Collecting 101

A collection – and a museum – like no other in the

Several months before the National Convention in Anaheim in late July, an invitation to the Mastro Auctions dinner turned up at the office. The dinner is by now a staple of the National Convention routine every year, with the hobby's elite wined and dined and otherwise entertained by the giant auction house. I ain't hardly elite, but I get to go along as a member of the media, and I was looking forward to the dinner as much as I was the National this year.

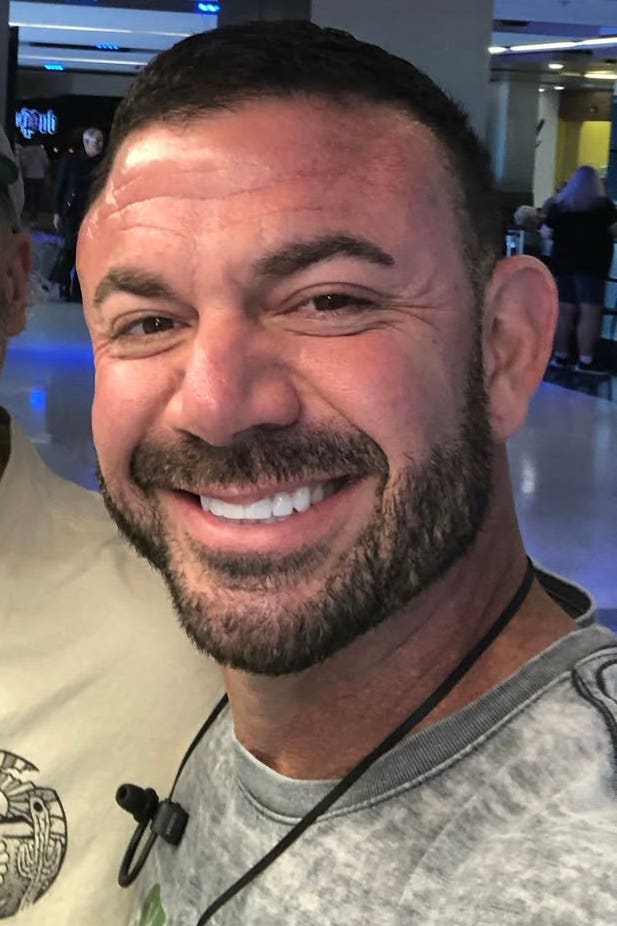

That was because the dinner was being held at Gary Cypres' Museum in downtown Los Angeles, and the before-and-after dinner festivities included the opportunity to view what may be the most highly regarded collection in the hobby.

I had known for several years that when major auction pieces were hammered down to an unidentified phone bidder, more often than not the guy on the other end of the phone was Cypres. So I walked through the front door of his museum with great expectations and then gleefully was knocked over by what I saw.

"You can't comprehend this place that's 3,000 miles away from the Hall of Fame. I am not worthy," veteran dealer John Brigandi said quietly as the first sections of the museum came into view.

"I am humbled," said noted authenticator Jimmy Spence, nicely summing up the views of many of the 125 or so assembled invitees who were bused to the facility that also houses Cypres' travel and mortgage brokerage company.

Low key and unassuming, the 62-year-old Cypres concedes now that, with the hoped-for opening of the museum to the public sometime next year, the idea of his remaining in the shadows is hardly workable or even good strategy.

"At some point it occured to me that if I were going to put together a museum I might as well get some publicity, as opposed to remaining anonymous."

Initially, before the museum was finished, he didn't really want the general public to know what he was doing. "I didn't particularly want to advertise that I was building a museum, until Stephen Wong came by and was writing the Smithsonian book.

Building a museum to display your collection is the ultimate hobby dream, one that yields varying levels of feasibility depending on a number of circumstances. Barry Halper tried for many years to engineer such a fate for his $40-million-plus accumulation before ultimately deciding to liquidate with the sale to Major League Baseball and the famed Halper Auction in 1999. The focus of Cypres' collection is vastly different from Halper's, but the grand vision of building a museum was no less daunting.

"In the beginning, I didn't know if I would follow through with it," Cypres said. "Everybody wants to build a museum, but few people ever actually do. Once, I had the concept, I figured I'd see where it would go. I didn't know if I wanted to commit the economic resources to it, and I had no idea whether I could do it myself."

