Featured

Book Review: ‘The Cracker Jack Collection’

By John McMurray

Considering the dearth of quality books focused on vintage baseball cards, The Cracker Jack Collection: Baseball’s Prized Players (Peter E. Randall Publisher, 2013) by Tom Zappala and Ellen Zappala with John Molori and Jim Davis is a welcome addition to the collecting field.

Not only does this 177-page book provide high-quality, full-color presentations of every card in the 1914 and 1915 Cracker Jack sets, but it also complements these cards with a sense of context, discussing the roots of the product’s inclusion with Cracker Jack candy, as well as the differences between the two issues.

In keeping with the style employed by the authors in their earlier book, The T206 Collection: The Players & Their Stories, the centerpiece of this book is the individual player biographies. Each player receives a roughly 500-word sketch that appears in conjunction with his respective Cracker Jack card. While much of each biography focuses on a given player’s statistical achievements, there are also many complementary off-the-field facts, including, for instance, that Joe Bush was a ventriloquist, that Al Demaree became a noted sports cartoonist and that Hans Lobert reportedly once raced a horse.

The book attempts to strike a balance between serving as a detailed work of history and also being lighthearted. Though each entry includes the player’s major on-field accomplishments and statistics, many of the player biographies begin with reflections about a given player’s nickname and conclude with a witty remark. About a quarter of Rabbit Maranville’s bio, for one, discusses the origin of his nickname, while ending with the line: “This Rabbit surely enjoyed a 24-‘carrot’ gold career” (p. 55).

Similarly, the roots of Solly Hofman’s “Circus Solly” nickname are discussed at the beginning of his entry, which concludes with the sentence: “All in all, between his hitting, fielding and base stealing, ‘Circus Solly’ Hoffman was no clown” (p. 78).

Since the player biographies are written in a particularly clear and engaging style, they are accessible to both fans and non-fans alike. Moreover, obscure players like Hal Janvrin and Possum Whitted are treated with the same level of rigor as are the established stars of the period, giving the book a sense of balance.

Because the player biographies oscillate so frequently between statistical precision and whimsical reflection, however, they often lack the gravitas that one would find in a more traditional presentation of baseball history. Some of the authors’ wording relating to players’ deaths underscores that impression. In Frank “Wildfire” Schulte’s bio, for one, the authors conclude by saying, “Three days before the World Series in 1949 Wildfire Schulte’s flame went out permanently” (p. 88). Similarly, Bob “The London Flash” Bescher’s death was noted in this fashion: “Tragically, ‘The London Flash’ lost his life in a flash when his car was hit head-on by an oncoming train in 1942” (p. 69). In reference to Clyde Milan dying of a heart attack, the authors say: “‘Milan the Marvel’ was robbed of life as quickly as he robbed those bases” (p. 83).

The concern is not that the authors interject humor or wit into their critiques from time to time, but instead that its overuse can take away from otherwise well-presented work.

In Chapter 2, the authors present their Cracker Jack All-Star team, namely their own selections of the best players by position included in the two Cracker Jack sets. While most choices are beyond reasonable dispute (such as Honus Wagner at shortstop or Ty Cobb in the outfield), the selection of Jake Daubert at first base over Frank Chance and of Eddie Collins at second base over Napoleon Lajoie will surely inspire debate, which the authors say they invite.

An additional consideration is that some of the language which the authors employ occasionally borders on overstatement. Former Detroit Tigers outfielder Sam Crawford is described in the book as being “one of the founding fathers of our National Pastime,” a bold claim most likely based on Crawford being active at the time the American League was formed and on his longtime role as an influential college baseball coach (p. 75). Clark Griffith, though accomplished both as a player-manager for and later owner of the Washington Senators, surely could never live up to the authors’ assertion that he “would be as influential in Washington as any U.S. president” (p. 155).

Further, when referring to Detroit shortstop Donie Bush, whom the authors say was “the epitome of a Major League ballplayer,” the authors contend that “whether it was a walk, sacrifice, or a key hit, Donie Bush always delivered,” a lofty claim for a career .250 hitter (p. 52). While Sherry Magee of the Philadelphia Athletics surely was productive over a long period of time, the authors’ claim that Magee was “the prototypical five-tool player” is an overreach (p. 81).

