News

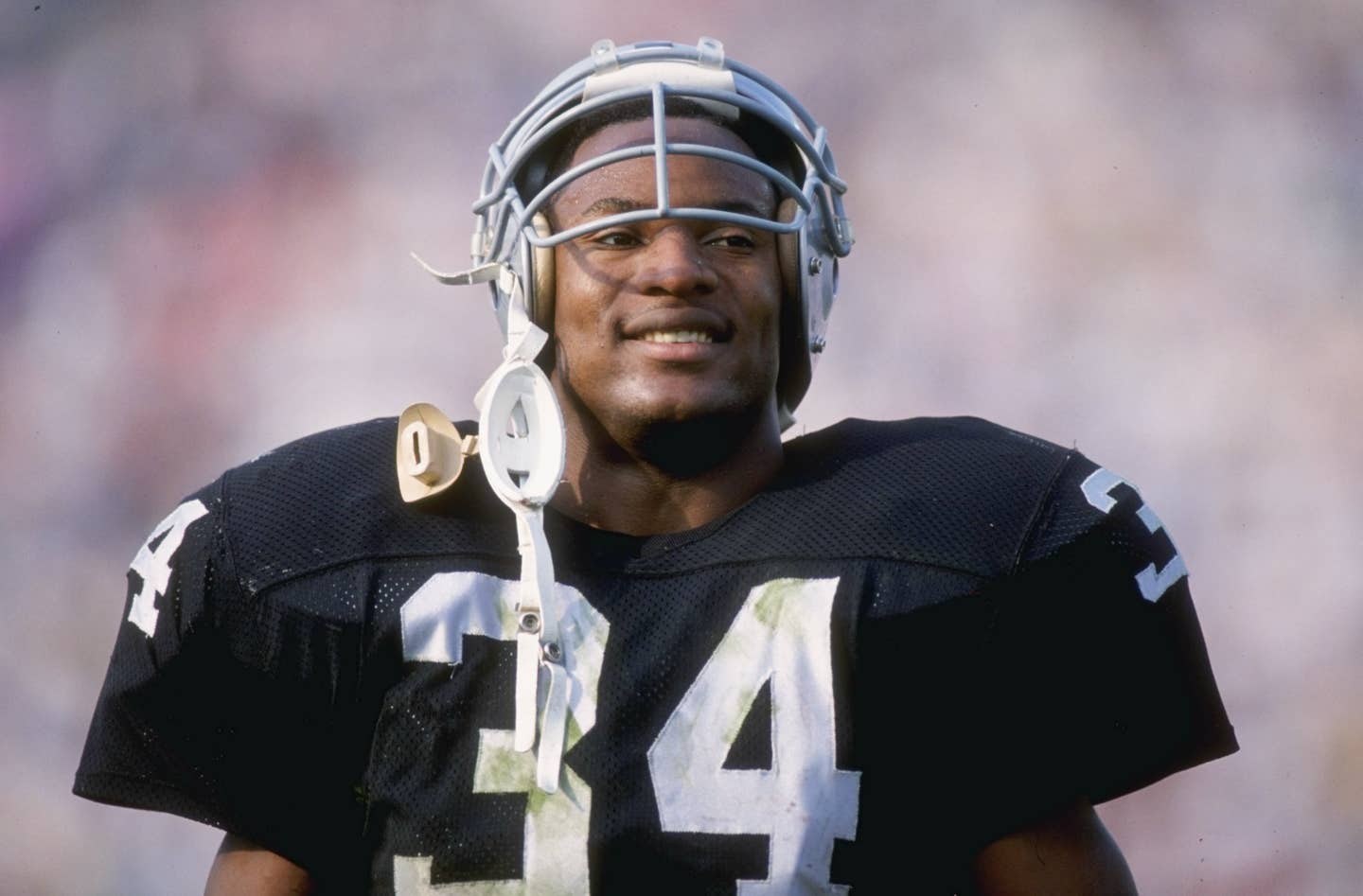

Do facsimile autographs have value to collectors? Bo (Jackson) knows

On Jan. 13, 1991, I spent the whole day getting ready. The Los Angeles Raiders, who are currently the Las Vegas Raiders but whom I called the Oakland Raiders both then and now, had a late afternoon AFC divisional playoff game against the Cincinnati Bengals.

I wore the Raiders parka I got for Christmas all through church and during the Giants’ 31-3 beatdown of the Chicago Bears. I held the Raiders troll doll I bought at Ben Franklin’s with my stocking money for the entirety of the 1 o’clock game, stroking its black, stand-up hair and hoping that Bo Jackson would run for 1,000 yards later that afternoon. (My perceptions of NFL rushing statistics had been largely shaped by the original Tecmo Bowl.)

At the time, I was a Raiders fan. The next fall, I was all “Hail to the Redskins.” The year after that, I went with the Cowboys. Soon thereafter, I gave up on the championship chasing of my pre-adolescence and became a Jets fan like my mom, and I’ve long since paid my debts of fair-weather fandom, thank you.

