News

A funny thing happened during Jeff Bagwell’s journey to Fenway Park

By Robert Grayson

As a youngster growing up in Connecticut in the 1970s, Jeff Bagwell envisioned himself playing Major League Baseball in Fenway Park, as a member of his beloved Boston Red Sox. It’s the stuff dreams are made of.

Jeff and his entire family were avid Bosox fans. His grandparents were part of Red Sox Nation. His mother, Jan, went to Red Sox games for decades. And his father, Robert, was a huge Ted Williams fan. As an adult, Bagwell’s dad got the chance to meet and talk with the “Splendid Splinter”—a tremendous thrill.

Jeff’s idol was—no, make that, is—former Red Sox left fielder Carl Yastrzemski. How could you be born in Boston, as Bagwell was in 1968, and grow up in Killingworth, Connecticut, a suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, in the heart of Red Sox country, and not be a Yaz fan?

“Everything in my house was about the Boston Red Sox. And when the Red Sox played the Yankees, well, that rivalry was what baseball was all about in my house,” the new Baseball Hall of Famer recalls.

Though players have little control over where they end up if they follow their dream and try to make it in pro baseball, Bagwell was pushing as hard as he could to chart a course to Fenway Park. And things were going well for him. He was an outstanding athlete at Xavier High School in Middletown, Connecticut, where he turned heads as a shortstop on the school’s baseball team. He was also an exceptional high school basketball player and set goal-scoring records in soccer.

He opted to stay in New England after high school, accepting a baseball scholarship to the University of Hartford. In college, Bagwell shifted from shortstop to third base, a change that suited him well. He both flashed the leather and showcased his batting prowess for the University of Hartford Hawks. With a college career batting average of .413, the impressive right-handed hitter attracted some interest from the pros.

Then the dream came true! The Boston Red Sox drafted Bagwell in the fourth round of the 1989 Major League Baseball draft. The third baseman split his first year in the Red Sox organization between Rookie and A ball. Then it was on to Double-A in 1990 and a stint with the New Britain Rock Cats in the Eastern League.

New Britain, Connecticut is right smack in the middle of Red Sox territory. With a .333 batting average, Bagwell easily locked up the Eastern League’s Most Valuable Player award in 1990 and he could see Fenway Park in his future. The 22-year-old third baseman was one of the Red Sox’s hottest prospects.

But this isn’t a fairy tale, and in real life the unexpected happens. Despite his best efforts, Bagwell was sidetracked on the road to Fenway. On Aug. 31, 1990, at the end of the Rock Cats’ season, the Red Sox, battling it out in the American League East and in dire need of bullpen help, reached down into their minor league system and traded Bagwell to the Houston Astros for right-handed reliever Larry Andersen.

“What! I mean I couldn’t believe it. I thought the guys were joking around with me,” Bagwell says. “But it was true.”

The entire Bagwell clan took the news hard.

“I was playing for New Britain and I figured I’m supposed to go to Pawtucket (the Red Sox Triple-A team), then on to the big leagues. When they heard the news, my grandmother was crying, my father was crying, my mother was crying, everybody was crying,” Bagwell remembers. “I’m a kid from Connecticut and I hear Houston. I’m thinking, ‘What’s that about—tumbleweed and horses?’ But, of course, that’s not what Houston is about.”

And so, in the blink of an eye a childhood fantasy was dashed. Or was it?

“At the time, being called up to the Red Sox, if that had happened, would have been the ultimate dream come true,” Bagwell says with a wistful smile. “Just playing for the Red Sox would have been enough, I thought.”

He never dared to take the dream a bit further and think that a career in Major League Baseball could end with a plaque in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

“So, that wasn’t even part of the dream. I mean that’s where Ted Williams and Carl Yastrzemski wind up (the Hall of Fame). It’s just crazy for me to think about being in that group. It’s unbelievable to me,” says the four-time All-Star (1994, 1996, 1997 and 1999).

But Bagwell joined them this year after being voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

“It’s surreal. I’m very excited and happy, but it’s surreal,” he said.

Bagwell admits that he was “the saddest guy around” when he heard about being traded to Houston. But he quickly adds, “It was the best thing that ever happened to me in baseball.” It worked out pretty well for the Astros, too, as Bagwell became one of the franchise’s greatest players.

