News

Classic Card Sets: 1966 Topps Baseball

Underrated and Underloved

By T.S. O'Connell

I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to suggest that the 1966 Topps set is one of the more underrated – maybe even under-loved – offerings from the card company through that decade. Call it the middle child, forgotten and maybe even a bit forlorn, flanked by an elegant and more popular 1965 issue that quite naturally commands greater respect in the hobby and a younger sibling from 1967 that seemingly doesn’t have to work as hard to accomplish virtually the same thing.

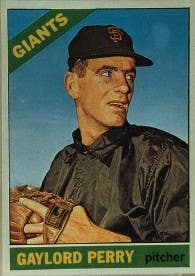

I don’t know if that makes it the Jan Brady of vintage baseball cards, but it is interesting that an issue with arguably the most technically distinctive photography of the era – in terms of good, sharp, perfectly focused images – winds up being so rudely dismissed by so many. Hell, I can’t even exempt myself from the underlying accusation, since I’ve never collected the set, not contemporaneously in 1966 or even decades later in the hobby, though I managed to put together complete sets of just about everybody else in our metaphorical family.

But I can take some comfort in knowing that I’m hardly alone in my ambivalence, confused though it may be. “It’s an incredibly boring set,” is the way Rich Gove of Rich Gove Collectibles less-than-delicately describes it. Gove, who routinely carries an inventory of top-condition vintage Topps and Bowman cards, concedes that his relative disdain is purely visceral, and he has no compunction about trafficking in the 1966 pasteboards when they come along.

“There’s a lot of interest in the high numbers,” Gove said, but he also pointed out that he doesn’t even get offered as much 1966 Topps as he might have otherwise expected, though he did have some unopened packs at one time many years ago.

The observation about the high numbers is pretty standard: fellow veteran dealer Irv Lerner calls them “super scarce,” and this from a man who has been traveling the card show circuit from the days long before it could even be called that. One aspect that ought to add to the mystique of 1966 Topps is the semi-highs, the cards from Nos. 447-522 that are thought to be nearly as tough as the last grouping from Nos. 523-598.

So, we have super photography, difficult semi and high numbers and an issue that neatly encapsulates nearly three decades of baseball history with a checklist that features most of the great stars of the 1950s and 1960s, plus wonderful portrait glimpses of many of the top players from a decade earlier, now in the managerial ranks. What’s not to like?

The issue has a kind of ho-hum rookie class, if that’s a concern for collectors, though one suspects that such damning with faint praise seldom impacts a decision about whether to pursue a particular issue. Besides, the Jim Palmer rookie card is a tough one to find in top grades; others include Ferguson Jenkins and Don Sutton, and a couple of Yankees, Bobby Murcer and Horace Clarke.

Those last two fellers raise an interesting question. Is the seeming lethargy surrounding the 1966 Topps set due to the transformative quality of the baseball season itself that year? The Murcer rookie card is listed in the December issue of Tuff Stuff’s Sports Collectors Monthly at $30, while Clarke shows up at $45. The price of both players is reflective of the inordinately powerful impact Yankees cards have in the hobby, but for the latter to be 50 percent more expensive than Murcer is startling. Maybe it’s because they ended up naming an entire era after Clarke, ie. the period in which the American League adjusted to having a more conventional style pennant race every year rather than just having the Seven Dwarfs gobble up the Yankees’ table scraps in an offseason.

After having won 14 pennants in 16 seasons from 1949-64, the Yankees would not win another until 1976, though it’s doubtful anybody would have been able to foresee that in 1966. Still, the traumatic nature of the Yankees’ fall from grace in 1965 (the year upon which a 1966 issue would be based) seemed to be so pronounced that the Topps designers opted not to include the by-then requisite World Series subset that had been a staple of every Topps issue for the previous seven years.