That last statement sounds like an allusion to the financial undertaking, but it wasn't. It was a reference to the actual design and layout of the museum, which, it turned out, he managed with spectacular results, and this without any specific training in the field.

Though he has been collecting for many years, the notion of a museum started only about four years ago. "I had been collecting for years and the stuff was all over the place, so I just decided I would build a museum."

Cypres said he probably had about 50 percent of what was initially displayed in the facility, and then started to buy additionally. "It was always memorabilia for me collecting as an adult, but I collected cards growing up as a kid in the Bronx, a diehard Yankees fan. I grew up primarily in the Mantle era (Cypres was born in 1943).

"From the time I was 8 years old, Mickey was just coming in and Joe DiMaggio was leaving. So I caught the 1950s, which was a magical decade for the Dodgers, Giants and the Yankees."

He even went to all three stadiums, and the museum boasts some spectacular pieces from all three, including the first ball thrown out at Ebbets Field, which gave rise to his Dodgers Room.

His first love was baseball, his second love was basketball.

"I always loved posters and advertising display pieces, in addition to tennis and golf. Those are my main emphasis, and then as I evolved into the more American sports (in terms or origins), but my first love was advertising pieces." It kinda shows.

He was one of the early buyers of the big advertising display pieces, and then he started branching out.

"I have a very wide appetite for stuff. I like color, and that's one of the things that attracted me to the advertising display pieces and movie posters, especially the early pieces, where the colors are just stunning.

Those began to form the early part of the collection, and then he also liked equipment, live baseball gloves and football helmets, etc.

He started going to the National Conventions, with the first one in Los Angeles. "I didn't know anybody at all," Cypres continued. "It was the early 1990s, and it wasn't until the Copeland Auction and the early Sotheby's auctions that would be what we would call the modern age of auctions. I have really followed the hobby intensely since then, and I started to know more and more dealers."

As incredible as the quality and scale of his collection are, the presentation is just as overwhelming. The first thing you notice is how brightly lit it all is, a quality that lends a real air of fun and enthusiasm for visitors. It contrasts sharply with the traditional dark and shadowy world of big-time archival exhibition.

I don't believe there is one person in 100 who would look at what Cypres has created and not assume that it was designed and built by museum professionals. But no.

"We did everything ourselves. As my wife says, I have the ability to spatially lay out things," he said with a laugh. "When we go to the grocery store, I can look in the trunk of our car and say, 'OK, this is how we pack it.' Only in this instance, I look at a wall and I can see how everything has to fit."

And the self reliance bent goes way beyond even the planning and design. "We make all the displays. We decided we could build them all ourselves. And your material guides how you display things. I ask myself, 'What I am trying accomplish when I display something?' "

The building had been a retail store at one point, so Cypres even figured out even how the rooms would be partitioned. There wasn't some grand architechtural drawing at the start. "I said, 'Let's build a room here and see what it looks like.' "

Ultimately, you can't discuss and undertaking like this without poking into the financial numbers, but it's not an area that you will be steered into by Cypres. His love of the material and the hobby is genuine and paramount, and he only waded into dollars and cents at my prodding.

When I first entered the museum and saw even just a sampling of what was inside, I immediately assumed that much of it must have been on loan from friends and other hobbyis ts. It was a testament to the vastness of what was on display that one would assume that it couldn't all have been done by one individual, even one who had certainly earned a reputation as one of the hobby's high rollers. And naturally, I was wrong.

"I own every piece, except the Babe Ruth World Tour jersey," Cypress said, which he owns with his friend and fellow advanced collector Dr. Bill Sear of Atlanta.

He clearly doesn't put a good deal of stock in drumming up a dollar figure for the collection, but concedes that it's "tens of millions of dollars.

"I don't really keep track of what I spend, and I haven't had it appraised," he continued.

"My motivation wasn't to do it as an investment, and it probably wouldn't even pay as an investment, in part because I am utilizing a very valuable building that I own as a museum and getting no return on that. And no return on the stuff that I own, so when you put the two together the economic investment is quite sizable and you get no return on it.

"It's clearly, from my perspective, a labor of love."

The Moment of Truth

Cypres is talking to the City of Los Angeles about opening it to the public, now in the final legs of reviewing things like conforming to fire regulations. They have been working with the city for more than six months and expected some kind of word by the fall.

