Features

The Hobby in the 1970s Part II With Jeff Escue

By George Vrechek

Editor’s note: The following is the second part of a two-part series on the collecting hobby of the 1970s with Jeff Escue. The first installment is HERE.

In the first part of this article, Jeff Escue described his experiences as a teenager in the 1970s going on hotel buying trips and selling at shows. This final part of the interview covers his collectors’ guide, buying, selling, autographs and other observations about the era.

Escue’s guide

Although Escue’s grammar and syntax had not developed as quickly as his nose for business, he decided to become a writer. He noticed that there wasn’t much useful written information about the hobby. He decided to fix that and make a few dollars from his expertise by publishing a guide to help beginners.

“I wrote a baseball card collectors’ guide. My brother printed the guide with a student discount, and it cost me 12 cents for each complete copy. I sold hundreds of copies for $2 or $3 through ads and card shows. I found three of the sale advertisements for the guide in old issues of SCD and The Trader Speaks from 1976. The guide I wrote in 1975 was my attempt at an enhanced but different version of Gar Miller’s guide, which I had purchased a few years before. Nothing else existed in the way of a collectors’ guide (that I was aware of) when I wrote the guide, and it was not easy to get information for most new collectors. My guide focused on the process of collecting rather than prices. The portion of the guide that discussed prices consisted of saying 1933 Goudeys sold for $2 and star cards sold for maybe double, etc.”

Upon re-reading his own guide, Escue observed, “My guide is a masterpiece of misspelling and poor sentence structure. If you could get an award for bad grammar, I would have had high honors.” However, his 20-page booklet touched on just about everything he had learned from the hobby, including mistakes that turned into learning experiences.

His ads for the guide included testimonials: Famous Chicago-area collector Rich Egan says, “Just what the hobby needs,” and nationally-known collector Don Schlaff says, “Every beginner should have a copy.”

“I had a few hundred copies left when I got out of the hobby and gave them to Roger Marth when he opened his card shop in New Lenox, and he sold or gave away the rest of them. Roger is a good guy. I saw Roger a few years ago. We remembered his first forays into the hobby, including relaying the story of his childhood collection having glued some ’52 Topps, as I recall, to his wall in his house. That is what happened to cards before the hobby emerged.”

DiMaggio’s autograph, but the wrong DiMaggio?

“The cover had an autographed 1939 Play Ball Joe DiMaggio card. Some 20 years later, Dave Mediema mentioned in an SCD article that someone sold a guide which featured a fake autograph of DiMaggio on the cover. That must have been me! Dave was a good guy, and if he recalled it was my guide, he probably would not have mentioned it. I got the card from someone who had sent it to DiMaggio. Likely it was DiMaggio’s sister who signed it.”

Other guides

Bert Sugar first published The Sport Collectors Bible in 1975, and it included descriptions and some pricing, but Escue was not aware of it, nor had he seen Jefferson Burdick’s American Card Catalog. Escue felt that the hobby’s use of Burdick’s nomenclature of T, E and R categories to describe sets created a bit of mystery and confusion with the many new collectors entering the hobby.

Several other collectors or dealers made attempts at price guides as well as hobby publications during this period. Without the Internet around, there was a virtual explosion of pulp in the 1970s. SCD started in 1973, TTS in 1968. The average age of the four major hobby publishers in 1975 was 31 years old.

“Jim Beckett so wisely provided the hobby a few years later with great guides which were focused on individual card pricing,” said Escue. “Jim’s intelligent and honest approach to the hobby allowed collectors buying his early guides to have confidence in the information. Jim’s guides took the hobby to another whole level.”

Card show deals

“To a large degree in the early 1970s, it was not socially acceptable for anyone over the age of 13 to collect cards, at least where I lived. Adults collecting baseball cards carried a very strong negative stigma. You had to keep your mouth shut, or you were thought of as very strange, collecting children’s stuff. By the mid-’70s, card collecting became much more socially acceptable.

