Autographs

Look for telling signs in historic signatures

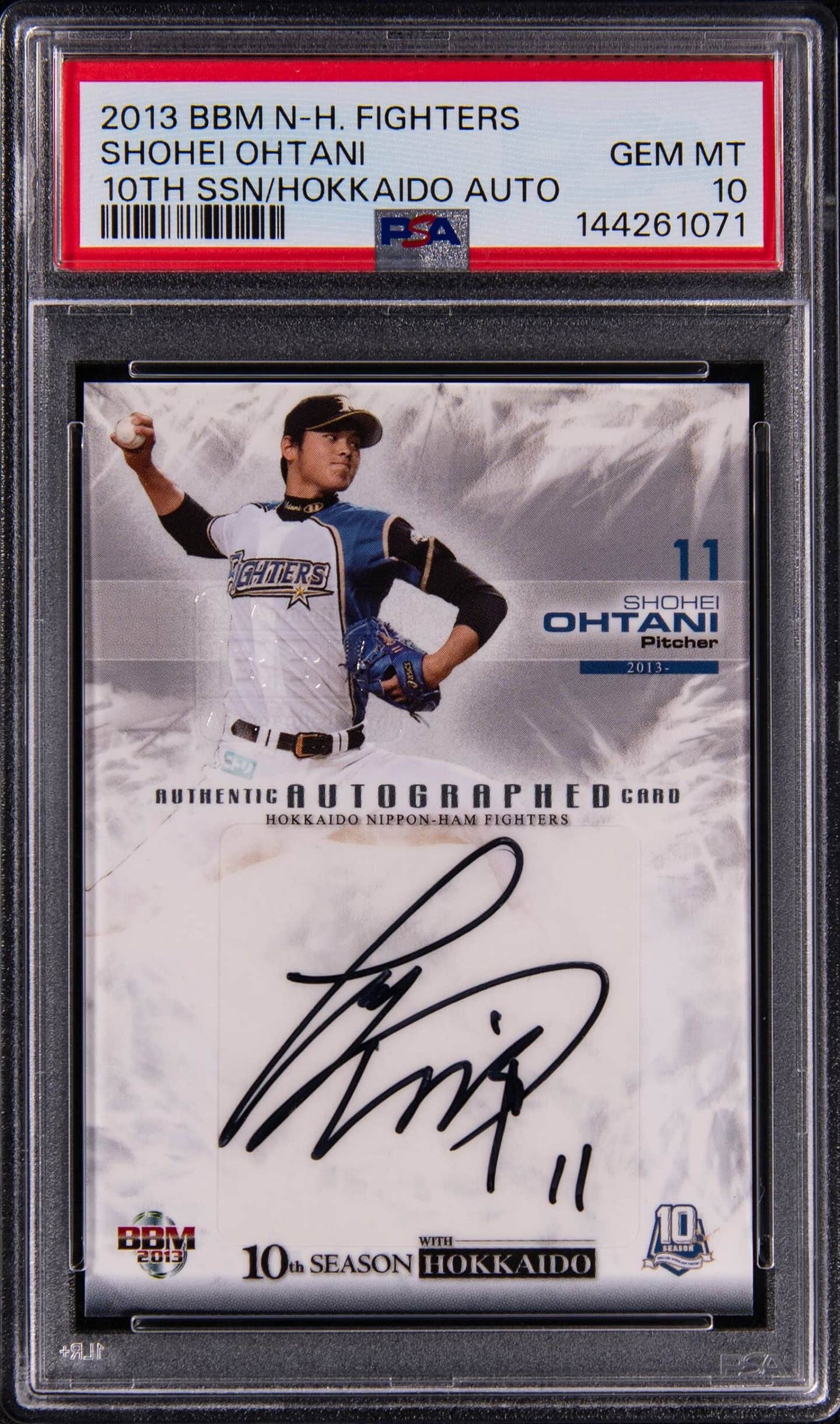

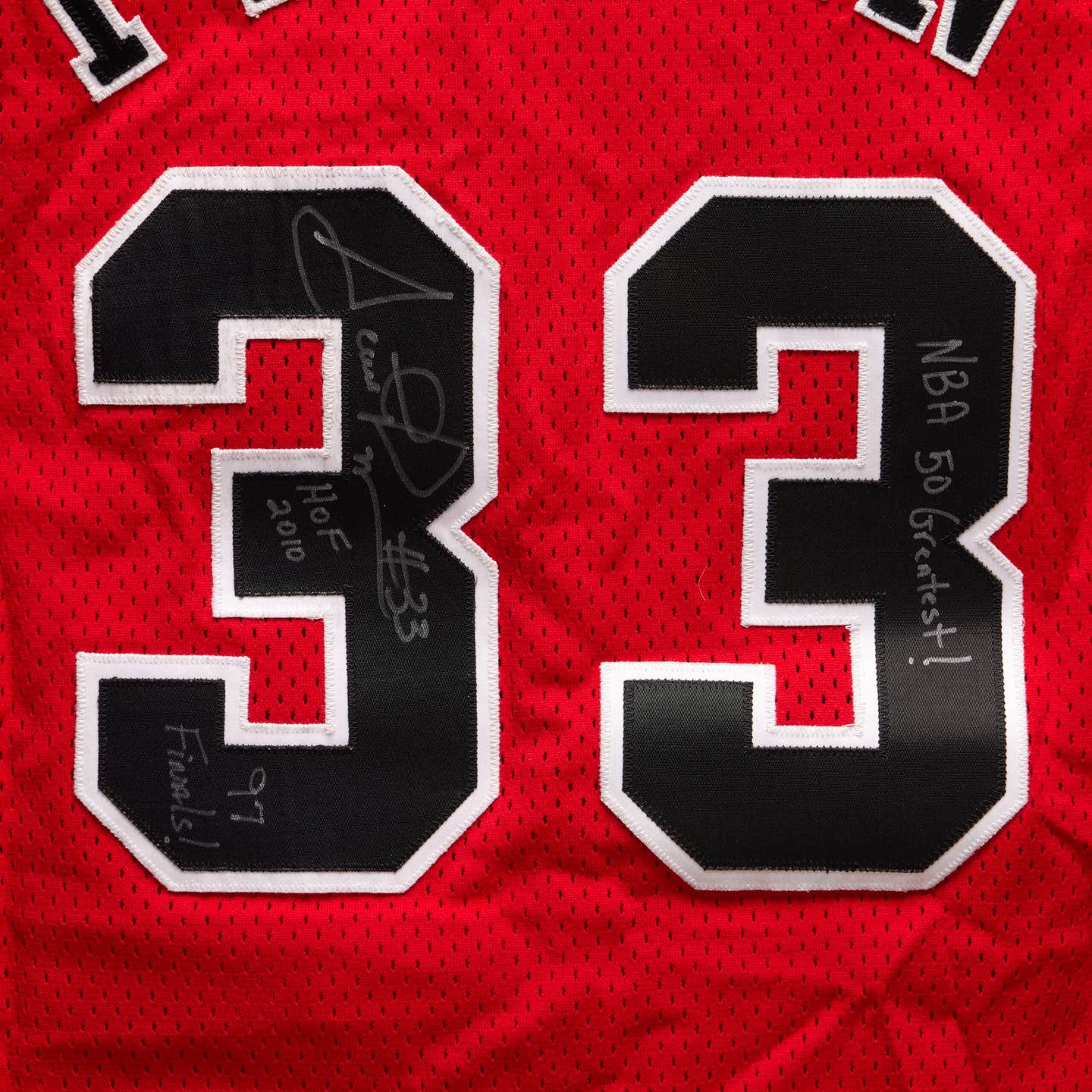

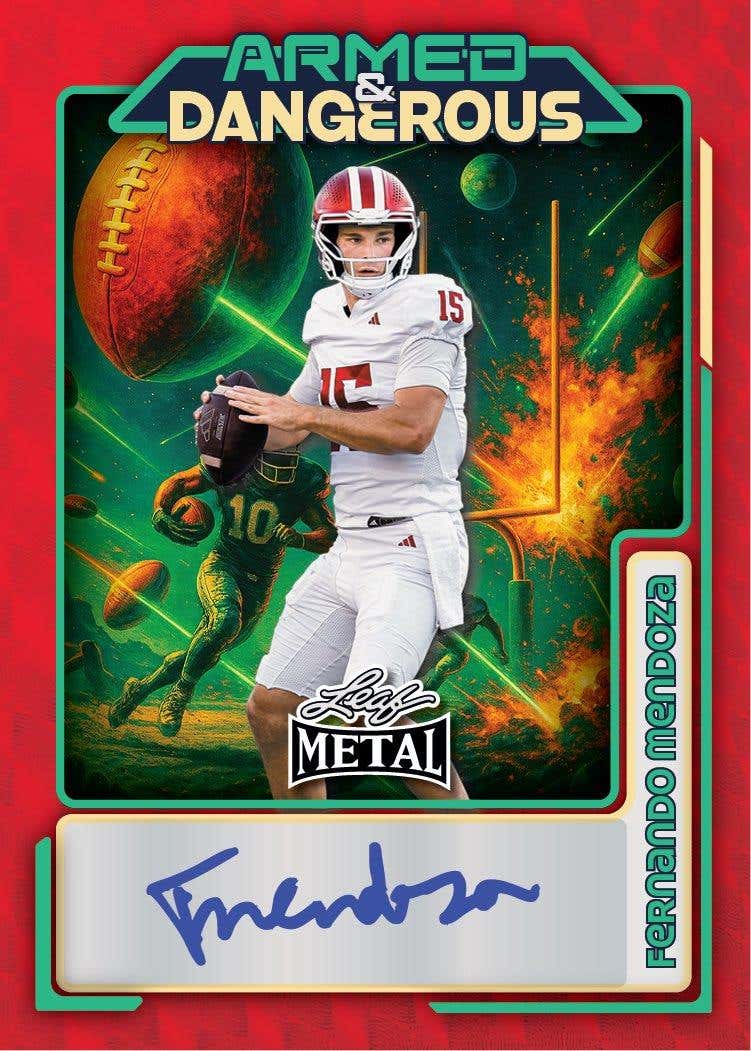

One thing I can say with certainty about authenticating autographs is that experience really counts. I can also safely say that unless you sat there and witnessed an autograph being signed, any authenticator that is being honest will tell you that their certificates of authenticity are really an educated, well-considered opinion — the keywords being “educated” and “opinion,” and that brings us back to experience.

You cannot learn how to tell a good autograph from a bad one by reading a computer scan, and you can’t simply match it from a few examples printed in a book. It takes knowledge, experience, magnification, special lighting and a certain amount of trust.