They have 125 parking spaces, and they will change the facade at some point. There's no indication at this point that there is a museum there. "Remember, if there is a good restaurant in town, people will find it, and they don't care what it looks like on the outside," he reminded. "Word of mouth and advertising will take care of it.

"I will change the facade, but do I have to? No. My attitude is, people will come. And I believe that they will enjoy it. Get the inside right, and the outside will take care of itself."

He hopes to open within the next year. "And when all that gets done, I have to sit down and decide if I really want to open it up to the public or keep it as a private museum. That's the big decision."

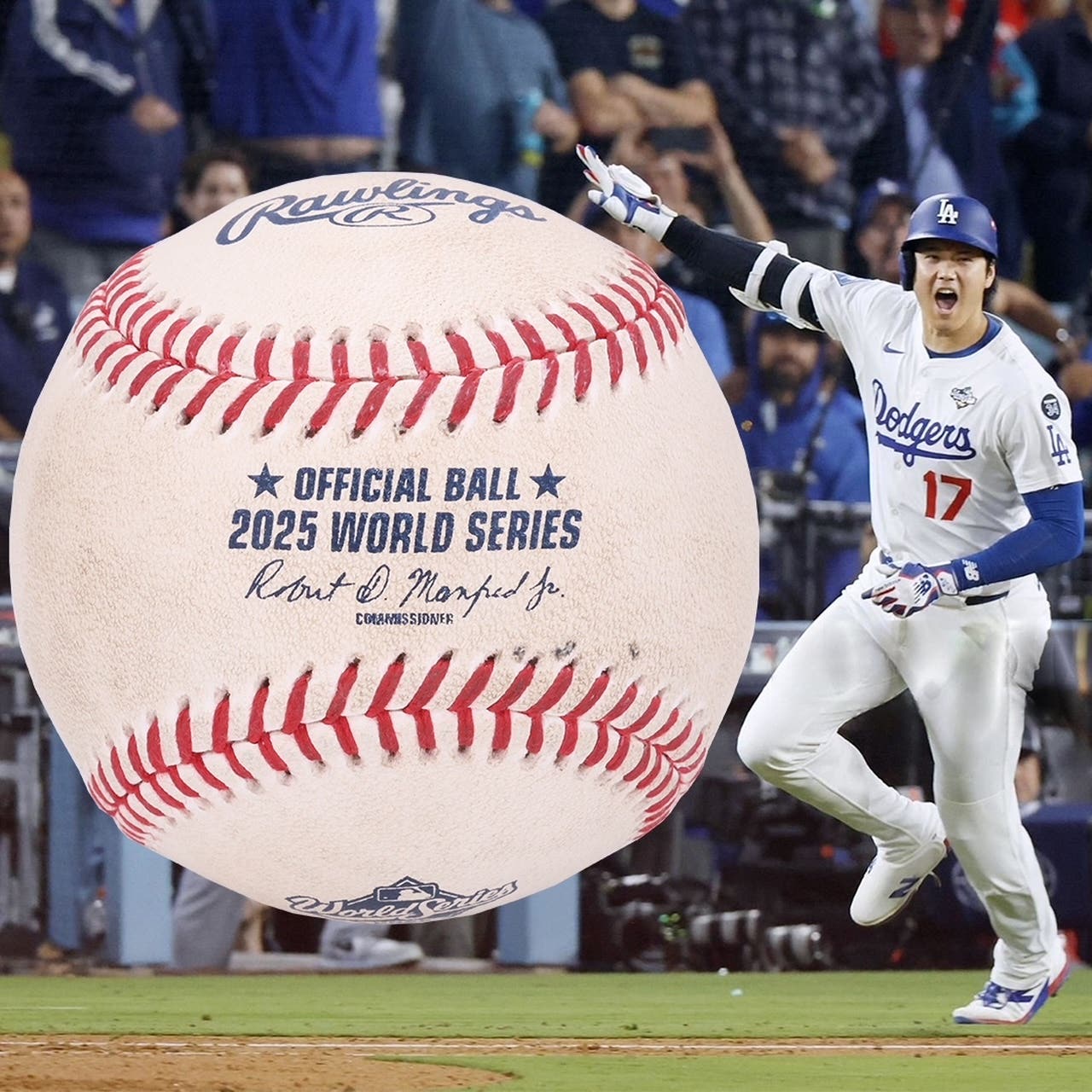

Yeah, I think he's managed a bit of an understatement there. It would seem glib and facile to dub it "Cooperstown West," and indeed it may well serve to address some of that for Left Coasters who can't make it all the way to Central New York, but the differences between the two are nearly as pronounced as the similarities.