Butch Hobson, the manager of the Rock Cats, helped Bagwell put the trade in perspective.

“He (Hobson) was mad when he first got the news that I had been traded,” Baggy recalls. “We had three games to go and needed one win to make it to the playoffs. But I couldn’t be in the lineup. I was traded. I was off the team.

“When he calmed down, he said to me, ‘Y’know, this might not be a bad thing for you. You’ll get a chance over there—a real chance.’”

At the time, Wade Boggs was playing third base for the Red Sox. Tim Naehring, a third baseman on the rise, was also on the team. And Scott Cooper, another top-notch third base prospect, was holding down the hot corner at Pawtucket. So, with Hobson’s words in mind, the dream—at least of playing Major League Baseball—was slowly beginning to take on new life for Bagwell.

By the time spring training rolled around in February 1991, Bagwell was focused on playing for his new team in the Lone Star State. But there was one more obstacle to overcome. The ’Stros had Ken Caminiti playing third base and Houston general manager Bill Wood asked Bagwell to move across the diamond to first base.

“To me it was always about what was good for the team, so I made the move,” says Bagwell, who played 15 years with the Astros (1991–2005).

The lifetime .297 hitter made the switch to first base look easy, but it wasn’t. He credits Art Howe the Astros’ manager at the time, and well-respected ’Stros coach Matt Galante with helping him make the transition. Galante worked with him “tirelessly” to master the position.

Bagwell explains that at third base, most of the plays were to his left side, his glove hand, because he’s right-handed. But at first base it was just the opposite: Many plays came to his right side, meaning he had to glove the ball backhanded. The newly minted first baseman was having trouble with that.

One day during the 1991 season, the Astros were playing the Cardinals. Legendary Cardinals Gold Glove shortstop Ozzie Smith was on first base when Houston decided to make a pitching change.

“He (Smith) asked me how things were going, and I told him I was having problems with my backhand,” Bagwell remembers. “So during the pitching change he literally is showing me what I have to do. He said, ‘You can’t field the ball deep. You have to get out in front of it.’ And he was showing me. I was getting a fielding lesson from Ozzie Smith during a pitching change. That’s pretty cool. You can’t get better instruction than that.”

All the hard work paid off when Bagwell won a Gold Glove for his play at first base in 1994.

One of Bagwell’s biggest contributions, however, often goes unnoticed when discussing his career. The six-foot-tall first baseman caught everything thrown in his vicinity by his fellow infielders, making Houston’s infield defense extremely potent.

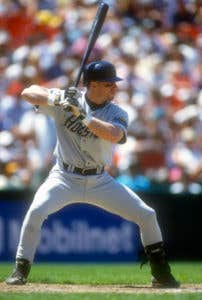

On offense, few major leaguers ever had a batting stance as strange-looking as Bagwell’s. He spread out in the batter’s box and squatted down in an exaggerated crouch as if he were sitting on a stool. Then he leaned back before swinging. The Astros superstar appeared to be very uncomfortable at the plate, but his 2,314 hits certainly proved otherwise.

When Bags came to his first spring training with the Astros in 1991, his distinctive batting stance left some Houston coaches scratching their heads. They were convinced he couldn’t hit that way in the major leagues. Once again coach Matt Galante came to the youngster’s aid, saying, “He looks like a pretty good hitter. Let him go that way,” Bagwell recalls.

That stance, which has become very recognizable to the Astros faithful, was not always part of Bagwell’s game.

“I tried hitting like Carl Yastrzemski. Then I tried to emulate Don Mattingly. I watched Tony Gwynn—he was spread out—and the stance just evolved. I don’t know where the stance I finally ended up with came from. If you figure it out, let me know. I just kept tinkering with it,” he says.

He kept adjusting his stance until one day Tony Gwynn himself told Bagwell not to move his head when he’s batting: “Once you find a stance that works, don’t mess with it,” Bags recalls Gwynn telling him. “His reason was that if you keep changing things in your stance, you don’t remember what worked. You don’t know what to go back to when you’re not hitting.”

Bagwell still seems as though he’d like to make a few adjustments in his stance.

“Yeah, I mess with it even now. Don’t teach your kids to be that way,” he muses.

