Football

Butch Jacobs and His Work on Topps Football Cards

By George Vrechek

In a previous article, SCD spoke with retired Topps Director of Photography Butch Jacobs about the process of selecting photos for baseball cards (click here to read). We continue that thread by looking at Topps football card photos with input from Jacobs and others.

Cameras, film, lenses and printing techniques improved dramatically in the 1970s. Topps baseball cards evolved from fuzzy, distant action photos and stiff portraits to close-up game photos and candid portraits. Football cards went through similar changes; however, it turns out that changes in photography had much less of an impact on the look of the cards than did licensing agreements.

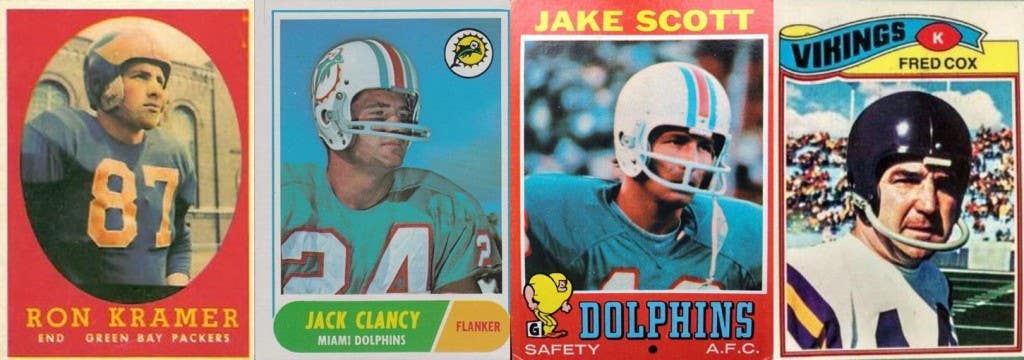

Football cards from the 1970s have that “generic look” caused by player uniforms that don’t look quite right. What doesn’t look right is a lot of airbrushing. What got airbrushed or left out of the picture and why makes for an interesting story. Let’s start at the beginning of Topps’ involvement in pro football cards.

Berger’s war stories

While Topps and Bowman were at war over the lucrative baseball card market in the early 1950s, crafty Sy Berger (1923-2014) of Topps was also looking to get Topps into the pro football card market, which was exclusively with Bowman. Berger had vied with Bowman in the contest to sign Major League Baseball players, had made inroads but had not yet controlled all the player agreements by 1955. In a 2011 interview with Berger, he told me that Bowman wondered how Topps was going to get into football cards without buying the agreements that Bowman had for football. However, Berger had become friends with NFL Commissioner Bert Bell, who shared a similar creative bent toward sports marketing. Berger told me that Bell even thought that he would be a great person to be involved with a possible NFL expansion team. Berger got a league agreement through Bell to produce pro football cards starting with the 1956 season. Berger didn’t need Bowman, although Topps bought out Bowman anyway.

The NFL Players Association was just being formed in late 1955 and was not involved in Topps’ initial deal with Bell and the NFL. The mechanics of the license are spelled out in a Federal Trade Commission action against Topps decided in 1965. Hobby writer Dave Hornish directed me to this exciting 90-page decision, which confirms that the licensing arrangement was through the NFL rather than the individual players or the players’ association. License payments went to the NFL to contribute into the players’ pension fund.

Topps veterans question licensing

Without being able to talk to Sy Berger again, it is hard to confirm exactly what happened (and when) as to football licensing agreements after 1956. Sy Berger’s daughter, Maxine Berger, retired Topps Director of Photography Butch Jacobs and retired Topps writer Len Brown all provided what they knew about the subject. Brown, who worked at Topps from 1959-2000, wrote the backs of the football cards in the early 1960s and recalled, “The logos on football was something that Sy Berger was on top of, and he worked with Ben Solomon and the art department on the legal aspects of it.”

I checked with Ira Friedman, the current vice president of licensing and publishing at Topps, who has been with the company since 1988. Friedman tried to help by putting me in touch with Arthur Shorin. Shorin is the son of Topps co-founder Joseph Shorin. He joined Topps in 1958 and served as the CEO. He was very cordial in responding; apparently his mother threw out his baseball cards as well. Shorin commented, “Sorry that I can’t help but, in fact, much of those issues were handled between Sy, my late cousin Joel, who was CEO, and lawyers who have gone to their great reward.”