"It's much different than Cooperstown. It's the most marvelous place, but it's a hall of fame for players. Basically, it was displays of people. It didn't have the color that I particularly liked," said Cypres, not even bothering to note the obvious distinction between a museum that is just about baseball and one that focuses on baseball, basketball and football, along with generous genuflections to golf, tennis and biking, among others.

"My interest is more evolutionary. I like to see the evolution of gloves, tennis rackets, things like that, for people to see how those things changed over time.

"Cooperstown never told the story of baseball. It told the story of baseball through the players. Ken Burns told the story of baseball."

One of a boatload of charming qualities about Cooperstown is that the Hall of Fame is charged with telling the history of baseball without being a complete spoilsport about the myth of Abner Doubleday and the shenanigans of Albert Spalding that got the museum there in the first place.

"Spalding still has his last joke at the end of the day," Cypres laughed.

"I set out to create a different museum. I thought it would be neat to show the evolution of football and tennis, show some of the old uniforms, an abbreviated history of how the games began, like the true roots of rounders and cricket.

"And I also thought with my love of color that I would have the posters and advertising display pieces so that people who didn't even particularly like baseball could come in and say, 'Boy, look at those posters; they are nice.'

"So I set out to build a different type of museum. Obviously, nobody has the artifacts that the various halls of fame have, but you don't necessarily need to have that to create a visual envirnoment and have an impact. I wanted something that was eye appealing."

His museum is more consumer friendly for the less-serious fan, and Cypres notes that he also wanted people be able to go up to the stuff and look at it in a whole different kind of casual environment.

"I think even if you didn't like a particular sport, you can come through the museum and still enjoy what you see."

The movie posters and ad display pieces are obviously among his favorites, and he brilliantly uses the two stories of the staircase area to display some of largest, most colorful movie posters imaginable. "I wish I had more space to display them, because I have tons more," he said with another laugh.

