional rush that may never be equaled. Piazza looked around and saw fans jumping, cheering, screaming, crying, “just about every emotion you can think of. I was able to do something for them.” The Hall of Fame catcher still gets a chill thinking about “the moment” and tears up.

Mets reliever Armando Benitez mowed down the Braves in the ninth and the Mets won a game they felt they just had to win. Piazza observes, “To be in the right place, at the right time and come through, it just comes from up above.” The slugger says 9/11 put his life in perspective and “made me focus on the important things in life, like family, friends and relationships.”

As meaningful as the home run was, Piazza shies away from the word “hero” in connection with that round-tripper: “No, I never considered myself a hero for hitting that home run, not even close. There were just too many others who gave so much more during that time, sacrificed and lost so much. I’m just happy if that homer gave people some hope.”

Piazza developed such a strong bond with New York and the fans there that he will have a Mets insignia on his cap on his Hall of Fame plaque. “The Mets fans were so gracious to me during my career in New York. Even in my post-career, every time I go back to New York, I can’t tell you how much the Mets fans embrace me. It’s very special. A relationship I can’t describe and it’s very emotional for me.”

After eight seasons with the Mets, the catcher became a free agent after the 2005 season and signed on with the San Diego Padres for 2006 before closing out his career with the Oakland A’s in 2007.

Considered one of the greatest offensive catchers to ever play the game, Piazza hit 396 of his 427 career home runs as a backstop. He hit the remaining 31 home runs as a first baseman or when he was in the game as a designated hitter. Piazza’s total of 396 home runs as a catcher is the most ever hit by a major league backstop. He had a lifetime .308 batting average and knocked in 1,335 runs. He also won 10 Silver Slugger Awards (1993-2002) and was named the Most Valuable Player in the 1996 All-Star Game.

In 1993, the Dodgers played in the Hall of Fame game in Cooperstown. After the game, Piazza purchased a ticket and went in to see the Hall of Fame. “I thought the only way I would get in was to pay,” he notes. Well, it took a little time, as things do for him, but Piazza did find another way into the Hall of Fame.

Robert Grayson is a freelance contributor to SCD. He can be reached at graydrew18@aol.com.