“At some shows I had my greatest success, because I was 15, and people off the street, possibly with a bit of larceny in their hearts, sold to the youngest guy in the room figuring they were getting rid of old, fairly worthless stuff to a dummy. Big mistake. By the time I did shows, I knew more about card values than most of the sellers in the room, thanks to picking Keasler’s and Steinbach’s brains.”

A nice box

“One guy had a box of about 700 1936-41 era cards and premiums and a box of magazines from the same era. He wisely walked around the show. He noticed hardly anyone had any magazines for sale, especially from that era, yet probably 20 percent of the tables had cards like he had, so he erroneously concluded the mags were the gold . . . oops. He wanted $200 for the cards and that’s what I paid. This was the biggest find, likely ever, of the R314 cream colored Canadian style premiums (Type 4). I had at least three sets, and most major advanced collectors only had at best a few of these cards. This set had DiMaggio, Feller, Hubbell, Greenberg, Appling, Averill, Doerr and Gehringer. These were extremely popular with advanced collectors.

“Also the box included lots of ’39 and ’40 Play Ball high numbers, all VG to MT. Years later Roger Marth bought my ’39 set. From that same box I sold a ’41 set at a later show for $200 after failing to get $225 for it at a major convention. There was no money available at these shows relative to what cash was in the hobby only 10 years later. A Mint 1952 Topps set was auctioned for $950 at one show. Chicago had only one show a year the first year I was involved, and it then went to two shows a year, not two major shows, two shows period.

“I would bring home $1,000 extra cash from sales and more cards than I started with at most shows I attended. I was very good at buying stuff that walked in off the street. I was also very good at trading and obtained more value and cards than when I started a trade.”

Walk-ins

“I picked up some great buys from people walking into shows with a box of cards, and I would call over to my table anyone carrying anything, bag, box, etc., that might be cards – paper sacks were a common container. Some shows started getting complaints that the show organizers were poaching everything at the front admission desk, so they started directing all walk-ins to auction their cards to appease the sellers setting up.

“I also would watch for people walking around who were only looking at cards, not buying. I guessed they might have cards to sell and were trying to understand pricing. I collared them as they walked past my table and asked if they had anything for sale. This worked very well, and I never saw anyone else doing this.

“In Cincy, for instance, a guy said, ‘Yes, I have a box of cards in my car.’ He wanted to finish looking over what sellers were selling similar cards for, then he would stop back and let me see what cards he had and let me know what he wanted for them. Besides 1950s Topps and Bowmans, he had a near set of Dan Dee Potato Chip cards including Smith and Cooper, the two rare ones. So yes, it paid to be innovative and observant.

“When buying cards, if the seller would not set the price and forced me to make an offer, I would add up the value of the superstar cards and pay that price. The commons were free and represented the future profits before other expenses. Invariably the commons, with their vastly greater quantity, were worth about the same total amount as the superstars at that point in time. That gives you some perspective of the relationship of values of star cards to commons. In other words, I would offer 50 cents on the dollar. You would do fine buying that way and that is how many people assessed how much to pay for purchased collections. Using this method I do not remember ever being surprised, either up or down in value later with what I got. This was a shortcut for when you did not have time to dawdle at a show or during a hotel buying trip. You just had to get it done and move on, hoping something else would walk through the door five minutes later.”

Advertising results

“I simultaneously advertised in the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times that I wanted to buy pre-’58 baseball cards – almost no response. I spent about $100 in ads, then finally got one lady from Michigan who had a near set of ’53 Topps which she wanted $30 for. I happily paid that and when the cards arrived she had included maybe 15 or 20 Dixie Cup lids, which were very in demand at that time.

“I had a guy from Aurora call me with 1,000 ’50-’53 Bowmans. He wanted a penny each, but they were a bit damp at one time and very musty smelling he said. Since I would have to drive 30 miles and pay a penny each and did not know how bad the cards really were, I passed.”

Floating the cards

“If you got cards that were glued into a scrapbook, not that uncommon for 1930s-era cards for some reason, you would toss the pages of cards in a sink or bathtub and soak them. They usually were glued with something like Elmer’s glue, which would come loose with very little soaking and often little or no damage. You just had to press the cards to keep them flat as they dried.”