Pegging a good signature versus a bad one is, at best, an inexact science, and I would like to share some of the things we look for and some of the tricks that the forgers try to play on you.

Know the situation

Sign your own name 10, 15 or 20 times, and you’ll see how your signature differs from the first to the last. The situation in which an item was signed is really the key. Was the signer in a hurry? Were they signing in bulk? We have documents from Score Board showing sessions where Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Joe DiMaggio and others signed hundreds of documents in a single session. Were they pressured? Were they even sober? You need to understand the situations, and you need to look for certain tendencies in celebrity signatures that seldom change.

On the other hand, if all the signatures look alike, then more likely than not, it is because someone has practiced and practiced the art of copying and now has gotten it down pat. Joe DiMaggio was once quoted as saying that the forgers were so good, he couldn’t tell a forgery of his signature from a real one.

Some of what you find is so subtle that you can’t be sure. Other times, what they try defies common sense, and you just have to laugh.

You learn to look for all sorts of things, such as does the signature appear to be spontaneous? Is it too large (copies often are)? Was it drawn so slowly that the ink spiders or puddles? Are there changes of direction in the signature itself? Does the pen match the paper?

The writing implement is certainly a key. We often see small souvenir bats signed in felt-tip pen by players long deceased when doing so would have been impossible. We have seen dead-on Babe Ruth signatures signed in Sharpie fine-point pen on bats and balls. We have seen Lou Gehrig signatures signed in ballpoint pen. None of that is possible.