Licensing of football “intellectual property” today involves dealing with the NFL Players Association (NFL Players Inc.) and the league (NFL Properties), if you want to show players in team uniforms with logos. The players and league may enter into one joint agreement with the licensees to facilitate this three-way agreement. The players get paid to appear on cards, but any logos on their uniforms are trademarked by the teams and controlled by the league for any national issues. License payments to the league get distributed evenly to the teams. Basically without having both licenses, you get a player in his underwear or a uniform on a dummy.

But in 1956, it looks like the NFL (league) was just happy that license payments were going to the players’ pension fund and probably diminishing what the teams had to contribute. Players didn’t have much bargaining power to do better. All of that was about to change, however.

Photos from camp

Butch Jacobs of Topps had the job of directing the photographers, identifying the players and picking the right photos from 1973-2007. According to Jacobs, they felt that collectors wanted to see what the players looked like. Helmets, face masks and chin straps interfered with getting a good look. Consequently, Topps photographers went to practices and took portraits of players without helmets, except for Y.A. Tittle, who apparently preferred photos of his helmet rather than his balding head. To enliven the photos, photographers would have some players doing crazy moves like flying through the air or striking the Heisman pose. None of the early photos were from game action.

Some photos involved players wearing or holding helmets. Many teams had generic-looking helmets at the time, but a few teams like the Rams and the Colts started going through the trouble of having their equipment managers maintain special helmet paint jobs. Elroy Hirsch’s 1956 card shows him flying through the air with those crazy legs avoiding imaginary tacklers while wearing his distinctive Rams helmet.

Identifying the players

As with baseball, the football photos were taken the year before the player appeared in a set. Players would quickly rotate in front of the photographer. Photographers would send Topps rolls of undeveloped film along with a player roster with numbers. Jacobs, or his predecessor Bill Haber (1942-95), would have contact prints made, identify the players and file the photos in a folder for each player by year for preparing the next football set. Haber’s predecessor must have been particularly busy handling all this for every sport since there were a few misidentified players who wound up on cards. The most glaring examples were using the wrong Jim Taylor in 1959 and 1960 and putting Don Owens on R.C. Owens’ 1958 card. Fleer and Philadelphia Gum had their share of misidentified, reversed negative and misspelled football players as well.

Backgrounds

Topps seemed to do a better job of dealing with backgrounds behind the players than did Philadelphia Gum, whose 1964 cards of Cleveland Browns were taken next to a parking lot. One solution that Topps used frequently was to put a solid colored background or a fake sky behind the player, and the Fleer photographer may have erroneously assumed that Fleer would also add a background. Joe Schmidt’s 1960 Topps card appears as if he is in front of a hill that disappears into an airbrushed haze behind his head.

Logos: A growing issue

The 1962 Topps set added black-and-white action photos along with the portraits. The action photos showed any helmet logos, as did a few of the player portraits each year. On the card boilerplate for some years, Topps included team logos that appear to have been drawn by Topps and were different from the actual team logos. These Topps-drawn logos started to morph considerably over the next few years to become intentionally more distant from the official logos, which were becoming more prevalent. Teams were finding that team apparel licensing could be a huge source of revenue – the more distinctive a logo the better.

Competitors come and go

Berger’s buddy NFL Commissioner Bert Bell died in 1959 and it looks like all bets were off thereafter as to any NFL exclusive with Topps. Fleer entered the pro football market in 1960 by getting a license to produce AFL cards. Both Topps and Fleer had many of the same AFL and NFL players in their 1961 sets, with both manufacturers buying licenses from both leagues. Fleer card sales and production must not have been too snappy since their 1962 and 1963 AFL cards are scarce today. Post Cereal issued 200 NFL cards only in 1962, featuring players in imaginary action with no helmets or logos.

Philadelphia Gum entered the fray in 1964 and obtained an exclusive license to produce NFL cards that included team logos as well as the NFL logo, which was prominently displayed on each card. Topps replaced Fleer in producing AFL cards from 1964-67. The AFL didn’t have a players’ association until 1964, but at some point players’ associations for both the NFL and AFL got involved in licenses. In baseball by 1968, Marvin Miller was negotiating new group deals with Topps on behalf of the players’ association, more than doubling the income to the players.