Memories versus reality

“A friend moved in 1970 and gave me about 1,500 cards from ’65-’70. Many years later he evidently gets on eBay and sees a ’68 PSA 10 common sell for $500 and a PSA 9 Nolan Ryan sell for big bucks, and, of course, he is sure that is exactly what he gave me. Not a chance. But everyone thinks they had gem perfect 10s. In hindsight, he is sure his cards, which were worth about $25 when he gave them to me in 1970, were worth a fortune (years later).

“I see that I auctioned these along with my childhood card collection in the 6/75 The Trader Speaks issue. I probably got $90 for his and my childhood collection. The reality is virtually every kid handled and played with their cards, like they are supposed to. Most cards like mine and my friend’s would be graded PSA 3-6 at best today. We kept them in rubber band stacks. Yikes!

“Since, for the most part, I dropped out of the hobby in 1977, my memories from that era are not tainted with many of the gradual changes that occurred and registered in people’s brains who were constantly in the hobby from say 1970 onward. Very few people walked away from the hobby just before the hobby really took off. I run into some of the collectors from that era and they mix the ’80s and ’90s with the ’70s memories since they never left the hobby. Their brain blurs the lines of reality, not intentionally but as a normal occurrence.”

Beckett saw the stars

“Jim Beckett was a nice guy and very bright. He was a statistics professor and probably thought about the hobby in those terms. But what he got from that era, that most everyone missed, was the popular players, i.e. Mantle, Mays, Aaron, etc., would be the truly great cards in the future, much more so than the commons. He really understood the future in terms of psychology of the masses wanting to identify with the heroes of their past, not the commons, so to speak.

“He explained this to me to some degree, but I was focused on the fact that for the most part as many Mantle cards were printed as Horace Clark, so why would Mickey’s late ’60s cards be worth way more than a common Horace Clark? As a result, I did hear what he said, we all saw the demand for star cards from the masses at the shows, especially from new collectors, but it never really sank in with me at the time. Lots of people observed the star card phenomenon, but we had no idea how much it would steamroll. Once again, I focused on supply, not demand. Jim understood demand. This is so obvious now, but not as many people understood this back then, as Jim did.”

Others in the hobby

“Mike Cramer, our wives and I had a very nice visit at Mike’s house a few years back. He was a really bright guy and one of the few who treated me really nice back in the 1970s. Mike worked the Alaska fishing boats back in the 1970s – very dangerous and demanding, and a very high-paying job. Mike put that money into cards and eventually launched the Pacific Trading Card Co. to print licensed sports card sets.

“Cramer bought a ton of retailer or wholesaler returns of Topps cards and warehoused them for a few years before selling them into the hobby – same thing Larry Fritsch did. Not many people stockpiled the current stuff. This was before stores, and only a few people had mail-order businesses.

“People I remember from the Chicago, Cincy and Indy shows were Ed Nassiff, Dick Ruess, Orlando Iten, John Stirling, George Husby, Jack Urban, Dick Millerd, Rich Binder and Tom Koppa.” Sellers would bring regionals from their areas.

Regionals and premiums

“Most of us correctly observed that regionals, i.e. Wilson Franks, Rodeo Meats, Glendale Meats, etc., were exponentially rarer than the Topps and Bowman sets. Likewise the Goudey premiums were massively rarer than the Goudey cards. Many of the advanced collectors were happy to put their money in regionals and premiums, which are largely forgotten today relative to the main Topps, Goudey and T206 sets.”

“Recent” commons and what to hang onto

“Keasler told me (in 1973) not to mess with ’65 Topps and forward since they made so many of them relative to how many collectors there were. Here again, look at the lesson Mike learned from all of his buying adventures. He would not even buy them unless something else came with them. They told the people to keep them, maybe they would be collectible later.

“This was very logical, if you had come from the prior 20 or so years in the hobby with such slow growth. He saw the volume of cards available because of hotel buying trips and made a reasonable assumption the demand would continue as it had in the ’60s, very slow. Instead the increased volume of cards and exposure of the hobby to the general public that resulted from these hotel buying trips actually massively increased the demand and quickly expanded the number of collectors. By focusing on the experience of the prior 20 years, many major collectors totally missed what was about to happen. We understood supply and did not anticipate the soon to be explosive demand.