Every member of the Baseball Hall of Fame could have signed in either pencil or fountain pen — or other more primitive dip pens — but the conventional ballpoint pen was not in wide use until 1944 when it was adopted for use by the U. S. Army (despite having been patented in 1937). Fiber-tip pens first hit the market in 1951, but they were strictly for commercial use as consumer goods markers. The Japanese enhanced the idea and made it a commercial writing implement in 1964, but it wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the Sharpie became popular.

Helpful tips

There’s no doubt that despite the FBI crackdown in recent years, the remaining forgers are getting better and more skilled, but here are some common sense things you should look for that will help you avoid getting stuck.

If someone offers you a Ruth signature with “Babe” in quotes, be wary of that. He stopped signing that way in the mid-1920s (according to the curator of the Babe Ruth Museum), though some very good forgers are apparently unaware of that.

If someone tries to sell you a Philadelphia Athletics team ball with Connie Mack’s signature on the sweet spot, odds are that Mack’s signature was a clubhouse one (signed in most cases by infielder Wayne Ambler in the late 1930s and coach Dave Keefe, until Mack quit managing in 1950.) Ambler told me that story years ago, and a real tip-off on Keefe-signed balls is that his name is directly under Mack’s. He signed them both at the same time.

And speaking of “ghost signers,” we recently were presented with a beautiful Lou Gehrig-signed letter on his personal stationery reading Larchmont, N.Y., and dated July 15, 1939. The signature was very close to how Gehrig signed early in his career. And when we compared it with exemplars, we were struck by the strong resemblance to the way his wife, Eleanor, signed the Gehrig name. In fact, it is well known that later in Gehrig’s life, he dictated his letters to her and then she signed them.

Ruth’s wife, Claire, also signed her husband’s name to things, and Joe DiMaggio’s sister, Marie, is also known to have signed things for her famous brother. Were they trying to fool anyone? I doubt it. More likely, they were signing the famous player’s name to make a fan happy. After all, in those days, there was no premium put on an autograph.

Autograph collectors are pretty familiar with Willie Mays and his diagonal signature, yet back in the mid-1990s after spending a whole day signing his name at Mickey’s Place in Cooperstown, N.Y., my partner, Jeff Stevens, asked him to sign a 1099 form acknowledging the receipt of his hefty daily fee. Mays did so and reverted back to a 1950s scroll not seen since his early baseball cards. Most authenticators would have ruled that signature bogus, yet Stevens was there when he signed it. So be careful.

Make sure that the signature is on a ball that was in use during the player’s lifetime. You’d be amazed how many forgeries end up on baseballs that couldn’t have been signed by them. Also be wary of pristine white balls with vintage signatures where the logo and manufacturer’s name seems to have faded away. Forgers have been known to bleach off the telltale markers so that they can produce vintage-looking signed balls of Hall of Famers.

The converse of that is the very dark, supposedly vintage balls that have several coats of shellac on them. Again, common sense begs the question – why would anyone sign a dark brown baseball?

Another area to be careful in is the purchase of signed Hall of Fame postcards. We recently had such a card signed by Jimmie Foxx (the signature looked good) that he would have had to come back from the grave to sign. Albertype black-and-white cards were the first – and there were a small number of enshrined players included in those cards, though they could not have been signed by Johnny Evers and Paul Waner. These are followed by the Artvue postcards, then Dexter Press, Curteichcolor and Mike Roberts plaque cards, and they are the ones bearing impossible deceased player signatures the most often.

When Stevens was merchandising director of the Baseball Hall of Fame, he had the date of production added to the backs of all Mike Roberts Hall of Fame cards to prevent future forgeries.

We are very wary of any signature on the back of a U.S. Government postal card that does not have a cancellation and an address on the other side. Years ago, it was common practice (I did it all the time) to send a self-addressed U.S. Postal card to athletes and celebrities asking them to sign and return it. I can’t imagine many scenarios where an autograph seeker would thrust a paid postal card in front of a celebrity, in person, and ask them to sign it.

