Joe DiMaggio

A look back helps understand Exhibit Supply cards

By George Vrechek

J. (John) Frank Meyer was born in Peoria, Illinois, in 1881. He came to Chicago with a fifth grade education, but by 1907 headed a company that became a leader in its industry, employing some 285 people at one time in its Chicago plant.

His company was Exhibit Supply Company, and among its products were arcade cards of sports figures. Meyer would be amused to find that his cards, which he sold profitably for ½ cent each, are still scrutinized by collectors today and purchased at considerable expense.

Amusement park arcade memories

As a kid in the 1950s, I bought exhibit cards from arcade vending machines at Riverview, a Chicago amusement park. The cards didn’t have any numbers, the backs were blank and the cards didn’t fit nicely into the shoe boxes with the regular cards. To make my exhibits to blend a little better, I cut some of them down to the size of the Topps cards.

I have since found exhibits from the 1940s cut by young collectors to match the size of the 1948 Leafs. It was nice to have at least one card of Stan Musial and Joe DiMaggio, but most of the exhibit players were not in their current uniforms, the photos looked old and the colors were pretty well limited to one. I viewed them as “fillers.”

Of course, what was of marginal interest in the 1950s can become the holy grail today.

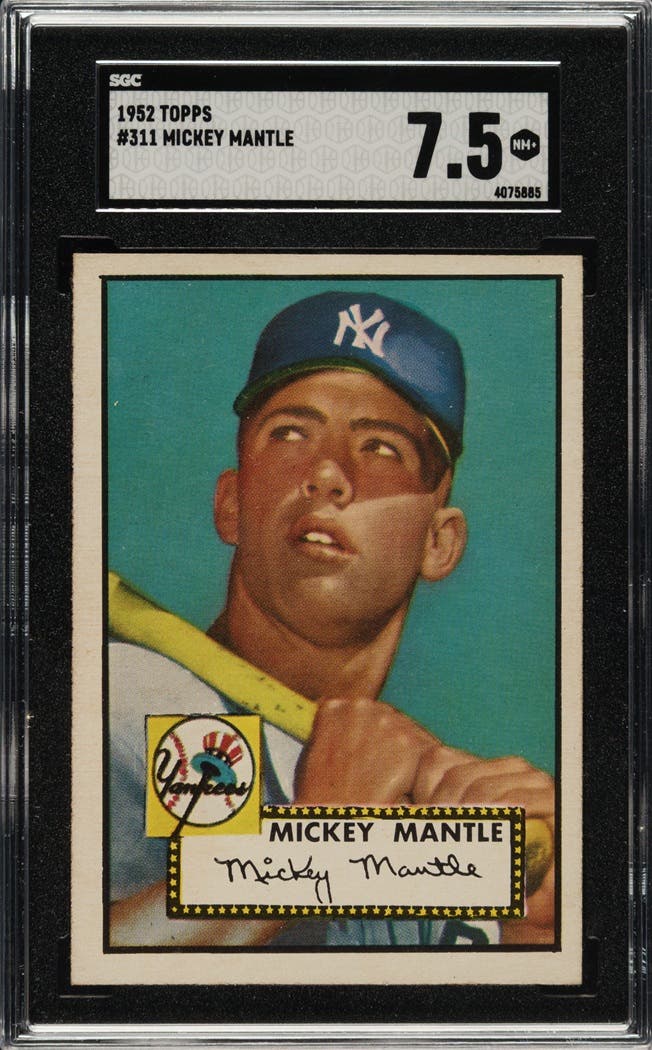

We slab the cards, check out the variations, look for centering and clarity and successfully turn what was a penny card into a several hundred dollar object of affection. However, collectors have had fun trying to make sense out of the exhibit card puzzle.

Who issued the sets, what cards make up a set, when were sets issued, and what are the variations? Our penchant for orderliness is disturbed because exhibit cards don’t lend themselves to easy organization.

Let’s see if we can look back at the history of the company that produced most of those cards, the Exhibit Supply Company, and put things into a perspective that will help us understand why the cards have always been puzzling.

Meyer starts in Chicago as a printer

Meyer came to Chicago and got into the printing business. By the early 1900s his Meyer Printing Company had an office in the Pontiac Building at 542 South Dearborn Street, in what was referred to as Printers’ Row. By 1910 he controlled a small partnership involved in the amusement arcade business called Exhibit Supply Company (ESCO, established 1901), which Meyer had joined in 1907.

Meyer heads Exhibit Supply

Meyer began combining his printing knowledge with the needs of the arcade business. One of his early products was a coin-operated machine that produced metal ribbons stamped with whatever information you wanted to type.

Within a few years, they were producing machines that would vend postcards, horoscopes or photos of young women described as “art models.” After WWI business boomed.

The Billboard trade journal reported, “Virtually overnight Exhibit Supply, aided by Meyer’s creative capacities, became a major manufacturer of arcade and amusement game lines.”

Meyer was living in downtown Chicago with his wife, Elizabeth, his two young daughters, Helen and Oraline “Brennie,” his brother (Clare) and his mother. His wife had been born in Switzerland as had his own father. He was a hard worker with a family to support, always looking for new products.

He became a director of the Chicago Motor Club and was a Mason and a Shriner. Otherwise he seemed to keep a pretty low profile as to ads, publicity or even phone book listings. I found his name in a 1914 Chicago directory listed as a printer. In a 1917 directory his description was slot machine dealer, and by 1923 he was an amusement machine dealer.