“Bottom line, if I had kept anything, it would have been the Goudey premiums, regionals and a few other sets based on incorrect ideas relative to current values as I see on eBay. Also I might have put the cards I kept into the early plastic pages. Besides dinging the corners as I slid them in, I would have woke up 10 years later to find the oil had leached from the early plastic pages and been mighty ticked off. So, I am glad I sold out back then.”

Condition

“Keasler was very keen on condition and would sit with each new card that he got, (if it was in obviously great condition), and compare it to his existing sets to upgrade, and he had awesome stuff. Keasler sold some of his stuff to Alan Rosen. He was the only true condition freak I saw. I never knew anyone who looked at gloss or printer marks except Mike back in the 1974 era.

“Jim Beckett was also very cognizant of condition, but I never saw his collection. Others looked to improve their cards, but it was not an all-encompassing activity like it is today.”

Selling by mail order

“To understand how little importance was given to condition in the mid-’70s compared to today, my April 1976 SCD ad mentions – ‘I have at least two of each lot.’ It was very common to wait to sell through the hobby publications until you had multiples of the same items. If I had three DiMaggios from the R314 cream colored Canadian Goudey Wide Pen Premium set (which I did), and they were VG, VG/EX and EX, respectively, I would list the card as VG in the auction. That way, if I got seven bids I would usually fill the top three bids giving the EX condition card to the highest bidder. This is because the advertisement cost was more than the monetary difference we could receive from focusing on the different condition of the card in many cases. In 1976, TTS was $40 for a full page ad ($167 in today’s dollars) and $11.50 for a quarter page. Selling this way was common from my experience talking with other sellers.

“When you won an auction, you were notified by mail: here is what you won, send me this amount. The whole process took about three months from the time you hand-typed your ad, mailed it in and the ad showed up the next issue, which was monthly. Then you waited about two weeks after the ad ran to make sure all bids showed up, notified the winners, many were very slow paying because they did not have the money to pay (no exaggeration), then you mailed them the cards first class mail in an envelope with minor cardboard. This further emphasizes that condition was not that important, getting the missing number to complete your set was what was important.

“Long-distance calling was quite expensive relative to the value of the cards. I remember visiting my grandmother, who was very old school, and taking along a copy of TTS to read. I saw a guy had some Rodeo Meats that I wanted, and he listed a phone number out of state. I called the guy four or five times and his wife always answered; he was never home. He would not return a long-distance call. Finally I had to give up. My grandmother yelled at me for quite a while running up her phone bill to the tune of like $4 for those calls.”