Vintage postal cards are available, in bulk, on the Internet or in any decent-sized antiques shop. Also readily available are first-day covers with cancelled stamps on them. It isn’t all that hard to add a vintage signature to one of them and have an instant collectible.

Another red flag area is celebrity-signed Christmas cards – or portions of them. Like postal cards, vintage Christmas cards are available at antiques stores, from dealers in vintage paper products and on the Internet. It doesn’t take much skill to take an old card, dissect it and affix a bogus signature to give the card the “look” of something old and cherished.

A few examples of this that we have rejected include a Princess Diana signature on a Buzza Cardoza Christmas card that was last produced in Los Angeles in the 1960s. Even if it was a current card, one would have to wonder why Diana would have been sending cheap, boxed cards to anyone.

We have also seen Ruth and Gehrig signatures on similar Buzza Cardoza cards – which are available in bulk on the Internet. Imagine the scenario of Yankees management walking through the clubhouse and handing out cheap Christmas cards for their superstars to send to fans. You can’t imagine that and neither can I.

Another curious one was a Christmas card presented to us for authentication signed by both Ruth and Gehrig. Why would they have done that? They didn’t even like each other for most of the last decade of Gehrig’s life. Common sense prevailed on nixing that one.

Or how about the portion (one panel) of a Christmas card that we saw signed by Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh. What are the odds? Gable and Leigh, of course, starred in Gone with the Wind, but why, since they were married to other people, would they send out joint Christmas cards? Sometimes simple logic is enough.

A Christmas card purportedly signed by Rogers Hornsby was rejected simply because it isn’t likely that the grumpy Hornsby would have signed his whole name on a card that read, in part, “Merry Christmas with Love.” Had it been signed simply “Rogers,” we might have at least considered the notion.

Alphonse Capone Christmas cards are another curiosity and likely to be a fantasy. Did you know that he only signed “Alphonse” on legal documents? Had such a card come from him, it would have been signed “Al” (his public persona). As a passing note, the “a” in Capone always has a tail on it leading back to the capital “C.”

We were recently given a Grace Kelly signature on an unused 4-Cent U.S. Postal card. At first glance, the signature looked probable. However, after studying all the elements, we concluded that it was a forgery. The tip-off? The postal card. Grace Kelly married Prince Rainier in 1956 and forever ceased signing her name as “Kelly” for fans, opting instead for Grace DeMonaco. The postal card bearing this Kelly signature was issued in 1964.

A small Christmas card bearing the name of 1930s sex symbol Jean Harlow was presented to us for our approval. In doing our research, we learned that Harlow, who died very young, seldom signed autographs and that most signatures that were sent to fans were, in fact, signed by her mother. In our exemplar file, we have a few authentic Harlow example. This one matched none of them, but it was close to her mother’s version.

Marilyn Monroe, another celluloid sex symbol, is in high demand among autograph collectors. But you need to beware of her signature, especially if it is signed in red ink. Monroe’s studio sent red-ink secretarial-signed signatures in response to requests from fans for many years. Mostly, she signed in blue or black, but there are a few known legitimate Monroe signatures in red ink, so her signatures are still a crap shoot.

And speaking of ink colors, most legitimate (though not all, unfortunately) Ty Cobb signatures come in green ink. As auctioneer at the legendary Philly Shows in Willow Grove, Pa., in the early 1980s, I had the pleasure to auction a significant collection of Cobb-written memorabilia, and every piece was in green. Cobb was also a prolific letter writer, and many of his green-ink-handwritten letters are in private collections.

General Custer signatures show up from time to time. He usually signed “G. A.” Custer, not “General.” We got one signed “General Custer 1874,” which was possible, I suspect, had he been signing autographs for the Indians. Custer spent most of ’74 leading an expedition in the Black Hills of North Dakota.

Vintage pro model signed baseball bats – especially Louisville Slugger/Hillerich and Bradsby – should be carefully scrutinized.

In the early 1990s, the Louisville Slugger factory purged its warehouse of thousands of vintage bats. While I was vice president at Fleer, I was offered these bats in bulk as possible promo items and given a couple of dozen samples, which we circulated among our sales people. Ultimately, we declined, and Louisville Slugger sold them into the hobby.