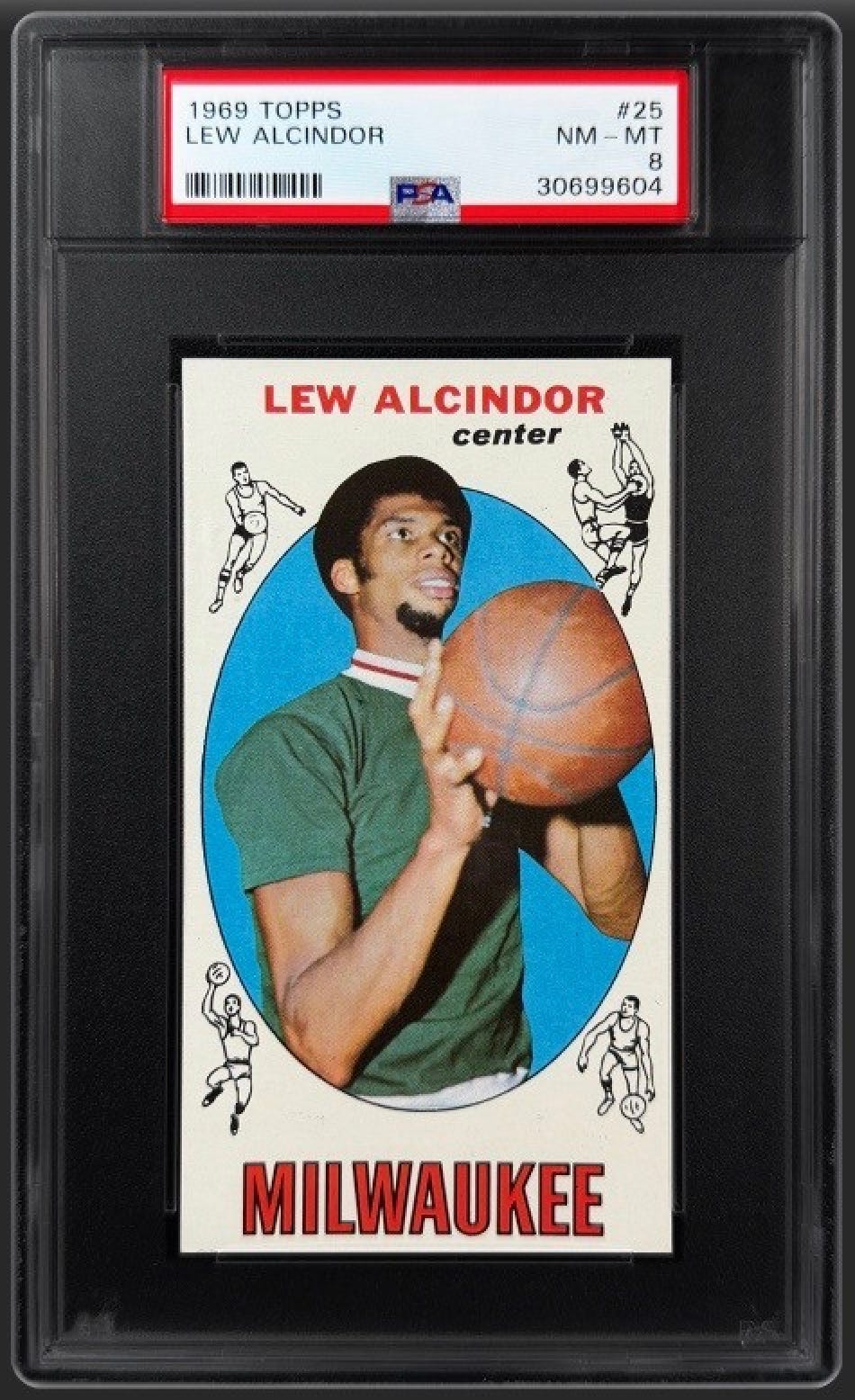

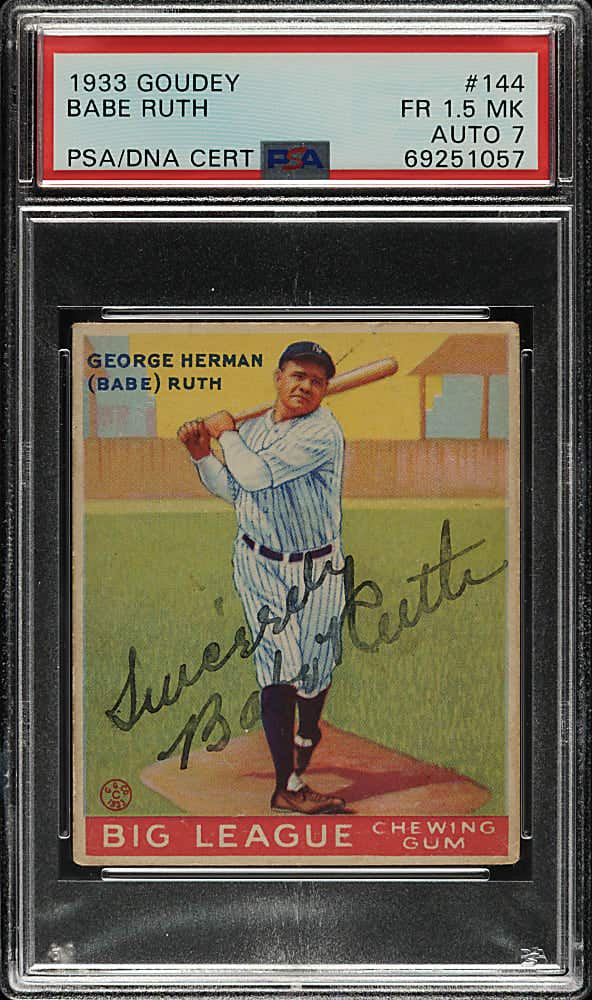

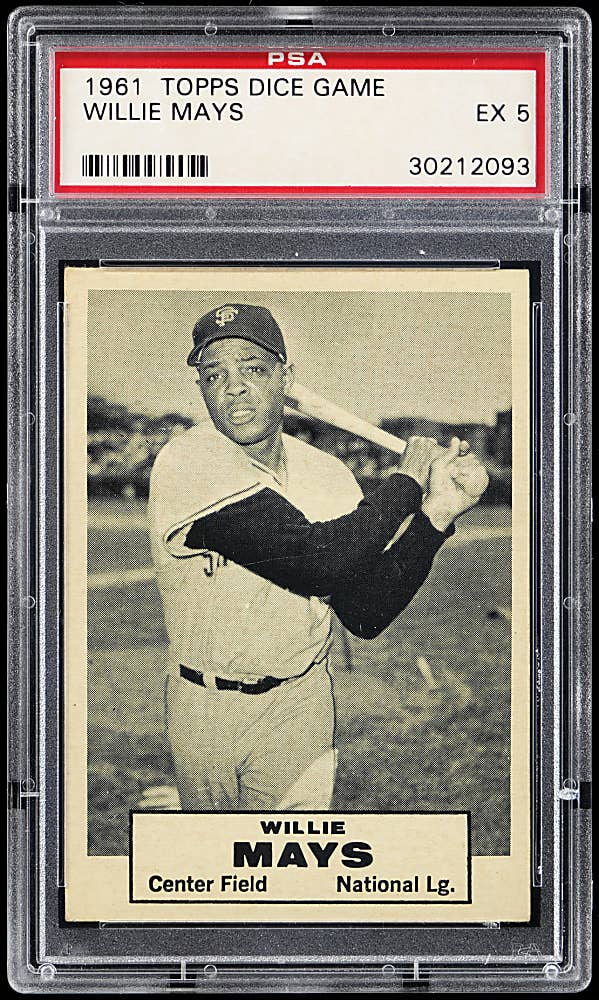

Cards get Reverential Nod

Baseball cards almost seem like an afterthought, albeit one with his usual flair for presentation in the most striking fashion. "The cards came as a result of my early posters. I had these Allen & Ginter and Old Judge posters with all these cards on them, and I figured I had all these posters that I might as well get the cards themselves.

"And that's one of the things I noticed about the Hall of Fame, that they didn't have any cards, because it's a Hall of Fame. So I tried to show people about the evolution of cards, going from the Old Judges and to show how the companies advertised them, so you can make a very nice room."

His informal attitude about the cards lends a wonderful freedom to the displays, unfettered by concerns about completing sets or organizing the cards in some arcane forumula. He just lets you get a look at some of the cards, including many that you see so handsomely depicted in the advertising posters in adjacent rooms.

"Who cares," Cypres said dismissively about queries about complete sets, or even the idea of obsessing about the condition of the cards.

"When you create a museum, you do so for your audience, so you have to balance your collecting instincts with your appreciation of what other people might like to see.

"So how do you do that? he asked rhetorically. Cypres said the truth is that most people couldn't care about whether the condition is VG or NM to MT. "What they really care about is what did the old cards look like? To accomplish that, I didn't need to buy high-grade sets. In fact, sometimes the plastic takes way from the appeal. If you put all the Old Judges like I have on one sheet, it's much more dramatic than if you put all those plastic holders up," he added.