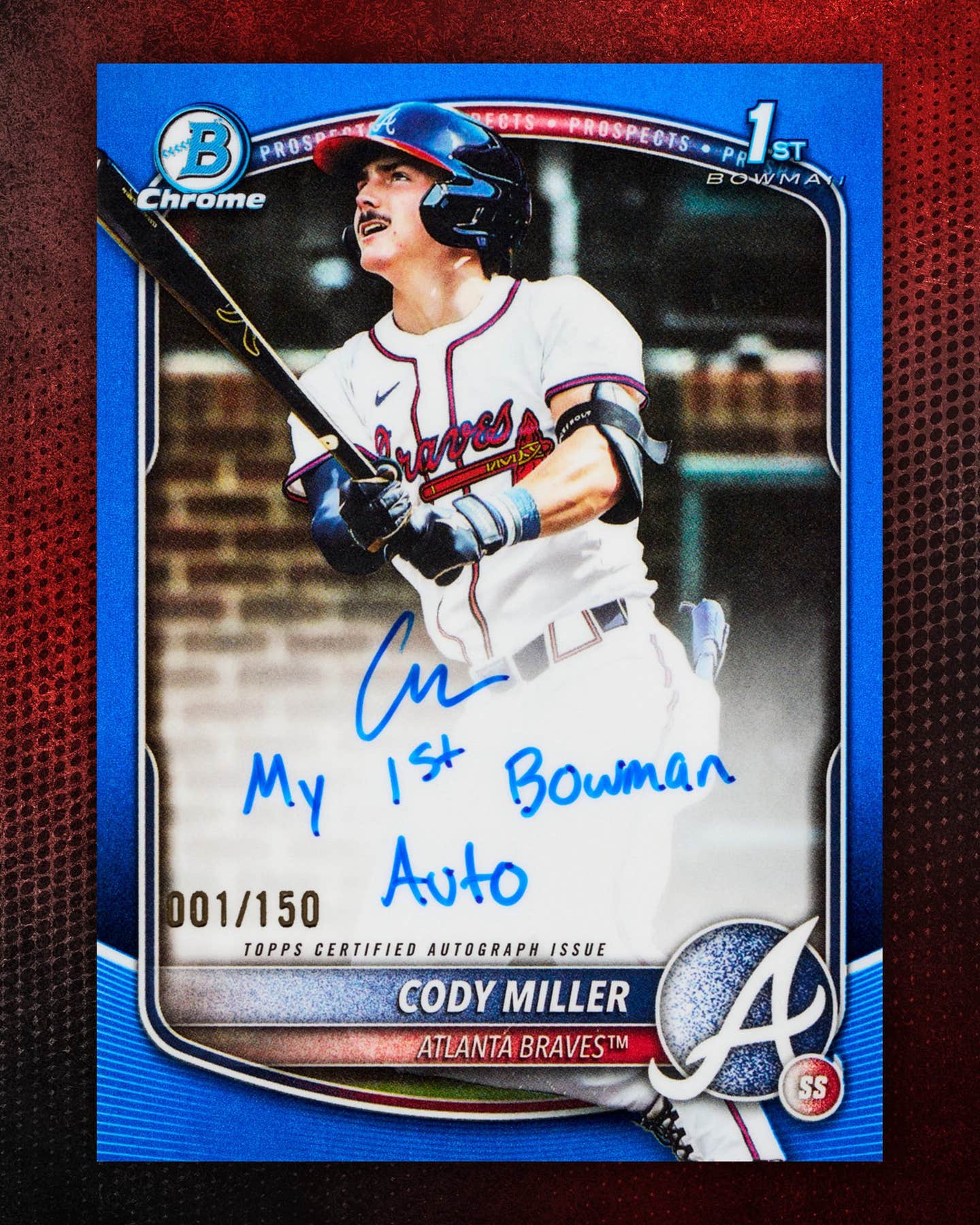

Autographs

Escue remembered: “Autographs were another thing that is different today. Many advanced collectors bought Jack Smalling’s address guide. The list had thousands of former players’ addresses. Steinbach and Keasler had areas in their houses set aside to send out autographs, a little work station so to speak, and would work in their spare time to write a request, stamp envelopes and SASE, and send out hundreds of requests each month. Often the card was sent with two 3-by-5 index cards to act as stiffeners to help avoid card damage and get two more autographs on the index cards. This highlights once again how condition was not that big a deal.

“Who would send out a Mint 25-year old star rookie card now to a player, even if they would sign for free? The main focus then for autographs was HOF and former players from the ’20s-’50s. I sent off a color pic of Lefty Gomez and got that autographed, but that was about it. This is one of the few things I kept.

