Lou Gehrig

Exhibit Supply Company ends its reign in 1980s

By George Vrechek

Following Meyer’s death in 1948, Exhibit Supply Company (ESCO) remained viable under the direction of other managers including Joseph Batten, H.T. Ames, Ford Sebastian, Sam Lewis and Chet Gore. ESCO employed 285 people in 1953. This period also included the heyday of baseball exhibit card production.

Catalogs have referred to the exhibit cards from this era as the 1947 to 1966 issues with the implication that sets of 32 or 64 cards were issued each year resulting in about 465 cards including variations. ESCO did produce dated catalogs for vendors listing the sets available which probably helped create the notion that there were annual baseball card sets.

ESCO card printing procedures

Plant manager Chet Gore had been with the company since 1937 (a year when Meyer reported a salary of $25,000 and his plant manager was paid $26,000). There was no indication that procedures for producing cards had changed drastically. ESCO needed to supply their vendors and produce new product. There was likely no timetable for when that might happen. Whenever baseball cards needed to be produced for inventory, or whenever a large new order would come in, Gore would crank out some more cards, according to Paul Marchant, who purchased ESCO in 1979.

There was no such thing as an eagerly anticipated annual issue of exhibit cards. While it may have been logical to print new baseball cards in the spring before the summer arcade season, such timing may have been coincidental. They may have printed cards once or twice a year or once or twice every several years.

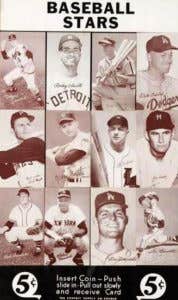

Arcade operators would order American or National League player exhibit cards as needed in bricks of 500 or 1,000. Given that there were 32 cards on a sheet, I will guess that a brick of 1,000 cards likely contained 1,024 cards: 32 cards from 32 sheets. Why horse around with dividing up a sheet?

It appears that National and American Leaguers were printed on separate 32-card sheets for most, but not all years. If you had an arcade in Cleveland or Detroit, you could order just American League cards. Except for 1962 and 1963 the backs were blank. Why should they worry about what year the cards were printed?

Players were added or deleted, team insignias were updated with in-house airbrushing and different poses might be added. However, different poses meant paying for photography again and might even trigger a player wanting to get paid, so such changes were minimal.

Changes to printing notations

In addition to updating the player images, they would also change the size, font, and location of information printed at the bottom of a card. “An Exhibit Card,” “Made in U.S.A.” and “Printed in U.S.A.” came, went and moved around between 1947 and 1961. The length of the type for “Made in U.S.A.” would vary from ½ inch to ¾ inch.

Doby’s and Rizzuto’s cards even had “An Exhibit Card” scratched off.

All of these minor notation changes were usually only on the new cards added while returning player cards retained whatever format they previously had. They were printed again on sheets of 32 with no consistent format among the cards on the same sheet.

Collectors have scrutinized the dates of player trades and retirements to think in terms of sets by year, but it is more likely that players on a sheet were never entirely up to date. It wasn’t vital. What was important was to periodically add some new look through colors, cropping or new players.

The ageless Splendid Splinter

Ted Williams’ card illustrates what likely happened. Williams’ card (without the 9) was probably printed for the first time in 1946 and, consistent with other cards, contained a salutation: “Sincerely yours, Ted Williams.” The lower right corner included “Made in U.S.A.” Williams’ image remained unaltered through 1961 even after he retired.

Williams’ pre-1946 picture is found on an uncut sheet next to a 1960 image of Rocky Colavito (Detroit uniform) along with an airbrushed pre-1953 image of Earl Torgeson. Williams never aged. His image, including the salutation, would be dropped in and printed with other players in the 1950s with no such salutation. As with the cards of other players, the “Made in U.S.A.” got replaced in the late 1950s by “Printed in U.S.A.” on Williams’ card. Even Mickey Mantle had only three different poses on ESCO cards over his career.

Special issues

There were special issues for Baseball’s Great Hall of Fame (1948), Wrigley Field (1961) and Dad’s Cookies (1959). In 1955, 64 backs were printed with a postcard format. Sixty football cards were produced between 1948 and 1952 with typical changes each time they were printed, plus some players were included in a Sports Champions set. Cards were printed in black and white, sepia (brown) or other hues within the same era.

Prices for 1,000 cards were $3.85 in 1949 and still only $5 by 1961. It wasn’t until 1996 that Topps beat ESCO’s record for the number of years of issuing baseball cards.

Gore takes over in 1957

Chet Gore became president in 1957 and by 1960 took over ESCO (minus the switch business) and moved the company into much smaller quarters at 4719-21 W. Lake Street in Chicago. The arcade amusement business was fading; however, Gore still had some arcade customers and produced cards as needed.