Now a lot of those bats are showing up bearing the signatures of the player named on the barrel. A tip-off is that the darker color has been scraped off the barrel, and the signatures placed there. Imagine such a scenario actually happening – we can’t either.

Be careful of signed gloves, as well. We recently saw a beautifully signed Gehrig first baseman’s mitt. The problem? The Wilson glove he was supposed to have signed was not on the market until 1955. Gehrig had been dead for 14 years by then. Sometimes the forgers make it so easy for you.

Joe Jackson signatures are extremely rare and always controversial. Joe was unschooled and had a difficult time signing his name. His wife often did it for him. But Joe isn’t the only one in that category. Another is Hall of Famer Charles “Hoss” Radbourn, who died in 1897 (at age 43) after a career in which he won 308 games.

Uncertainty surrounds all Radbourn signatures because he didn’t even learn to sign his name until later in life. His friend William H. Hunter actually signed his contracts for him. One of the main problems is that forgers tend to place an “e” at the end of his name (as some branches of his family did). It is known that when he did sign his name, he signed it “Chas” or “Charles,” and hardly, if ever, “Hoss.” Yet some of those appear in the marketplace.

(Editor’s note: The image of Radbourn’s HOF plaque that appears on the Hall of Fame website includes the extra “e,” which might explain why forgers make the mistake.)

If someone offers you an autograph signed “Pud” Galvin, run as fast as you can. Galvin, winner of 361 games, is another tragic figure. He died in 1902 at age 45 and was so poor at his death that friends had to hold a benefit to pay for his funeral. He signed “Jas. F. Galvin” if and when he signed at all.

There are a lot of rock ’n roll forgeries in the market. The Beatles are frequently forged, but there are still more of them in circulation than the small Beatle collector clique would like you to believe. They try to control the market much in the same way the late John Henry Williams cast doubt on virtually every signature of his father that didn’t originate with John Henry’s organization.

If someone offers you a multi-signed item, make sure that all the signatures don’t have the same characteristics. We recently were given a sheet of signatures purported to be the 1927 Yankees. A little study showed that all were signed in the same pen, the same stroke and most of the letters had the same characteristics, even when the forger attempted to replicate the big names like Ruth and Gehrig.

We once got a Chief Bender baseball signed “Cheif.” It’s pretty certain that Bender knew how to spell Chief, isn’t it?

And speaking of Indians, Sitting Bull was a rather prolific signer (when he was with the Wild Bill Cody Wild West show and back on the reservation), but Geronimo was not. However, his autograph is sometimes forged.

When our non-sports business began to grow, we began farming out such signatures to a professional historic documents examiner in Philadelphia, and our own learning curve continued. Signatures signed in the right style but against the grain of vintage paper constantly troubles our expert.

Vintage paper, like other vintage greeting cards and postal cards, is readily available in the antiques marketplace. Another source of vintage paper is from the inside pages of antique, but otherwise worthless, bound books. Forgers buy the book for a couple of bucks, pull out all the blank pages and dispose of the rest. It is difficult to date paper beyond the century in which it was manufactured.

We have also learned that early autograph collectors had very little sense of history and blithely clipped signatures off letters and legal documents and mounted them in books – discarding, most likely, the more interesting aspects and historic values of the document the signature originally adorned.

As Dr. Mike Marshall, the well-known former Expos hurler once said (and I paraphrase), “Why would anyone want my signature? It is simply me signing my name to a piece of paper or something equally insignificant.”

Dr. Marshall, as a result, seldom signed, and his autograph became more valuable as a result.

Even though he was a brilliant man, he never understood the hero worship that has been long a part of our American culture. Those who do get it enjoy the hobby, and we, as lifelong hobbyists and authenticators, try to make it even more enjoyable for those who play by the rules.

{Ted Taylor has been a lifelong collector of baseball cards, autographs and sports memorabilia, and with his close friend, and cousin, Jeff Stevens, formed STAT Authentic in 2005. Ted was one-time editor and longtime columnist for Sports Collectors Digest and was the hobby columnist for The Philadelphia Daily News for a dozen years.}