His statements in company sales literature gave no hint of a fifth grade education. He projected quality products, sensible procedures and an enthusiasm for his customers’ profitability. He may have overstated a few things, but it all sounded pretty good.

The amusement industry dealt with nickels and pennies and needed to continually adjust to wrestle those hard earned pennies from the customers (referred to as “players”) through good and bad economic conditions. Meyer’s business evolved into developing and selling arcade machines, providing parts and selling cards and premiums to use in the machines. His staff was charged with coming up with new, affordable products that would attract customers.

The ever-evolving arcades were sources of entertainment for the masses in those days with short movies, music, games of chance, digger machines, peep shows and card vending machines. ESCO created and patented many such machines. The cards coming out of vending machines were a small portion of the arcade business, but proved to be more lasting investments than other elements.

Cranking out cheap thrills every 30 days

By the 1920s ESCO needed cards of baseball players, boxers, movie stars and more art models to fill those machines. Meyer promised arcade operators: “We release a new series of cards every 30 days.”

I found no evidence that Meyer was a sports fan. He seemed to be a fan of whatever his customers wanted and the law would permit.

ESCO’s brochure explained, “Our latest Art Model stereo views never fail to get top money when shown. Every set of views we publish are passed by the New York censors.”

Indeed, the marginally risqué cards might sell in arcades for 5 cents versus a penny for baseball players. Maybe the penny baseball players were used by youngsters to conceal the nickel art models that were the most profitable cards in these arcades?

ESCO would buy photos (from their “Hollywood studios” of the “most beautiful subjects”), but they had to produce cards that could be sold cheaply, and they had competitors. There wasn’t much margin for paying for royalties, publication fees, complicated layouts, two-sided printing, real autographs, written descriptions or quality paper. While they would add some new cards to a printing, they would often just change a few cards or update a few photos and crank out more cards in bricks of 1,000, which sold to vendors for $3.85. There you go; a new set every 30 days.

Machines needed cards that fit

Exhibit card enthusiast Adam Warshaw makes the point that if you had a machine purchased from ESCO, you needed to use cards that would work in the machine, which was supplied by only ESCO. The cards had to be the right size and thickness. Machines dispensed two series of cards side by side with about 1,200 cards already in a machine when delivered.

ESCO’s plant

To handle the growing business, which combined manufacturing, printing, creative and sales operations, Meyer moved into a large plant at 4222 W. Lake Street in Chicago around 1924, in the middle of what was a vibrant manufacturing corridor along the Lake Street elevated line. His home was now nearby at 240 N. Parkside Avenue.

He brought his brother Clare into the business as “chief experimental engineer” and gradually added key employees: arcade sales manager Perc Smith, general sales manager John Chrest, plant manager Chet Gore and son-in-law Stuart Knabe. Meyer had been the sole owner of ESCO for many years but finally incorporated in 1935 and started including others as shareholders.

Sports cards

ESCO started producing boxing and baseball cards in 1921, adding more sports-related cards and kept at it for another 58 years issuing cards of football players, boxers, wrestlers, sports champions, as well as movie stars, art models, radio stars, TV stars, cowboys, Indians, automobiles, planes, fortunes, love letters and other subjects.

The vast majority of exhibits were not sports cards.

ESCO usually copyrighted what they could, which meant joke cards, fortunes and cartoons, but not photos of famous people. The copyright usually, but not always, included the date; thus it is easier to date some of the non-sports cards.

Baseball exhibits were of single players from 1921 to 1928. By 1929 ESCO went to the four players on one card format. However, by 1939 they were back to one player per card and generally printing 32 cards at a time.

Approximately 76 cards of different players were pictured between 1939 and 1947, which included “salutations” and signatures (by ESCO artists).

Return to single player cards resulted in short prints

The switch back to one player per card resulted in some “short prints.” In order to update the set, players would get dropped from subsequent printings like the elusive Mike Kreevich, Hugh Mulcahy or Johnny Rizzo. Had the company been continuously running cards of single players in the 1930s, these players would have been printed in prior years.

During the 1950s Hegan, Goodman, Williams, Wertz and Hodges were easy to find. They were printed about every year with few changes. The same thing happened at the end of the exhibit card run when Yastrzemski, Kranepool and others were added only in the final years and are now hard to find.

Cutting and cropping

There are many slight differences on cards of the same player but surprisingly, given the economical production, there are few cards that are obvious miscuts. ESCO usually had a white border between groupings of four cards on a sheet of 32. The 32-card sheets must have been carefully cut along the white guidelines and then the four-card sheets were cut.

However ESCO did it, miscuts were rare. The slight cropping differences are more likely the result of using the same photos to re-run cards but with slightly different alignments.

Changes in the 1940s

When World War II arrived, ESCO directed virtually all its efforts to war production, although arcade cards still went out the door, including cards with a military theme. Meyer was personally involved in ESCO’s developing and manufacturing switches used to open bomb bay doors and release bombs. They also provided radar parts and assemblies for submarines.

Switches were still needed after the war and the switch business, carried on by their Electro-Snap Division, became more significant to the company than the amusement arcade business, which resumed after the war.

The plant was bustling and in 1948 they built an adjoining one-story addition to double the production area.

However, 1948 was not a good year for key managers of ESCO. Meyer suffered from a heart ailment and had moved to Pasadena, California, keeping in touch with the business by phone. He also remarried a woman by the name of Hazel Spencer Meyer. In November 1948 Meyer died at the age of 67. Sales managers Perc Smith and John Chrest both died in June 1948.

Part 2 of this article will cover ESCO’s history from 1949 to 1980.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to Sports Collectors Digest and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.