In fairness, the authors do not sugarcoat the accomplishments of lesser-known players, including reference to the “very vanilla career” of Herbie Moran (p. 85) or mentioning that “George Baumgardner would be classified as a common” (p. 115). In describing Eddie Cicotte, banned from baseball as part of the 1919 Black Sox scandal, the authors conclude: “Ultimately, Cicotte’s legacy of awesome pitching is forever tarnished by awful decision-making” (p. 125). The authors also take a measured approach in making claims for the Hall of Fame candidacies of Stuffy McInnis, Jake Daubert and Bobby Veach.

A vexing aspect of the book is that no sources are cited. Even though The Cracker Jack Collection is a coffee table book and not intended to be primary source history, the biographies would gain in authority if the authors informed readers of the secondary sources on which they rely. Further, while basic statistics and matters of fact are in the public domain, it is hard to assess the reliability of many anecdotes without knowing from where they derive; a cited work would allow readers to seek further details on particular anecdotes, like the one discussing Bert Niehoff’s decision in 1931 as manager of the minor league Chattanooga Lookouts to bring in a female relief pitcher, who went on to strike out both Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth (p. 45).

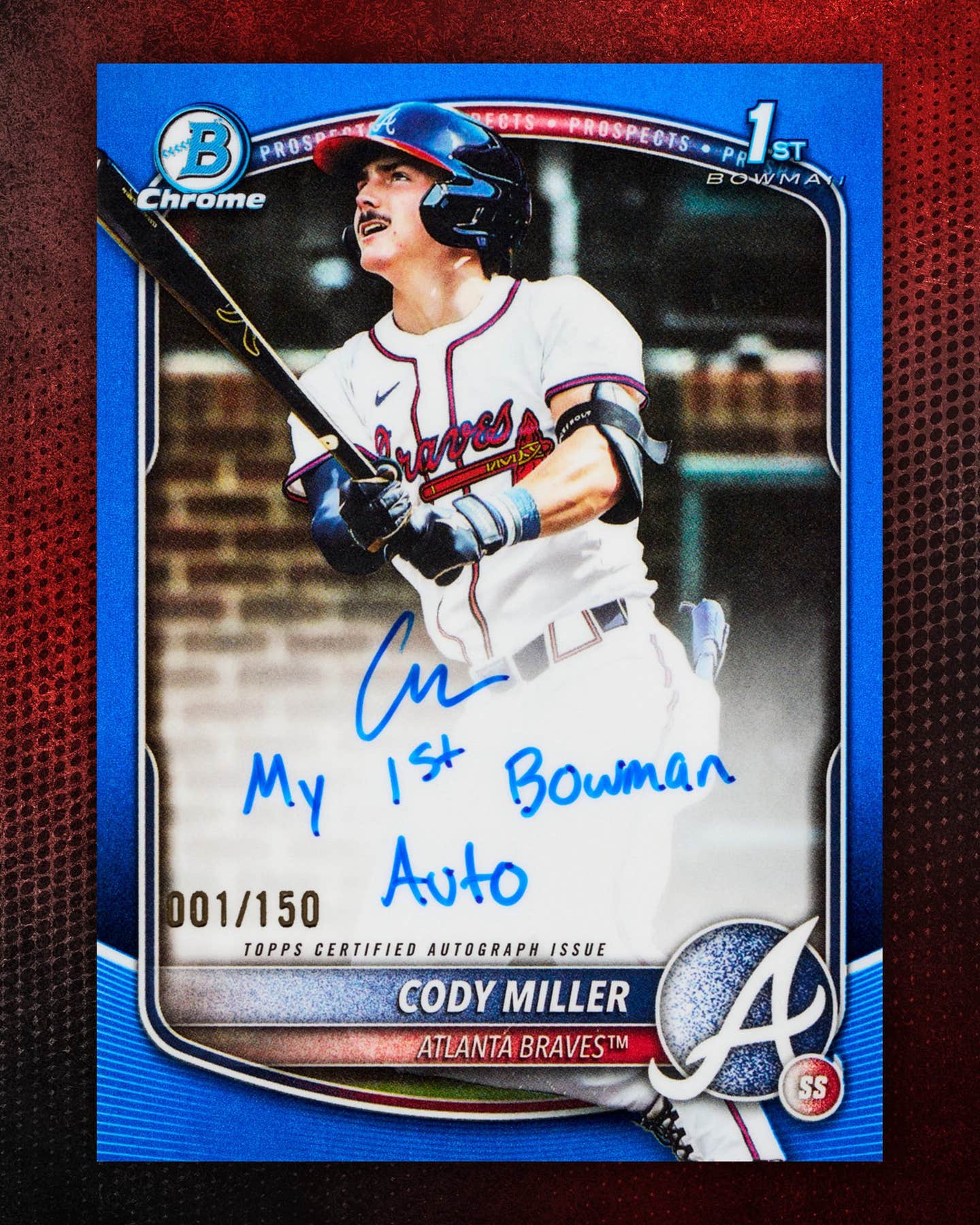

The overall visual presentation of the book is excellent. The cards shown in the text, which were provided by Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA), are high-end examples that are sharp and inviting. At the same time, the included photos typically maintain the look and feel of vintage baseball cards, most notably the difficult-to-find 1914 Christy Mathewson card. Pictures of vintage Cracker Jack advertisements and baseball equipment also appear in the book and give it a wonderful contemporary feel. The colorful cards printed on shiny paper make this coffee-table book an excellent display piece.

Though surely no book is without flaws, there are a few notable errors worthy of correction. In Bobby Veach’s biography, the authors remark that Veach was “the only player to ever to pinch-hit for Babe Ruth” (p. 90), when, in fact, several position players pinch-hit for Ruth while he was a pitcher for Boston, and outfielder Ben Paschal pinch-hit for Ruth with the New York Yankees two years after Veach did so in 1925. On page 151, the authors also claim that Joe Wood – who died in 1985 – was the last surviving player from the Deadball Era, even though Chet Hoff, who made his major league debut in the middle of the Deadball Era in 1911, lived until 1998. Less substantively, the authors clearly meant Albert Pujols when they referred to ‘Alex’ Pujols (p. 25).

The authors provide an extensive presentation of the development of the Cracker Jack confection and describe how the cards came to be included as a prize. They note that since the 1915 Cracker Jack set could be obtained via a mail-in promotion, there are more existing cards from that edition in top shape than from the 1914 set, which could only be obtained by purchasing the product.