Not sure if that gets charged as an error, though the World Series subset would resume promptly the following year. Speaking of errors, that quaint little aspect of hobby folderol doesn’t prove to be much of a factor in 1966: there are a handful of “Sold” or “Traded” variations that would likely be met with a collective yawn by all but the most obsessive set collectors and a Series Two checklist with either Warren Spahn or Bill Henry (correct) listed as card No. 115.

And if putting together the 598-card issue (minus variations) needs even greater enhancement, you can always rev yourself up to passionately pursue the three different versions of the buttons on Don Landrum’s pants. I gotta tell you, I never gave Landrum’s card the kind of intense scrutiny that must have been required to discern all that nuance. And there must have been something about the Cubs’ journeyman outfielder, since his 1963 Topps card has photographs of Ron Santo, rather than Landrum. Those were never corrected, so when a problem arose three years later, the Topps guys may have felt guilty and went a little crazy with “No Button, Full Button, Partial Button” mania. Me, I never noticed.

What I did/do notice about 1966 Topps is the color coding, which for once Topps managed to keep straight all the way through (I believe – If I am wrong, I know I’ll hear about it quickly). Topps had been dabbling with this idea for nearly a decade, tentatively and erratically at first, in 1958 and 1959, putting just about everybody from a team in the same color, then Bang!, they slip in a different hue for a couple of guys just to see if the youth of America were actually paying attention.

Though the design itself is no great shakes – and probably suffers in comparison with both 1965 and the more attractive 1967 issue – it work’s well enough and can hardly be the source of the hobby’s ambivalence about the set. For that we’ll have to look elsewhere.

And one of my favorite barometers for evaluating any vintage card issue – I don’t typically concern myself with such tawdry considerations as card prices – is whether any of the cards might be considered either the best or among the best for any particular player.