"So I set out to get good examples of the various sets and put them on the walls so people can see how the cards changed, and then tie it in with a little history relating to the tobacco companies, how they began, how they stopped when the consolidation of the industry came about, and then started again in 1909."

And as it is for so many of the big-time collectors, the fun stopped sometime around the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.

"Once the modern era began, the cards became less attractive to me. There were no hand-painted cards, they were just spun out by the millions," he continued. And remarkably, his definition of modern is probably a good deal more restrictive than most people's. While some people might consider the "modern" era to be post 1981, his threshold is probably a couple of decades earlier than that.

Cypres doesn't even get that worked up about vintage Topps cards from the 1960s. "It's only the early cards that have the beautiful designs, the beautiful pictures."

He stopped around the 1950s.

No Playing Favorites Here

He c an't even begin to pick favorites out of the tens of thousands of items, nor does he even attempt such a pedestrian exercise. "I bought every single piece myself, and I love all of them. I can get as excited over a $20 poster as I will over a $400,000 bat," he insisted.

"And that's the beauty of what I do, to try and keep that level of excitement there."

One of my favorites was a room dominated by the remarkable paintings that Tony Piet commissioned and Mastro sold at auction several years ago. Piet was a major league ballplayer for the White Sox and when he retired he went into the used-card business and the commissioned the artist to do the amazing near-6-foot paintings to display in his show room."Everybody loves that room, it's truly special," Cypress said, using a phrase that probably could be repeated over and over.

