Features

In-Depth Look at 1953 Topps Pt. 2: The Final Print Run

By George Vrechek

In the recent previous half of this article (Dec. 25, 2015, issue of SCD), we explored the print layout of the 1953 Topps Baseball set through the third print run. We pick up the story with the final print run and look at what all this may mean.

Final printing gets complicated

The final print run of most Topps sets had the lowest sales and, consequently, has the highest prices today. Topps was ready to go in the final run with 28 more National Leaguers and 32 more American Leaguers, which would have evened out the leagues in the entire set. It would make sense to match two rows with the same colored bases to form strips of 20 cards. With the 20-card strips needing to remain together, the logical layout would have been two sheets with 40 players printed three times and 20 players printed four times. However, there weren’t 60 players in the final printing, but only 54. The story has been around for a long time that Topps withdrew six cards because of questions about the strength of the Topps license agreements.

In 2014, Bob Lemke reported the find of an internal Topps memo confirming the identity of the missing six players. Keith Olbermann reported Lemke’s find on ESPN. The missing players are Joe Tipton, Ken Wood, Hoot Evers, Harry Brecheen, Billy Cox and Pete Castiglione. The missing numbers are 253, 261, 267, 268, 271 and 275. The artwork was also found. Blogger Bob Wong even prepared a layout for the cards. (See http://bobscustomcards.blogspot.com/search?q=1953+topps.) The 54 cards printed by Topps were missing four (red) American Leaguers and two (black) National Leaguers to keep the ink from bleeding. The six players listed in the memo would have filled the voids exactly.

Bowman didn’t use Brecheen and Castiglione either in 1953; the others were in the 1953 Bowman sets. The six players may have been originally intended to be in earlier print runs, which would be more logical than having all of the licensing problems in one batch. Maybe they were problem children as early as the first print run (with the five out-of-sequence numbers), got pushed off to the last printing and then finally dropped. There was also artwork for Ashburn, Simmons, Pafko, Lanier and Suchecki that never made it as far as the list of 280.

Step 1 – the solitaire game

I used mock-ups of the six missing players, along with the 54 cards that were issued to play my game of 1953 Topps solitaire whereby I matched red and black bases. The price guides began identifying short prints and DPs in this final series by the late 1980s. The colors and box locations matched nicely except cards known as short prints and DPs in the price guides didn’t exactly match the normal base-color layout.

I played with the cards and moved a minimal number of players between the short print and DP rows. I took into account miscuts we found involving Mays/Sandlock, Sandlock/Hudson, Coleman/Bolling, Woodling/Pillette, Roe/Haddix and Krsnich/Milliken. In most cases the miscuts were very slight and the resulting clues very obscure.

Step 2 – pull six cards

The next step at Topps was when Berger probably ran in to stop the production of the six cards with licensing issues. Six cards were pulled. But what happened to fill the holes created in the layout? Other cards from that run had to be used which would have meant that six other cards would have been printed more times than usual. Logically those re-used cards would have been the same color and justification as the pulled cards.

Step 3 – replacements and finally back to Sid Hudson

Unlike any other 1953 Topps cards I have seen, the red-based Sid Hudson was printed next to a black-based card (see Part 1 of this series). Logic would say that at least one other red card would have been tainted by the intruding additional black card. It didn’t take too long to find miscuts that lead Billing and me to the conclusion that two of the cards butting up to Hudson were the red Bob Oldis and the black Mike Sandlock. Oldis miscuts seem to consistently have a black border courtesy of Mike Sandlock. Hudson and Oldis weren’t the oddballs; it was Sandlock. National Leaguer Mike Sandlock, who is still with us at age 100, got copied from his spot next to Willie Mays (determined from another miscut) to a space next to Sid Hudson, which had been reserved for one of the pulled American Leaguers. Finding Sandlock on the sheet in two different places also adds credibility to the position that Topps never printed and destroyed cards for the missing six players, but just substituted other cards in the same run like Sandlock.

We have not found any other instance of a card being matched like this. Why did the black-based Sandlock get moved instead of a red card? Maybe the Topps art department had to go to lunch, and Sandlock got the nod. We don’t know. Nor do we know with certainty the identity of all six cards that filled the voids created by the pulled cards. Absent any other miscuts with a trace of the wrong color, I would have to assume that the other replacement cards matched up.

Depending on what row the replacement cards were pulled from, they could have been printed either six, seven or eight times on the two 100-card sheets comprising the fourth run. Based on miscuts, it looks to me that Sandlock, Joe Coleman, Preacher Roe and Gene Woodling were four of the “high-multiple” prints.

I took a stab at guessing the identities of the other two cards as described later. The six replacement players likely also remained in the same row that they were in originally.

