Collecting 101

Cobb not the monster he’s portrayed to be

"I never saw anyone like Cobb. No one even close to him. When he wiggled those wild eyes at a pitcher, you knew you were looking at the one bird nobody could beat. It was like he was superhuman."

- Casey Stengel

It was said that he took pleasure in what was called in the early days of baseball "coming in with your steal showing." In other words, purposely sliding into an opponent who was guarding a base with his spikes high to maliciously injure the player guarding the base. He was an inherently evil man disliked and hated by opponents, teammates and even members of his own family.

It was said that he beat his wives, that he was a greedy miser, who trusted no one. Supposedly, he always carried a gun or a knife and was handy with both. It was rumored that he had once killed a man who had tried to rob him in Detroit in 1912. That, after amassing a string of records in a major league career that lasted 24 years, he became even more sullen, bitter, vengeful and violent. He was said to be a psychopath, prone to vicious rages, who died an alcoholic and alone. But how much of what has been written about Cobb is actually true?

Toward the end of a life ravaged by cancer, diabetes, alcoholism and a string of ailments, Cobb commissioned a then-unknown writer named Al Stump to be his biographer. Mainly, Cobb wanted to set the record straight and to have someone he trusted record his legacy in his own words. Stump would eventually became one of Cobb's companions during the final 10 months of his life. Stump did write the biography but years later, not until after Cobb had died. Stump needed money and wrote his own version of the life of Ty Cobb. He wanted to write something that would sell; he wrote a sensationalized version based on half-truths and outright lies.

Almost all of the legacy that exists of Cobb today, the legacy of possibly the greatest baseball player of all time, is based largely on the unsubstantiated accounts of his biographer and "friend" Stump. But how much of what we know about Cobb is true? The numbers in the record books are irrefutable and incontestable but the rest of Cobb's story bears closer scrutiny. But, before we do that, lets take a look at the author.

Stump was an unknown, lackluster and mediocre writer whom Cobb had chosen to write his baseball epitaph. There was a side of Cobb, rarely written about, that enjoyed helping the "underdog," whether it be a struggling young ballplayer or a struggling young writer. One of Cobb's closest personal friends throughout most of his life had been Taylor Spink of The Sporting News, baseball's premier publication. Cobb could have certainly used his friendship with Spink, his fortune and notoriety to hire any one of the countries best sportswriters of the day to tell his story.

Instead, he chose a struggling young unknown.