In the Foreword, Joe Orlando, president of PSA, says that the Cracker Jack set is “one of the most eye-appealing releases ever manufactured” and contains “some of the best visuals ever captured on cardboard” (p. IX), two assertions that would likely be affirmed by most collectors. The authors also make the more debatable claim that the Cracker Jack cards should hold an elite place in the hobby on account of their unique appearance and because of their connection with the candy, noting “what takes the issue to another level of importance is the cultural link to the game itself as a result of the set’s affiliation with the Cracker Jack confection” (p. 173).

The book would be more complete if the authors had included images of the backs of the cards, which set a new contemporary standard for detail. While the authors frequently comment on the aesthetics of the fronts of the Cracker Jack cards, the text of the backs is never considered (except for the note in the Introduction that “There is some information [relating to the individual player narratives] on the back of the original Cracker Jack cards, but not a heck of a lot” (p. XII)).

Although the omission of the card backs might be because the text on the reverse of the cards frequently amounts to a list of a particular player’s milestones and accomplishments (a representative example: “George T. Stovall, manager of the Kansas City Federal League team, was born at Leeds, Mo., Nov. 20, 1881. He was a member of five different minor league clubs in 1903. He signed with the Burlington, Iowa State League Club in 1904…”), it is nevertheless surprising that the book does not include a single image of a Cracker Jack card back.

One of the most instructive parts of the book is the final chapter, which outlines the similarities and differences between the 1914 and 1915 Cracker Jack sets.

Considerations such as whether the text on the reverse was right-side-up (as it was in 1914) or upside down (as it was in 1915) and the thickness of the paper used in each set are cited as distinguishing factors. The authors also note that while there are 32 more cards in the 1915 set, only four players (Harry Lord, Jay Cashion, Nixey Callahan and Frank Chance) appear in the 1914 set but not in the 1915 set. The frequently overlooked contemporary poster advertising the Cracker Jack cards, which the authors include on page 167, is particularly interesting. This chapter likely provides the most comprehensive and nuanced comparison of the two sets that is available anywhere.

The Cracker Jack Collection should be commended for what it is: An effort to bring attention to a classic vintage card set. The book does so with a striking visual display. Opportunities remain to go further in a subsequent edition or book, perhaps with more elaborate biographies and with an examination of the card backs. For an introduction to the set and an engaging set of player biographies, The Cracker Jack Collection fills a gap in the hobby’s literature.

John McMurray writes a monthly column for SCD. He is chair of the Deadball Era Committee of the Society for American Baseball Research, which examines and chronicles baseball history from 1901-19, and has contributed player biographies to SABR’s BioProject. He can be reached at jmcmurray04@yahoo.com.