In 1962 statistics were printed on the backs of the cards in red or black; in 1963 the stats were only in red. From 1964 to 1966, the backs were blank again and production was reduced. A set of recording artists was printed with bios on the backs. ESCO employed 15 people in 1965. Based on a 1961 ESCO brochure, only three of their 44-card sets were sports figures (baseball players, boxers and wrestlers); nine were art model cards. Brigitte Bardot was their featured card photo. Only six of the sets indicated that they had been revised for 1961. In 1964, a big seller, according to Gore, was a 25-cent postcard of Pope Paul VI.

I remember collector Bob Solon (1923-2009) telling me that he would visit ESCO and buy cards directly. In 1966, Solon learned that Topps forced ESCO to delete six players: Hank Aaron, Eddie Matthews, Warren Spahn, Dick Groat, Don Drysdale and Rocky Colavito. The cards had already been printed and Solon wound up with a few of the cards that were pulled. Gore may have decided after 1966 that it wasn’t worth the hassle to print any cards of players who were under exclusive licenses with Topps.

Still producing cards after 1966

In 1968 ESCO switched their card stock from the normal grayish-cream color to white for any subsequent issues, which included movie stars, beach bunnies, automobiles and TV stars. They also issued 24 new Hall of Fame cards of retired players in 1974 and 64 cards in 1977 using the white stock. It is quite possible that the company also reprinted other baseball and arcade cards on white stock after 1968. Exhibit cards with 1927 copyright dates have been found with white backs. The originals are still inexpensive. Why would someone counterfeit cheap cards? It is likely that ESCO printed these cards after 1968 without changing anything else to fill orders for old customers.

The cards changed to suit the times, but eventually time ran out for the arcade card vending machines.

Marchant buys what’s left

Paul Marchant of Charleston, Illinois, was a teacher in the late 1970s and decided to turn his sideline of card dealing into a full-time occupation. He opened three card stores. Like Bob Solon, Marchant visited ESCO to buy exhibit sports cards in bricks of 500. Marchant stayed in touch and was there when Gore and two minority shareholders, decided to sell the company in 1979.

I asked Marchant what he remembered from his experience. Marchant recalled, “Chester Gore made changes at random with no pattern. In the exhibit file there were a few uncut paper (proof?) sheets of sports cards where he had X’d out a few cards and wrote in names of new players he wanted to use. There were only three or four of these in total. Going back to pre-1960 when Exhibit was much larger and more important, I guess it is possible that there may have been yearly adjustments, but I have seen nothing about that in any of the files I have been through. That being said I have not gone through all of the files completely.

“Also what he (Gore) did was print cards when inventory ran low on all of his products. When I was negotiating with him, I know he printed a few titles because Disneyland or some other customer had ordered them. It is my feeling that he ran short print runs quite often on some of his better selling items. On a lot of his products such as fortune telling, horoscope, etc. he was still using the plates from the 1920s with no change.”

Marchant’s exhibits

Marchant (33 years old at the time) agreed to buy everything including arcade machines, plant equipment, presses, cutters, parts, photos and records. Marchant came with his dad and a truck to clean out the plant. His dad helped him convert some of the arcade machines to accept quarters rather than nickels, and he was able to sell the 100 arcade machines. The miscellaneous parts and plant machines were sold, and Marchant was left with over 7,000 photos that had been used to produce arcade cards of all kinds.

Marchant used a few photos to have baseball cards printed and issued two, 32-card sets on both white and on brownish cardboard (printer’s error on the HOF set) with notations “Exhibit card 1980.” He added different photos of Roger Maris, Stan Musial and Lou Gehrig to the ESCO photos in order to create the sets. Marchant then decided to stop creating sets and sold most of the ESCO photos. Gore retired and retained some exhibit cards for his own collection. Exhibit Supply Company’s corporate entity was dissolved by Marchant in 1985.

Exhibit cards that aren’t

Cards have been found that were likely reprinted by others after 1980 on dark cardboard with muted coloring or on even whiter cardboard than ESCO used with no notations. Several such reprints included New York teams. White-backed baseball exhibit cards using the ESCO photos can be found today in arcade machines at the Musée Mécanique, San Francisco’s Antique Penny Arcade, but bring four quarters for a card instead of a penny. Vintage arcade machines are also collectable, but take up a lot more room than the cards.

The many post-1966 baseball exhibit creations have confused purchasers, especially if you are just looking at a photograph of the card. It helps to have the card in hand to know if you are getting a cheaply produced reprint from unknown origin, an ESCO reprint of an older issue or a cheaply produced original from ESCO’s vintage years. The good news is that most of the vintage exhibit cards are still reasonably priced.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to Sports Collectors Digest and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.