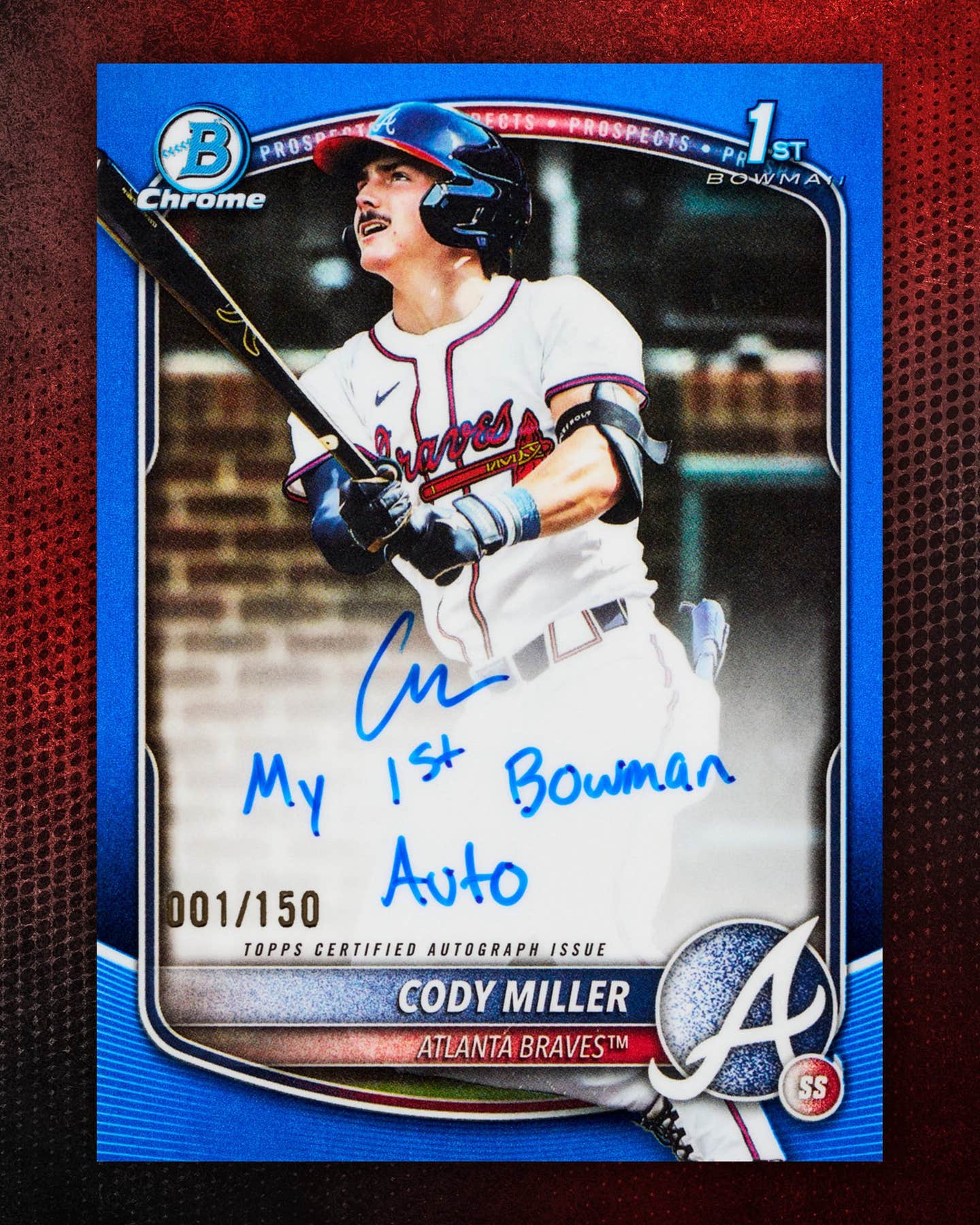

When Cobb first commissioned Stump he was seriously ill after becoming addicted to painkillers and a variety of medications. His decision-making powers were dampened by the disease that would soon take his life. His fierce pride fermented his determination not to have family or friends bear the burden of his final days. Enter Stump, who would become Cobb's chauffeur, confidant and companion. After his death, Stump claimed many of Cobb's personal effects and sold them into the then-fledgling baseball memorabilia market. He took clothes, personal effects, even Cobb's false teeth, which would surace in the hobby to some notoriety in the 1999 Sotheby's auction of the Barry Halper Collection.