These days he gets a lot of calls from collectors and dealers offering material, but he's very selective now because he doesn't have that much room left. And there's lots more where all this came from, meaning in various storage rooms around the building and at his home. He has, for example, a room with 20 other early bikes that aren't even out yet.

As he seemingly does with everything, he quite placidly faces what might be described as "The Barry Halper Syndrome."

Says Cypres, "What happens is that if you are not careful, people think that you are wealthy and they tend to jack up the price," he said, echoing a sentiment I heard Halper himself lament on more than one ocassion. "If you stay to the auctions, and just say no, then you're pretty safe, and I stick to all the quality auctions. I deal with all the major auctions houses and I've known them for a long time and I trust them to run an honest auction."

And a Pregnant Idea to Boot

He'd like to do a room for kids with all the board games, and the arcade games, and points to the noted expert and good friend, Dr. Mark Cooper, as a likely source for such an undertaking. But his idea along those lines is even more ambitious, which given all that Cypres has already accomplished, is hardly a surprise.

Eventually, he hopes to have a special section for exhibiting stuff from a number of other noted collectors on a rotating basis.

"One of the problems the hobby has is that most of the collectors have their stuff in their houses and they don't have any vehicle to display it. Wouldn't it be nice to have a way to say to all the collectors, 'Let me take your stuff and I'll display it for three months, or six months, like all the museums do.'

"That would be very good for the hobby, and very good for the collector because their stuff would be shown and they would be personally identified with it, adding to the provenance for when they try to sell the things. And there's no other vehicle to do that right now," he added.

"I told my friend, Bill Sear, give me all your World Tour stuff and I'll put it in an exhibit for six months. So instead of constantly just buying, I can go at this another way. I can just go around to the collectors I know (many of whom were included in Wong's incredible book), like a curator would. I can just borrow stuff, and it would be a wonderful showcase for the hobby."

It's virtually impossible to get Cypres to engage in anything approaching braggadocio, but he will grudgingly concede that the exuberant response from the hobby's elite that Thursday evening was gratifying (my words, not his).

"All the dealers know what I have, and I have been buying for years, but I don't think anybody expected to see what they saw, judging from what they told me.

"I think nobody ever expects to do what I did. They knew I had stuff, but they didn't know how I would present it how it would look."

That's one of the aspects that so clearly is a point of pride: the way he so elegantly portrayed these treasures from his collection. "It was satisfying to me that they liked the presentation as much as the stuff. The stuff is the stuff. I didn't create the Ruth uniform from the 1934 World Tour. That's just there and I bought it. There is no artistic expression in buying something," he added.

"I never had any training, or history in displaying stuff. So said, 'Let me try it. I'll put it up on the wall and see what happens.'

"And the real interesting thing is to see whether people will look at it as an artistic thing. And when people say, 'Boy, the presentation is great,' that's as important to me as when they tell me I have wonderful pieces, because the presentation makes a piece better.

"The nice thing from what I heard is that people enjoyed it not just from the quality and scope of the material but from the way it was presented," Cypres continued. "The colors, the life, the brightness and the visual effect. A lot of people said it was more fun than going to the Hall of Fame. They would relate to it more."

I would put it differently than that. For me - and nobody takes more delight in the Hall of Fame and the Village of Cooperstown than I do - the difference is that there are more spots at the Hall that I can quickly glide by or even pass over completely, whereas just about every room and Cypres' museum would stop me dead in my tracks. You truly would need hours to get a feel for the museum.

That "feel" is clearly something that was of paramount importance to Cypres when he conceived the idea and when he actually executed it. "What I think is the difference, when you look at baseball cards, there's a personal identification for people, because they remember having cards. And the Hall of Fame doesn't have that.

"When you look at movie posters, people say, 'I remember that movie.' And people relate to that kind of thing," Cypres continued.

And he notes that in some cases they even remember the poster itself and that there's more of a sense of personal identification with the stuff that he has, because the Hall has things that people basically look at from afar.

"I tried to create something that I thought people would like to come in and see. A museum should be attractive to people, all kinds of people.

"So I still have that question in my mind, 'Will people come to see my museum?' "

You heard it here first: He built it, and they will come.