Topps continued to show a few logos on their cards with a popular shot being a portrait of the player holding his helmet as if he were about to put it on and get into the action. There were still no real action photos other than a few game highlight shots in the 1960 set.

NFL license discontinued

In 1963, the NFL established an entity to handle licensing called NFL Properties. NFL Properties may have contributed to the switch to Philadelphia Gum, but Topps was back in a deal with the league for 1968 and 1969. The 1969 Topps set featured some 26 players with their helmets including logos. In early 1970, the NFL and AFL merged, as did their respective players’ associations.

In 1970 and continuing through 1981, Topps did not have a license agreement with the NFL to use logos. However, they did apparently obtain an agreement with the NFL Players Association in 1970 to show the players in uniform with numbers but without logos – the “players in their underwear” image described earlier. Consequently, players were either shown without helmets or logos were airbrushed off the helmets by an increasingly busy group of Topps artists. The Topps-drawn team logos morphed further into chubby, generic linemen in the 1971 set.

Logo litigation

The use of names, logos, symbols, emblems, designs and uniforms and all identifications, labels, insignia or indicia, as they say in the legalese, became fertile ground for suits involving players, teams, leagues, advertisers, equipment providers and sports card issuers in such exciting arguments as parasitic advertising, spatting and publicity rights. Lawyers got to discuss whether trademarks were generic, descriptive, suggestive, arbitrary or coined. Lawyers debated whether showing football players at work implied a license by the league when none existed. Even the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader outfits were covered in the litigation mix. Disputes involving the merger of the leagues, antitrust acts, player bargaining rights, salary caps and strikes added to the great opportunities that mushroomed in the field of sports litigation. The battles on the football field may have been easier than those in the court rooms. The book The Business of Sports, A Primer for Journalist by Mark Conrad is an excellent source of information to help understand the business and legal issues in all sports.

Getting the action photos

As cameras and lenses improved in the 1970s, Topps went for more game action photos in football, much in the same way action photos developed in baseball. Because the photographers were on the sidelines near the action, they could get candid portraits of players and action photos from the field. However, photographers had to deal with low camera angles and players between them and their subject. Jacobs recalled one stadium where benches for both teams were on one side of the field, which made it even harder for their photographers to wedge themselves in.

Jacobs recalled that it wasn’t all that easy just getting on the field. “The sidelines could be quite chaotic with not only team personnel, but reporters and even players’ families right along the sideline. Since Topps dealt with the players’ association rather than the league, our photographers had to get credentials to be on the field.”

In some cases, Topps used newspaper photographers who already had credentials. Jacobs mentioned, “Mickey Palmer was a Topps baseball photographer who also worked the football games.”

Another long-time Topps baseball photographer was Doug McWilliams, who shot football games in the early 1970s. He concurred that the sidelines were difficult. Photographers risked getting run over as they viewed the action through long lenses. McWilliams didn’t relish hearing “security people continuing to yell at you to kneel down.” He also told me, “You didn’t get to know the players like you could when you photographed the baseball players.” He decided to stick to baseball.

At least, the photos were taken during day games in outdoor stadiums, and photographers didn’t have to deal with challenges due to indoor or night lighting conditions.

Buckets of paint for airbrushing

Topps started with action photos in their 1971 set and kept at it. However, with all the non-licensed subjects on the field, the Topps airbrush artists got a real workout, and some of the results were humorous. Topps took care in eradicating anything that could be a potential problem. For example, Rams helmets were white with blue horns at the time. Topps artists whitewashed the blue horns and the helmets became all-white, looking more like cue balls. In picking photos to use, Jacobs had to consider the need for re-touching by people like Topps artist Norm Saunders. Jacobs recalled the 1978 card for Falcons center Jeff Van Note had to be retouched to get the blood off the bridge of his nose, which didn’t look too good. Dirty pants even got cleaned up.