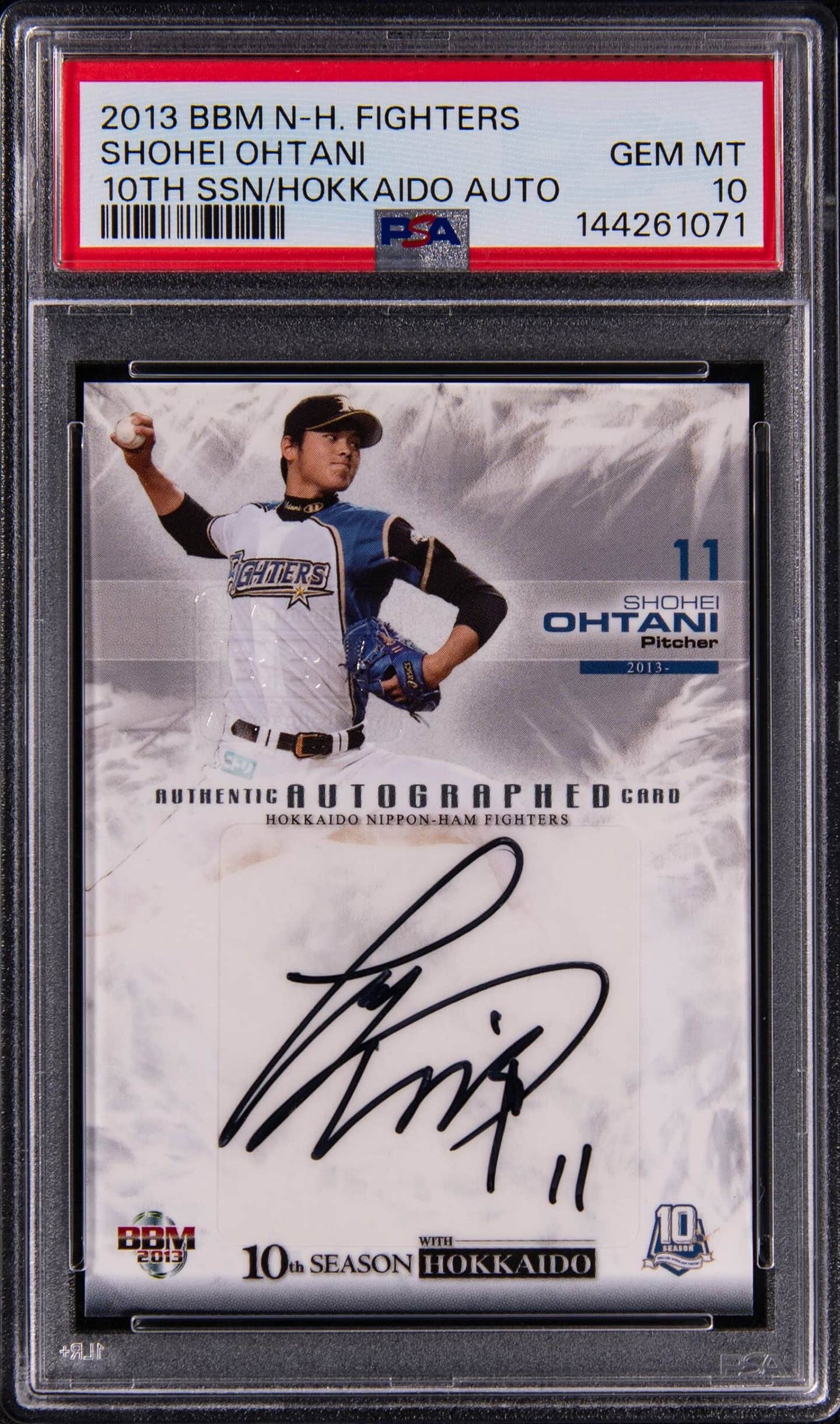

Strangely he also took with him stacks of Cobb's personal stationary bearing his letterhead. Cobb had been a prolific letter writer. Stump's motive for this would later become clear. Stump completed his book, blasting the memory of the man who had befriended him and sold numerous stories to periodicals and magazines, each more sensational than the other. Typed letters on Cobb's own stationary dated shortly before his death and signed neatly "Ty Cobb" began turning up in great numbers. They were sold to various autograph collectors, dealers and auction houses, selling for hundreds of dollars each. They were not signed by Cobb but by Stump himself, who by then could list the occupation of "forger" on his resume. This is the man whose accounts historians and fans alike have chosen to accept as fact. The "real" Cobb, while not a saint, was certainly not the demon he has been portrayed to be.

Cobb was one of the most fiercely competitive athletes who ever lived. He was a young man from a well-to-do Georgia family. Against his father's wishes he left home to become a ballplayer. Although he was talented, recognition did not come quickly or easily. In an effort to attract attention to himself, the young man began writing letters to the sportswriters of the day penned with anonymous surnames boasting of the incredible talents of a certain young man from Georgia.