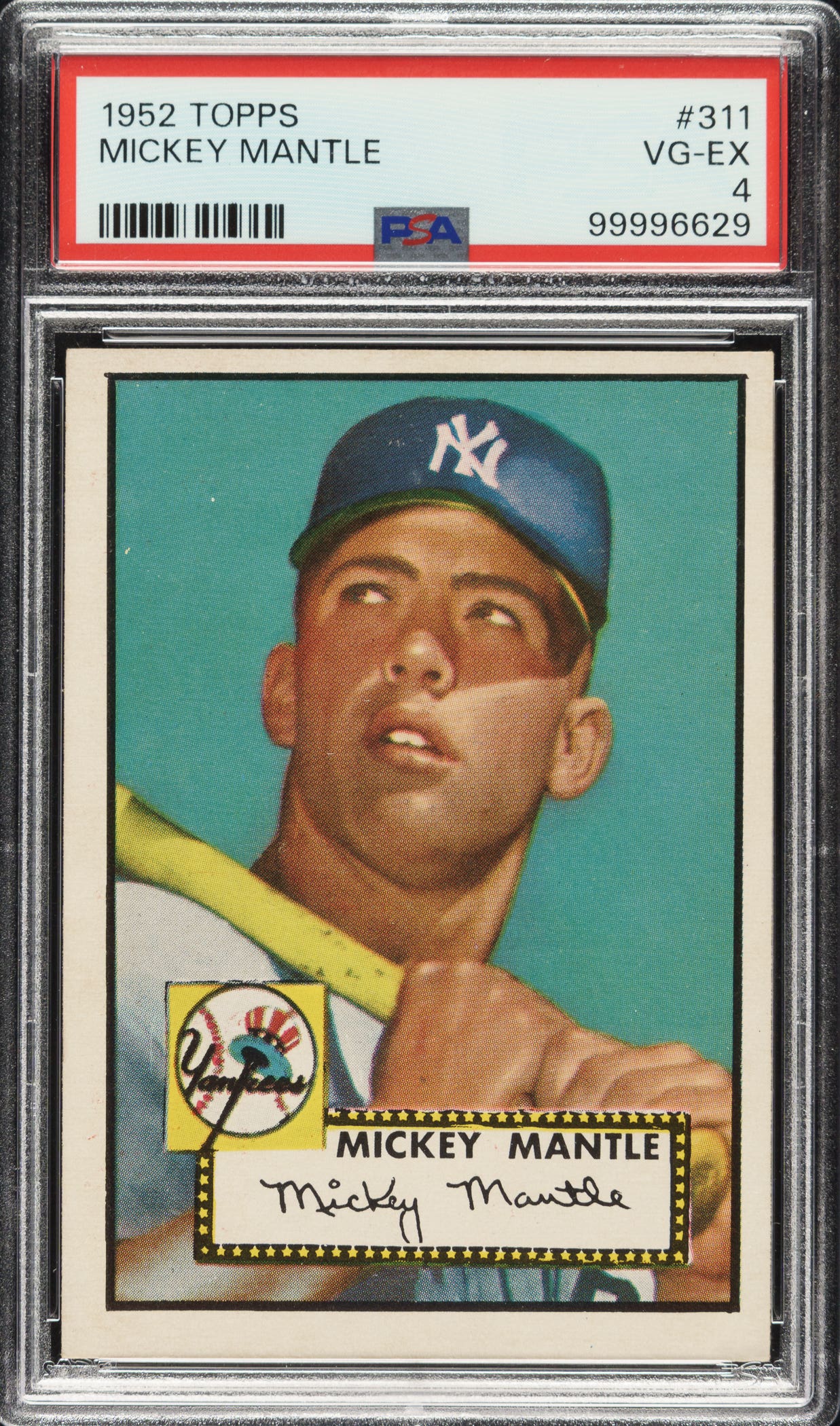

With that yardstick, 1966 does just fine, because literally dozens of the cards – mostly the posed-action ones but a number of the portraits as well – qualify nicely on that score. I submit for your consideration, No. 1 Willie Mays, No. 50 Mickey Mantle, No. 70 Carl Yastrzemski, No. 72 Tony Perez, No. 100 Sandy Koufax, No. No. 110 Ernie Banks, No. 180 Vada Pinson, No. 290 Ron Santo, No. 300 Roberto Clemente or No. 320 Bob Gibson. And that’s just a sampling.

And there’s plenty of cognitive dissonance associated with seeing legendary players in garb so disturbingly different from how they are remembered. Thus we do double-takes when we encounter things like No. 310 Frank Robinson in a green color-coded Orioles card but clearly wearing a Reds jersey, No. 386 Gil Hodges in a Washington Senators cap or No. 530 Robin Roberts as a Houston Astro. Not Topps’ fault, but eeewwww!

For a final observation, I make reference to a well-respected hobby reference work that I used for research on this article, and in the “For and Against” section it opines for 1966 Topps that “There are no apparent negative aspects to this set.”

Really? Nothing at all? Not even about 115 players appearing without caps? I saved this till last because I know I’ve commented/harped on this particularly nettlesome practice in regards to a number of 1960s Topps set, but I don’t think I can skip it entirely just because it’s getting repetitive.

Unless your contemplating working on in the costume department for a Broadway play like “Grease” or “West Side Story,” seeing all these crew cuts can serve no useful purpose that I can see. Plus, if I want to admire a receding hairline I have a mirror that works handsomely, er, effectively, for that purpose.

There are dozens that make you want to avert your eyes, but none more than the No. 130 Joe Torre, which screams pizza delivery boy rather than All-Star ballplayer and Hall of Fame manager.

Joe, like Topps itself, is Brooklyn based, so I don’t assume he would be likely to file a lawsuit over it, and obviously the statute of limitations has long since expired. But he could.

And clumsily fiddling with the headgear doesn’t help much, either. Don’t even get me started on whatever the hell Topps was trying to accomplish with another of my favorites, Eddie Mathews (No. 200).

Darn. I had thought I might go ahead and try to put this set together someday, but after writing these last two or three graphs, I’ve got myself so agitated I just don’t know.