Numbers and faces of referees and chain crew members had to be whited out or blurred into oblivion, as well as anyone else on the sideline who wasn’t a player and party to the Topps agreements. Even the “NFL” logo on the balls in the photos got airbrushed. Collector Marty Ohman acquired some of the unaltered Topps contact proofs which demonstrate the considerable airbrushing required to create the resulting action cards.

Fleer Corporation was able to issue game action cards starting in 1976 under an NFL license with the full use of logos; however, they couldn’t identify the players in the photos because they didn’t also have a license with the players’ association. Topps had the opposite problem. If you wanted players throughout the league with logos, you could drive around to Sun Oil gas stations in 1972 and accumulate 624 player stamps that were apparently licensed by the league and the players. That was about it. (There were exclusions in all sports allowing teams to issue team sets showing players and logos without sharing revenue with the rest of the league.) Finally in 1982, Topps paid the NFL (league) to use the logos and put the spray paint and funny logos away. Topps immediately utilized their newly acquired rights by featuring team helmets as the logo for each card, but it was a long time coming.

Rookies and even future HOFers wait their turn

The timing of photos created an additional challenge for football sets. Photographers would shoot baseball players in spring training of the year prior to creating a set. Spring training rosters included players who might not make it to the big leagues for another year or more. Even though Topps didn’t use a photo of a new player immediately, they would still usually have one handy for the next year.

Football rookies, though, were playing college ball in the year prior to appearing in the NFL; getting amateur college players and their schools involved in the rights to photos was problematic. The draft was held at about the same time that Topps worked up their sets for the coming year for sales between August and November. Topps photographers didn’t go to every training camp either, although they did travel extensively during the regular season, according to Jacobs. Even if the player was a first round draft choice, they usually didn’t get a card in their first year. Jacobs remembered that they would “look to photograph players in the skill positions plus any All-Pro linemen” but not every player. Jacobs said that Bill Haber was involved in deciding which players to feature in the set.

For example, in 1970 there were 26 NFL teams with 40 players per team totaling 1,040 active players. The 1970 Topps set had 263 cards, or fewer than 11 cards per team. Some star players, like linemen or lower round draft choices, waited a few years before they got a card. This was the case with 1979 third round pick Joe Montana, whose rookie card was in 1981, and HOFers Tom Mack and Alan Page, who started in the NFL in 1966 and 1967, respectively, but didn’t have cards until 1970. Players could also opt out of the players’ association group agreements and handle licensing on their own, although this didn’t make economic sense for most. Joe Namath and Earl Campbell were among the few who opted out and were absent from some sets.

Jacobs remembered, “Some players would just disappear on you. They might be injured and not even be with the team for a particular game . . . Careers were sometimes very short.”

The rookie exceptions

There were exceptions to this timing for some rookies. Paul Hornung won the Heisman following his 1956 season at Notre Dame, was drafted No. 1 in the NFL and was featured on his Topps rookie card in the 1957 set, his first year in the league. Ernie Davis was drafted following his senior year at Syracuse in 1961, but was diagnosed with leukemia in 1962. He had a 1962 Topps card but never played in the NFL and died in 1963. Other rookies who got a card their first year included Tommy McDonald, Jerry Tubbs, Roman Gabriel, John Huarte, Joe Namath, Fred Biletnikoff and Tony Dorsett. Jacobs said that starting in the late 1970s they would try to include Heisman Trophy winners and No. 1 draft choices as rookies in their sets.

Traded players and expansion teams

Baseball players would get their hats airbrushed or remain hatless, but football players were usually without helmets to start with and their jerseys looked fairly generic. They didn’t seem to get traded as often as baseball players either. When the Dallas Cowboys hastily re-entered the NFL in early 1960 to prevent an AFL team landing in Dallas, the Cowboys had no logos, helmets or players. Nonetheless the players drafted from an expansion pool were included in the 1960 Topps set in the motley uniforms of their prior teams. No airbrushing was attempted.

Lessons learned

When I look at football cards now, I check to see how logos and team names are handled. Sports card history can be challenging to recapture years later as to what happened and why. Advances in photography and printing made football cards progressively more dramatic, and NFL trademarks and team logos improved the look considerably. As Butch Jacobs said, careers are short in football. You want the players to look as good as possible.

George Vrechek is a freelance contributor to SCD and can be contacted at vrechek@ameritech.net.