The famed writer Grantland Rice began to wonder what all of the fuss was about and took notice. Soon the young prospect was on his way to Detroit and a tryout with the major league Tigers. But only weeks before his major league debut an incident at his family's home in Augusta would forever change his life and his way of looking at the world. His father, who he revered, was shot to death by his own mother with his father's shotgun. The real facts would always remain sketchy and Cobb himself would never discuss the incident, but it was believed that his father suspected that his much-younger wife was having an affair.

Cobb's father returned from a trip unannounced and in an attempt to enter the home through their second-story bedroom window and was shot as a prowler. Before his own death, Cobb remarked on his own amazing accomplishments by saying: "I did it for my father. I knew he was watching me and I never let him down."

Along with the emotional scars left by the incident, Cobb carried permanent scars on his legs from being spiked and other incidents and from sliding. He also bore a large scar on his lower back as the result of a knife wound in Detroit in 1912. Three men who recognized Cobb and knew he was prone to carrying large sums of money attempted to rob him. As testament to his ferocity when challenged, Cobb, bleeding from his wound, chased one of the men into an alley and administered a beating with a Belgian-made Ruger pistol that he carried with him. The next day, still bandaged and bleeding from the wound, Cobb hit a double and a triple before being forced to seek medical attention.

But make no mistake about it, there was a gentler side to the man that history has chosen to portray as a monster. In the early days of a fledgling new Georgia soft drink company called "Coca-Cola," Cobb invested heavily in stock in the company and encouraged other players to do likewise. Those who did became rich as a result of his tutelage by investing in the stock market.

He was especially kind to children and encouraged young men to pursue careers as ballplayers, even taking the time to write lengthy letters of recommendation to club owners and managers extolling the virtues of their play. In 1935, a young ballplayer who had been tearing up the Pacific Coast League was being offered a contract to play for the New York Yankees. That slugger's name was Joe DiMaggio. Cobb, who was friends with fellow San Franciscan and former ballplayer Lefty O'Doul, had seen DiMaggio play and was aware of his talents.

He was also aware that the $5,625 salary the Yankees had originally offered DiMaggio was ridiculously low. It was only slightly more than DiMaggio had made playing for the Seals in the Coast league. DiMaggio asked his friend, O'Doul, what he thought and Lefty suggested consulting with Cobb, who personally dictated the letter DiMaggio would write to Yankees' GM Ed Barrow. When the resulting letter from Barrow raised the major league offer almost $1,000 Cobb again dictated the letter of refusal asking for more money. Barrow eventually gave in and raised the rookie's first Yankees contract to $8,500 for the season, but it took Cobb's veteran major league savvy to do it.

Cobb was always accommodating and friendly to the many fans who requested his autograph. He would often send lengthy handwritten replies in answering questions about the great players of his day and offered tips on hitting and base running. He loved talking baseball and it is reflected in his prolific correspondence, sometimes with complete strangers. Stump insisted that Cobb was a miser who kept the letters received from fans and then burned them in his fireplace.