Team totals

Again the player totals by team are unusual. In the final printing there were nine Pirates (who had the worst record in MLB), six Reds and six Dodgers. There was only one Indian and there were no Cubs, Braves or Phillies. For the entire set, 17 cards per team would have been average. There were only nine Phillies, but 23 Cardinals, 21 Dodgers and 21 Yankees. Did licenses for the Phillies get sewn up by Bowman of Philadelphia?

Miscuts and uncut sheets, where are you?

I was able to find a few more miscuts, which added reality to my hypothetical sheet layout exercises. Unfortunately, Topps quality control in 1953 wasn’t too bad, and there doesn’t seem to be a lot of horrible miscuts around or partial sheets that were retrieved from dumpsters. I confirmed with dealers Al Rosen, Kevin Savage and Dick DeCourcy that they have not seen any new uncut 1953 Topps sheets or partial sheets. A search at the last National for 1953 miscuts came up empty as well, although dealers don’t usually tout their miscuts.

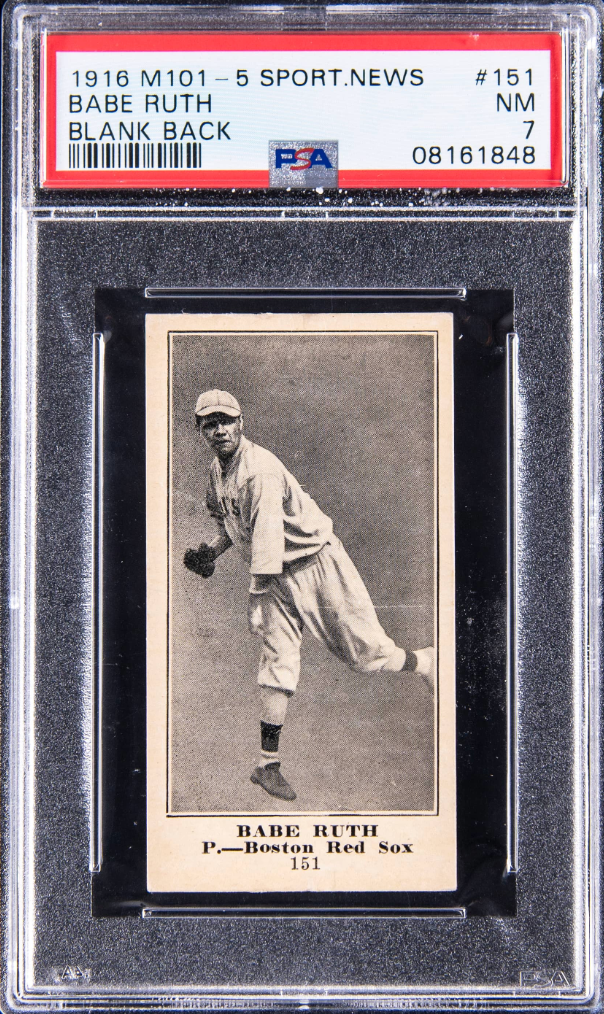

PSA populations

What we do have, however, are population numbers published by PSA for each of the cards they have graded. That should give us some clues about print quantities.

PSA has graded more than 118,000 1953 Topps. If everyone had sent their cards in to PSA to be graded in 1953, we wouldn’t need any uncut sheets to figure out the print runs. The PSA population numbers would tell us everything we need to know. However, in 1953 no one had thought about putting baseball cards in plastic cases before flipping them or trying to stick them in bike spokes. Consequently, only the survivors in fairly decent shape or star cards have made it to PSA. For example, the PSA population reports show that 92 percent of the 1953 cards were graded VG-EX or better. Six players (Campanella, Mantle, Jackie Robinson, Page, Mays, Ford and Berra) make up 3 percent of the set but account for 10 percent of the grades.

First, throw out the super stars

To test the relationship among the PSA population numbers, I set aside the frequently graded star cards as not being representative of relative scarcities. I then divided the commons by print run and identified cards as being either SP or DP according to the price guides for print runs 1, 2 and 4. (Print run 3 has not been divided between SP and DP in the price guides.) I then compared the number of cards graded by print run and whether they were listed as SP or DP. I found quite a range of numbers, indicating some scarcities but not nearly the scarcities you would expect.

We know that 40 cards in print run No. 1 were printed two times or three times, which would yield a ratio of 150 percent if all the cards had survived and been sent to PSA. However, the actual ratio is only 116 percent. This could be interpreted as collectors work on complete graded sets, and they get one card of each graded regardless of how difficult they were to acquire or, perhaps, not all the extra printed cards survived.

Collectors dumped them or moms threw out the duplicates. The range among individual commons from each average was as much as 35 percent one way or the other. The PSA population numbers don’t point to short prints being very scarce. They don’t even indicate that the last printing was very scarce compared to the first two printings.