In the minor leagues Bagwell never hit for power but Rudy Jaramillo, the Astros batting coach in 1991, helped the team’s new first baseman change all that.

“He (Jaramillo) told me I could hit home runs, but I didn’t believe him at first,” Bagwell says. “Rudy helped me shift my hands a little bit and taught me to hit the pitch with backspin, giving it a soaring trajectory, rather than diving down.”

Add to that Bagwell’s discipline at the plate, which enabled him to wait for a pitch he could drive, rather than swinging at anything in the strike zone, and the result was 449 major league home runs in his MLB career.

His first nine years in the bigs were spent at the Astrodome, which was not a hitter-friendly ballpark. Nevertheless, in those nine years (1991–1999) Bagwell hit .303, managing to find gaps to send the ball when he didn’t hit it out of the park.

During his 15-year career, the powerful first baseman hit 488 doubles. Though Houston was a subpar team when he first got there in 1991, Bagwell had an excellent rookie season, batting .294 with 15 homers, 26 doubles and 82 RBI on the way to winning National League Rookie of the Year honors.

He also met and became friendly with another up-and-coming Astro—Craig Biggio. Biggio broke into the Astros lineup midway through the 1988 season. By the mid-1990s, Bagwell and Biggio were being referred to as the “Killer B’s,” and both are now in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Biggio was inducted in 2015.

In 1994, Bagwell had a dream season, even though it was shortened by a players’ strike. His .368 batting average, 116 RBI and 39 home runs in the 110 games played during that abbreviated season won him the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award.

“That season (1994) was just a ridiculous season for me. When I got the pitch I was looking for, I hit it well, couldn’t miss. You’d like that to happen your whole career,” notes Bagwell.

By 1995, Bagwell and Biggio were joined in the Houston lineup by other players who had last names that started with the letter B and swung productive bats. Now, the “Killer B’s” included outfielder Derek Bell (1995–1999) and third baseman Sean Berry (1996–1998). Later on, between 1999 and 2005, outfielder Lance Berkman became an integral part of the “Killer B’s.” Carlos Beltran was considered a “Killer B” when he played for Houston from late June 2004 to the end of that season.

From 1997 to 2001, led by the tandem of Bagwell and Biggio and their swarm of “Killer B’s,” the Astros won the National League Central Division four out of the five years, missing out only in 2000. But each time they won the NL Central, they lost the National League Division Series, quashing their World Series hopes.

By the end of the 2001 season, Bagwell started developing an arthritic condition in his right shoulder. He was also having problems with his left shoulder that required surgery that off-season. But it was the right shoulder that started slowing him down. From 2002 to 2004, Bagwell played in pain but still put up the numbers to help the team win, hitting 97 home runs during that period and collecting 287 RBI. Still, it wasn’t only big numbers that impressed Bagwell.

“It’s the little things that guys do that make the team better. The sac flies, stolen bases, a ground ball to short that scores a run. A big part of our team was appreciating what other players did to make you and the team better,” says Bags, now 49 years old.

In 2004, the Astros finished second in the National League Central Division, but it was good enough to snare the NL Wild Card. In the 2004 National League Division Series, Houston defeated the Atlanta Braves 3 games to 2 and finally moved onto the National League Championship Series. But the ’Stros lost a tough seven-game series to the St. Louis Cardinals 4 games to 3.

In 2005, the Houston Astros finally made it to the World Series, but Bagwell’s degenerating shoulder condition sidelined him most of the season. Nevertheless the three-time Silver Slugger winner (1994, 1997, 1999) pushed through the pain to help the team down the stretch of the 2005 season. Helped by Bagwell’s drive and determination, Houston made it into the World Series. The Astros lost the 2005 World Series in four straight games to the Chicago White Sox.

But the games were close, and could have gone either way. Game 4 was scoreless for seven innings and Houston ended up losing 1–0.

“The World Series was one of my biggest memories for the city, not so much for me because I was hurt and I mostly pinch-hit and was the DH, and that was kind of weird. But for the city and the team it was a great moment,” the Astros star says. “For me, the thing I’m most proud of is my relationships with my teammates. Just how we interacted with each other. I made some great friends, lifelong friends.”

Robert Grayson is a freelance contributor to SCD. He can be reached at graydrew18@aol.com.