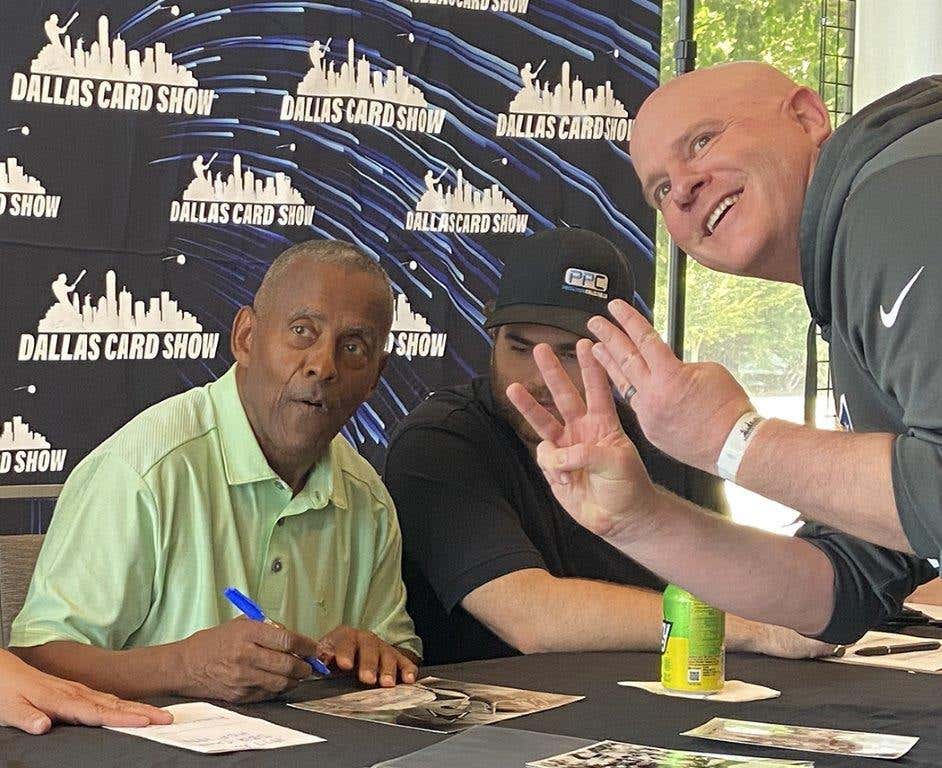

The fact is, even in 1958, an extremely sick Cobb wrote to his editor and friend Spink and said, "I am swamped with unanswered mail, I have no stenographer." Cobb was receiving an average of 300 letters a month and he felt compelled to answer them all. Long-time autograph collector Jeff Morey says of his meeting with Cobb in Cooperstown, N.Y., in the late 1950s:

"I looked around the grounds of the hotel where all of the players stayed during the inductions each year and finally saw Cobb sitting in the restaurant alone reading a newspaper. I approached him, baseball in hand, not knowing what to expect," Morey said. "He looked very serious and to my shock his breakfast of bacon and eggs arrived at his table at the same time as I did. I politely told him I'd come back later when he was finished eating as I didn't want his eggs to get cold. Cobb looked up, smiled, set down his fork and told me that signing autographs for young baseball fans was more important than breakfast," Morey said. "He took the time to neatly pen his name on my ball and then asked if I had anything else I'd like him to sign. I awkwardly produced a Hall-of-Fame plaque postcard and a couple of baseball cards. He signed those, too, as his eggs sat there getting cold.

"When he was through, he asked me about what position I played, my hobby of collecting autographs, and was genuinely interested in my opinions. I almost had to tear myself away as I felt so guilty intruding on his breakfast. It was only after all of my items were signed that he shook my hand, wished me a good weekend and began to eat his breakfast."

And this was the man Stump had referred to as "the most violent, maladjusted personality ever to pass across American Sports."

In my own personal conversations with Hall of Famer Bill Terry, the last National Leaguer to bat 400 in a season and a man who knew Cobb well, he snarled when I asked him if Cobb was as bad as the media and history had portrayed him to be.

"Cobb was a gentleman," Terry said "On the field was another story. He was a fierce competitor who hated to lose, but off the field he was a real gentleman. In all the years I knew him personally, I never even saw him swear when he was around women or children. All that stuff they wrote about him, especially after he died, was pure bunk."

Excellence and perfection in any endeavor is often met with jealousy and envy. There is no question this was the case with Cobb, who in a letter written shortly before his death said, "My real weak spot is unjust criticism, it hurts but I try and toss it off. What great thing have I done to cause my inferiors to criticize me?"

Cobb played 22 years of his ML career with Detroit, finishing up with the Athletics, who were then managed by the revered and respected Connie Mack. It was a habit of Mack's to sometimes position his outfielders from the dugout with a wave of his scorecard. Even the veteran Cobb was not immune and he always complied, respecting Mack's knowledge and authority. It was a union of mutual admiration.