Mathematically, since there are only 54 players in the last run compared to 80 players in the first run, the number of cards produced of each player would have been the same had Topps produced roughly one-third fewer total cards in the last run. Scarcities wouldn’t be obvious until Topps cut their production by more than one-third.

Hal Rice gets promoted 62 years later

Despite the lack of a direct relationship between the PSA numbers and the print run quantities, I did find some unusual results, which I used in my assumptions. In the second print run, I was missing two black-based cards that were justified on the left to include in short print cards. The average number of each second run SP card graded by PSA is 336. Hal Rice #93 is listed as a DP. DPs average 367 graded cards. Hal Rice turned out to be the card with the least number of grades in the entire set; only 259 Hal Rices have been graded. Hal fit the bill to get promoted to SP status and I inserted him nicely into my hypothetical print layout. Willard Marshall was the next most likely DP candidate to get promoted based on population numbers, so he joined Rice to create a logical layout.

EBay listings

In addition to the PSA numbers, I looked at current eBay listings for cards in the fourth run. On average, the entire fourth printing had 52 listings for each of the 54 cards in the run. However, the range of listings was considerable. There were only eight listings for short prints Willie Miranda and 14 for Dixie Howell, but there were 171 listings for Joe Coleman, 158 for Al Sima and 141 for Mike Sandlock. Miscuts of Sandlock, Coleman, Roe and Woodling next to cards thought to be short prints make it highly likely that these are four of the six replacement cards. I picked two more players: Lindell and Sima because of their high population reports and their base colors and alignments matched what was needed. Erautt, Hemus and Shantz also had high PSA populations and eBay listings and might have been among the six replacements instead.

The last print run replacements

Absent any uncut sheets or significant inventories, the price guide editors thankfully avoided trying to make a distinction between third run cards, which were likely printed either three or four times each. I think they should have refrained as well from guessing about the fourth run scarcities, except for finding the replacement cards, which were printed six, seven or maybe even eight times.

In my theoretical layout for the fourth printing I have Coleman, Sima, Roe, Woodling and Lindell printed seven times; Sandlock printed six times (since he is found next to two other cards thought to be printed three times); 15 players printed four times; and the remaining 33 players printed three times. However, various other combinations are possible depending on what the Topps layout people were thinking, and when they went to lunch.

Other oddities

Printing differences exist for a few cards and are of varying levels of significance. In addition to the other problems on Sandlock’s card, there is a version where the background is washed out on the left edge. Shea and Schultz have some blotches that come and go in their sky backgrounds and Fridley’s “r” in outfielder disappears sometimes. Mizell’s Cardinal logo is always found with black birds rather than red birds. Pete Runnels’ card pictures Don Johnson. Satchel Paige’s name is consistently misspelled Satchell.

Card backs

Topps introduced cartoons on the backs of the 1953 cards, a feature which continued, with some interruptions, until 1983. The “Dugout Quiz” questions were always informative and independent of the player featured. Young collectors were quizzed on rules, terminology, records and baseball history. Berger played it safe again by using “past year” instead of “1952” to describe the players’ recent statistics, just in case Topps had to keep selling these cards beyond the current season. You can actually read the facsimile autographs on the back of the cards. Berger must not have given them their $100 fee unless he could read their signatures?

Conclusions

– Arranging 1953 Topps can be fun, and we need those six missing players to have everything appear nice and logical.

– Price guide identifications of SP and DP can be misleading. How about LP (long print) instead of DP? It is the opposite of a short print. Another designation used by some collectors is over-print.

– Price guides and seller prices for commons may not have any direct relationship to relative scarcities.

– Two cards identified in price guides as short prints in the 2nd run probably aren’t, and two other cards identified as long prints are likely short prints. I’m betting that one of them is Hal Rice.

– The 4th print run likely had six players whose cards were printed six to eight times. Mike Sandlock, Joe Coleman, Preacher Roe and Gene Woodling were probably four of the six.

– The 4th run is a continuing puzzle. The PSA population numbers don’t point to any great scarcities, and the SP or DP designations should be removed, just like they are treated in the 3rd run. Once known, the six players printed six to eight times should be shown as “long” prints.

– After all this, Sid Hudson’s red edge and Bob Oldis’ black edge are still just miscuts, although you can find a Mike Sandlock miscut with a black border or with a red border.

We need to find more miscuts or uncut sheets to finish the puzzle of 274 players placed on 800 cards (four print runs of 200 cards each). Lew Lipset was looking for the same type of additional clues in his 1984 article. No such clues surfaced, according to a recent contact with Lipset, but there is still hope. Keep an eye out for those miscut cards.

My thanks to Tom Billing and other collectors who searched for miscut cards to work on the puzzle with me. I will report any new information received from readers. I expect other collectors have noticed some of the same issues and may have found some other pieces to the same 800-piece puzzle.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to Sports Collectors Digest and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.