But on this mid-January day in 1991, I wanted nothing more than to see the Raiders pound the Bengals and make it to the AFC Championship Game, where they would crush the obviously overrated Buffalo Bills. The NBC affiliate in northern Vermont had the gall to show Buffalo every weekend. I hated the Bills for keeping me from my Raiders and couldn’t wait for Bo to make them pay. After he did a number on the Bengals, of course.

Which he did. Jackson got the ball just six times but rumbled for 77 yards in a 20-10 victory. On his final carry of the afternoon, which proved to be the final play of his NFL career, Bo Jackson took a pitch from Jay Schroeder 34 yards down the Bengals’ sideline. Cincinnati linebacker Kevin Walker brought him down awkwardly. Jackson tried hobbling back to the huddle but soon collapsed to the turf. The Raiders training staff helped him to the sideline with what proved to be a career-ending hip injury.

On Jan. 14, 1991, I woke up with a mission. I sat through a day of fourth grade, thinking about how I could help the Raiders out against the Bills. I decided the least I could do was write Bo some words of encouragement. In a sharply-worded note, I told him that, no matter what, he had to play in the AFC title game against Buffalo. The Bills were always ruining the 1 o’clock timeslot for us Vermonters and everybody in my home state would be a Raiders fan if only their games were on television every week. The only way that was going happen was if Bo Jackson gritted through the pain and beat Buffalo in the AFC title game. I encouraged Bo to do some jumping jacks in his free time. From my experience as an athlete, I explained, a couple of dozen jumping jacks always loosened me up.

It turned out that the Bills beat the Bo-less Raiders, 51-3.

I concluded the letter with my typical request for “an autographed picture, if you have the time.” Once I finished my missive, I convinced my mom to drive me to the post office to get this important piece of correspondence in the mail.

I put my letter addressed to “Bo Jackson, Oakland Raiders, Los Angeles Coliseum, 3911 Figueroa Street, Los Angeles, CA 90037” in the outgoing mail slot. Less than two weeks later, it turned out that Bo had found some time. Sort of.

I received a large envelope from “Club Bo” containing a brief letter explaining how “Bo gets a lot of letters from his fans” and I could write to an address in Alabama for a “Club Bo” catalog featuring all the latest Bo Jackson merchandise. The envelope also contained a photograph of Jackson in a bomber jacket with an obviously printed-on signature. The “Club Bo” letter asked me to accept this autographed picture as a token of Bo’s appreciation.

Over the next 24 hours, I went through denial, anger, bargaining, acceptance, and denial again. I decided that the only way I could prove to myself that Bo had sent me a real autograph was to bring it in for show-and-tell on Friday. I’d let a jury of my peers figure out whether this was actually Bo Jackson’s signature or an obvious facsimile.

The jury was unanimous in its decision. I went up in front of the class with my Bo Jackson picture and explained that while the autograph looked printed-on, it was probably real because Bo wouldn’t do such a thing to me.

“Pass it around the room, Clayton,” my fourth-grade teacher said, being one for hands-on learning. “Fake. Fake. Fake,” they all said, giving it one look and seeing that this picture was no more hand-signed than the diploma from Faber College I would one day buy at Spencer’s.

I didn’t care. I put my Bo Jackson picture in my autograph box alongside real ones of Dwight Evans, Lou Holtz and Nolan Ryan. Over the next few years, my pretend Bo Jackson autograph got a lot less lonely. I acquired a murderer’s row of facsimile autographs through the mail: John Elway, Jim Kelly, Joe Montana and several medalists from the ’94 U.S. Winter Olympics team.

Eventually, I genuinely came to accept these facsimile autographs as an artifact in their own right — a piece of sports memorabilia reflective of a particular time and place in my life. Moreover, I became grateful that these idols of mine even bothered to have someone in their employ acknowledge my letters and their imperious words of wisdom.

It turns out that such facsimile autographs are nothing new. Steve Widgerson of Global Authentics, one of the world’s foremost experts on autograph authentication, says that such printed-on autographs became commonplace beginning in the 1930s.

“Most have little value to autograph collectors,” Widgerson said, “but vintage photos, baseballs, lithographs and the like featuring facsimile autographs do have value in the collecting community.”

I asked Widgerson if public figures that send fans such printed-on autographs are trying to present them as the real deal or just acknowledging the letter with this small gesture.

“Both,” he said. “Some public figures will return a facsimile signature as a way to respond to the overwhelming amount of requests they receive.”

Some public figures, he said, use an autopen to mechanically sign their names. Some are doing it as a way to acknowledge their fans while others, he said, are being more deceptive.

“This would mostly be true in recent years as public figures are using the autopen machine in a deceptive way, offering autographed memorabilia for sale on their websites and delivering auto-pen signatures with no reference to them being facsimiles,” Widgerson said.

My facsimile autographs predate this phenomena. They reflect instead the desire of sports stars of my youth to acknowledge their fans in a small but meaningful way.

— Clayton Trutor holds a PhD in U.S. History from Boston College and teaches at Norwich University in Northfield, Vt. He is the author of a forthcoming book on the history of professional sports in Atlanta. He’d love to hear from you on Twitter: @ClaytonTrutor