After his career as a player was through, Tigers owner Frank Navin invited Cobb back as manager. Cobb's competitive fire remained and he worked tirelessly to help young hitters, such as future Hall of Famers Harry Heilmann, who won four batting titles, and Hank Greenberg, who led the league in home runs four times, achieve their maximum potential.

It is true that throughout his life Cobb remained critical of the way the game had changed. Like so many players of his day he had trouble accepting the new brand of baseball. Baseball was no longer a game of hit and run, bunting, stealing and winning a game a base at a time. The strategy of the game had changed and the long ball had dramatically altered the national pastime. Sluggers like Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx and Mel Ott ruled the day and there is no doubt Cobb resented the change and remained an outspoken critic of "modern ball" and its stars. But despite this fact, he still loved the game and was a frequent visitor and guest at many parks across the country at both the major, minor and even Little League level. At his own expense he visited hospitals filled with soldiers returning from WWII and later the Korean War.

His investments in the stock market amassed a fortune estimated to be worth more than $12 million. His monthly income from stock dividends, rents and interest exceeded $12,000. He maintained a home in Georgia, a palatial Spanish Villa in Atherton, Calif., in the San Francisco Peninsula and a hunting lodge on the crest of Lake Tahoe. He loved to hunt and fish and his West Coast residence afforded him the luxury of both. He became an avid golfer and a good one. He would often be paired against and took special pleasure in beating Ruth, who was an extremely good golfer himself.

He enjoyed gambling and bet large sums of money on his golf game. He was a scientific craps player and a "regular" in the casinos in Reno, where he would place $100 bets or more on a single throw of the dice. His favorite song was "Sweet Georgia Brown," and the bands in his favorite western haunts were quick to play it whenever he would arrive. Fans flocked to him and he enjoyed being remembered.

He was unselfish with his fortune and donated large sums of money to create the Cobb Educational Foundation to help finance needy children's college tuitions. He built and created an endowment for a first-class hospital, mainly to help the poor in his hometown of Royston, Ga. It should be noted here that these institutions benefited both white and black members of the community. This was the man biographer Stump had branded "one of the most viscious racists I'd ever met and the world's champion pinch-penny."

Cobb also sent money anonymously to many former ballplayers and sometimes their widows who had fallen on hard times. Hall of Famer Mickey Cochrane, who suffered a nervous breakdown as the result of a serious beanball incident, was the recipient of Cobb's generosity for years. Cobb's sister, Florence, was crippled and he took care of her until her death.

He paid regular visits to former ballplayers and friends like Nap Lajoie, Honus Wagner and Ed Walsh. He would routinely "hold court" with contemporary players like Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Joe Cronin, and although he stubbornly maintained that modern-day players couldn't compare to the Wagners, Speakers, Jacksons and Mathewsons of his day, he still insisted that Willie Mays, Williams, DiMaggio and Stan Musial would have been stars in any era.

In 1957 Cobb's health began to deteriorate. He suffered chronic diabetes aggravated by his drinking. He was treated with sulfa drugs but his condition was much worse than he was willing to admit. In 1958, he wrote to a friend and insisted, "I am not organically sick, just terribly weak." In fact, Tyrus Raymond Cobb was very sick. He had cancer, a condition he would battle for the next three years of his life with the same ferocity and tenacity that he had battled opposing teams during his playing days. But this was a battle he would not win and as a result, he began to drink heavily, routinely consuming more than a pint of whiskey a day. He relied on drugs to help him sleep and to ease the pain brought on by his cancer. It was during this time that his behavior became more and more bizarre as he fought a losing battle that would have claimed the life of a normal man years earlier. This was Ty Cobb.

The diabetes became so bad that he was forced to carry a supply of insulin and syringes with him at all times. Doctors at John Hopkins and the Scripps Clinic in California had warned him repeatedly that his drinking was deadly combined with the severity of his diabetic condition. The stubborn Hall of Famer scoffed at the thought. He disliked doctors and rarely followed their advice. He refused hospitalization, frequently slipped into insulin shock and was prone to dizzy spells and falling down. His diabetes affected his eyesight and California had turned down his request for a driver's license; he hadn't bothered to apply in Nevada.