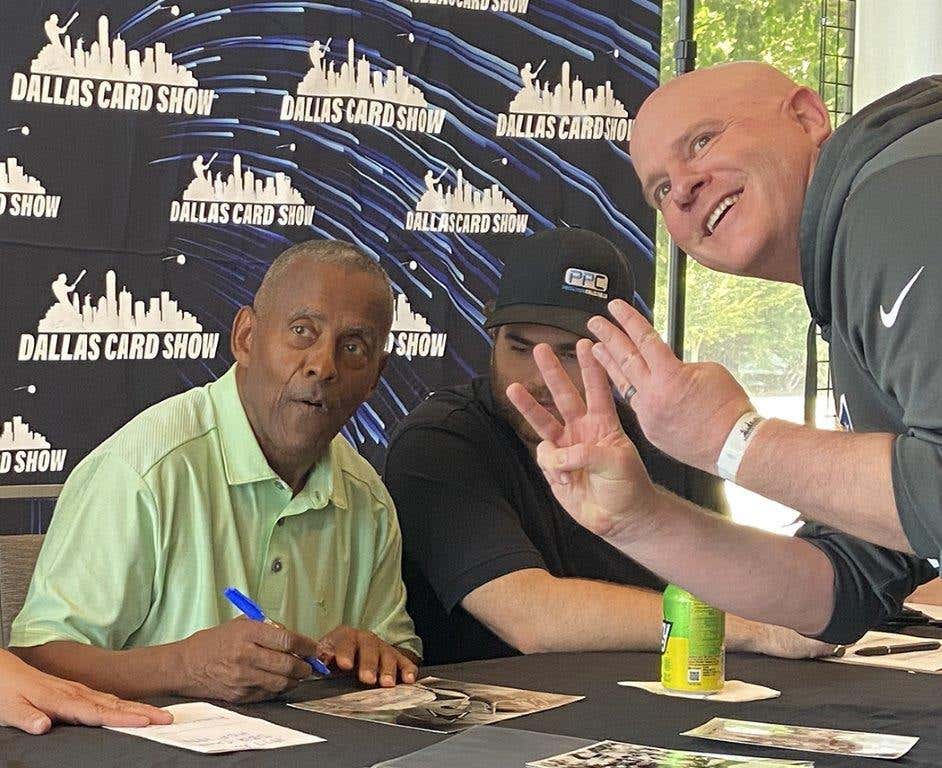

“Years later, I met Mickey Mantle at a show in Illinois and got a baseball autographed, shook hands and got a picture with him. I remember at one of the early 1970s Chicago shows they had Bob Feller as a guest signer. What a concept, a genuine all-time great signing autographs at a card show. I recall the show promoters paid Bob a flat fee. Then Bob signed for collectors for free. The media ate it up. That is obvious and common now, but once again this was groundbreaking in the early ’70s.

“I had a 1933 baseball players’ guide book with a hard cover. It had most of the major league players. Inside it had a great picture of the player, his stats and, most amazing, it showed the player’s current home address. Think about that for a minute, Lou Gehrig’s home address (and everyone else’s) in a guide book that you could have bought at a book store in 1933.”

College fund

“For a while I rolled my baseball card profits back into more cards, so when I finished a set I held onto the set for a short while. I read the backs and held the cards and got a kick out of the history. Then I sold the set and chased another set, always churning. When I entered college, I sold everything to pay for college. When I grew up we did not know a single adult who had ever gone to college except for our school teachers and physicians. College was an exotic concept where I came from.

“My buying adventures resulted in my acquiring lots of 1933-41 and 1952-61 cards, which are all gone now, but it was sure fun to have owned at one time. It would be nice to have focused on being a collector exclusively and to have kept the cards, however, I did not have the luxury of keeping my capital tied up in a hobby. Selling the cards was a way to move forward. I got to own some great cards and sets and that is more than most people had the opportunity to do.”

While Escue may not have sold out anywhere near the peak, his timing was fortunate. A few years later his parents’ home flooded. The basement where he would have kept his cards took on 5 feet of water. Escue had cashed in on all his cards before the flood.

Looking back

Escue concluded, “The McDonald’s football cards lured me back into the hobby briefly in the late 1980s, but my early-and-mid-1970s experience remains ‘frozen in time’ and brings back many fond memories. The lessons I learned in the ’70s about supply and demand, marketing and general business served me well later in life, as I was fortunate to have a very successful career in business and now am focused on gaining spiritual wisdom. Life is good.”

Escue is happy to now own just some reprint sets of the vintage cards he once had. He can read them and not worry about bending them. Every so often he’ll drop in at a show or pick up and read an auction catalog to stay in touch with the hobby that he enjoyed. It is often the players he enjoys recalling rather than the cards themselves.

Jeff and his wife retired a few years ago and moved to the Northwest. If you are an old acquaintance and would like to share memories, or if you have copies of his old ads in your back issues of SCD and TTS, he can be contacted at jsq2@yahoo.com.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to Sports Collectors Digest and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.