In numerous correspondence with friends during this time he complained of a nervous disorder. "Don't increase my tension" was his common phrase and would frequently preclude violent outbursts. He didn't want the public or even members of his own family to realize the severity of his condition. He scorned sympathy from anyone, especially those closest to him and in these his final days he drove many of them away.

His cancer worsened and he had most of his prostate removed and it was found to be malignant. The cancer was spreading into his back and down into his pelvic area. He took Darvon and codeine for the pain, combined with bourbon, scotch and gin, now by the quart. Because of the codeine and lack of adequate diet, he would sometimes go days without eating. The simple act of relieving himself caused excruciating pain and his sleep was erratic. Once, en route to Lake Tahoe, he stopped for the night in a hotel near Hangtown, Calif. A loud party in a room nearby disturbed him and after a heated exchange with the revelers he fired two shots in the air from his ever-present pistol. The party quickly disbanded. The shocked hotel manager arrived at his room and was told loudly by Cobb, "I'm a sick man and I need my sleep, I want it quiet." Cobb explained that he was an honorary deputy sheriff of California. The police were not summoned.

He became more and more prone to fits of rage, lashing out at waiters, waitresses, hired help and old friends. "Don't increase my tension," he'd warn. The fact that Cobb was still walking around at such an advanced stage of his terminal illness was amazing considering he would be shooting craps all night in Reno, attending spring training games in Scottsdale and major league games in San Francisco. He was a medical marvel. In time, however, the pain became too much even for Cobb. He was admitted to Stanford Hospital, one of the largest and highest-rated medical facilities in the country. There he received massive doses of cobalt radiation to fight back the cancer which was now consuming his body. The hospital refused Cobb's request for whiskey so he had bottles smuggled in and drank it from the water glass on a bedside table that contained his false teeth. Cobb reveled in the subterfuge.

Knowing it was close to the end, he summoned up the strength for a visit to his native Georgia. "I want to see some of the old places again before I die," he said in December of 1960. In Royston, he sought out some of his friends, those closest to him, the few that he hadn't managed to disassociate from, before heading to Rosehill, the town cemetery. He climbed a hill as light snow fell and dusk approached. His gravesite was not difficult to find. He had commissioned one of the largest mausoleums in the cemetery. He stood at the entrance a large marble walk in edifice with "COBB" engraved in large letters over the entrance. Within the tomb he looked at the crypts occupied by his father, Professor William Herschel Cobb; his mother, Amanda (Chitwood) Cobb and his sister, Florence. He knew that soon he would be among them.

He returned to California and was told by doctors there that the cancer had now involved his brain and they gave him no more than three months to live. The pain was intense and required heavy sedation. He contemplated suicide. "Is it better to die a little at a time or all at once," he wondered aloud. "Do you think they'll remember me? If I had this life to live over again I'd have done things a little different," he once told a visitor. "I would have had more friends."

On April 27, 1961, in Wrigley Field in Los Angeles, he threw out the first ball for the opening game for the Angels' expansion team. He had promised the team's general manager, Fred Haney, an old friend, that he would be there and he was, but he was too sick to stay and left after only two innings. It was his last visit to a major league ballpark. That summer he made his final trek east, back to where it had all began. On July 8 he sent Stump a photograph in the mail of the mausoleum on the hillside in the Rosehill cemetery in Royston, Ga. On the back of the photo Cobb had scribbled, "Any Time Now." Nine days later he died quietly in an Atlanta hospital.

More than 400 people turned out for the funeral in Royston. Most of them had not even been born when he took his first major league swing 56 years earlier. Most had never seen him steal a base or get a hit or ever known firsthand the ferocity with which he played, but they were there. Many of them had never known him, had never met him, but they were there. He had dominated baseball in the early 20th century and set a standard by which all of those who came after him would be measured.